![]()

Chapter 1

Urban prosperity without growth

The role of actors and social innovation

Thomas Sauer

1.1 Sustainability needs transition

Since the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, the concept of sustainable development has become more and more mainstream in global political thinking. The most prominent, and at the same time very general, definition of sustainable development was developed by the Brundtland Commission, formally known as the World Commission on Environment and Development (The World Commission on Environment and Development 1987). It considers sustainable development as development to meet present needs without compromising future generations’ ability to meet their own needs. The United Nations is currently preparing a ‘Post-2015 Agenda’, breaking down the overall idea into a set of measurable sustainable development goals for the period up to 2030 – succeeding the current Goals of the Millennium Declaration of 2000 (UN 2014a) and the Kyoto Protocol on reducing worldwide greenhouse gas emissions as well. Both are in urgent need of a binding follow-up.

Confronting the slow progress in realising past sustainability commitments, the question arises whether becoming mainstream will be enough to stop the ongoing human-inflicted contribution to global warming and loss of biodiversity. The answer to this question is probably negative. However, in the community of concerned scientists, a major paradigm shift is underway. It is a shift from the early ‘Limits to Growth’ debates of the 1970s, which were referring mostly to assumed trends of human overpopulation, towards a debate recognising the implications of core planetary boundaries (Johan Rockström et al. 2009). Their trespassing would cause an irreversible loss of human control capacities on the endangered global resource systems. If this trespassing is caused by humans, it is realistic that the geologic era of the Holocene already passed into a new period to be labelled as the Anthropocene (Jan Zalasiewicz et al. 2012). Considering the current geologic epoch as Anthropocene implies admitting the outstanding human responsibility for a resilient future of the earth system.

Since the early 1990s, economic sciences have debated on two main alternatives for optimal policies for the stabilisation of the climate processes: pricing the greenhouse gas emission via carbon taxes or constraining the eligible quantities of greenhouse gas emissions. The latter option presupposes that the markets would find the appropriate prices for the emission certificates, derived from such greenhouse gas emission control rates (William D. Nordhaus 1994). Both policy strategies are intended to internalise the “greatest externality ever” (Hans-Werner Sinn 2007) by giving greenhouse gas emissions a price in order to reduce the demand for it and to cover the social costs of such global overuse of the atmosphere. Despite some successes (Mikael S. Andersen 2010), only some of the EU countries introduced carbon taxes while the EU as a whole opted for an Emission Trading System, which is currently under reform after delivering some disappointing results in the first two phases (European Commission 2013b). Nevertheless, the problem appears more profound than simply choosing between two different ways of internalising the externalities of global market activities by international agreements or optimising emission trading schemes.

What if the United Nations takes the already agreed 2°C goals seriously as the limit for acceptable global warming in the twenty-first century? To meet this target, the world would have to reduce its CO2 emissions by at least 41 per cent up to 72 per cent in the four decades between 2010 and 2050 (IPCC 2014). Keeping in line with this goal would imply an annual reduction of CO2 emissions of at least 1.1 per cent in the world average until 2050. But, hoping this reduction could be led by a significant reduction of carbon energy intensity alone is misleading, as experience shows: The carbon intensity of economic growth, measured as CO2 emissions per $1 GDP, decreased by only 1.2 per cent per year as an average for the two decades from 1990 to 2010 (UN 2014a). Thus, by this strategy alone, the average country would have had a maximum eligible growth corridor of 0.1 per cent per year (1.2 per cent annual reduction of carbon intensity minus 1.1 per cent annual CO2 reduction). Given that this low average speed of carbon intensity reduction would be representative for all countries – and lasts until 2050 – there would be no room for GDP growth on the global scale.

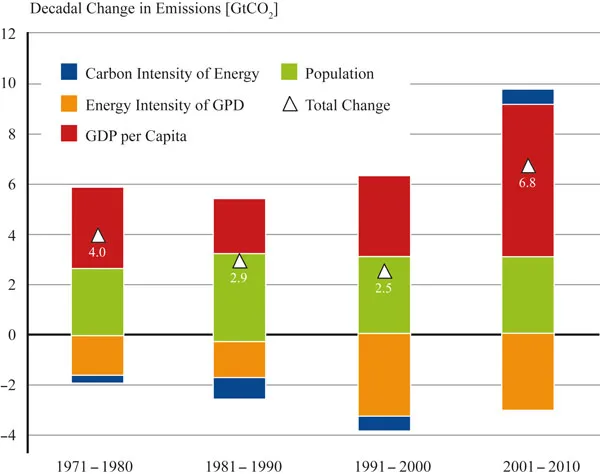

Figure 1-1 Decomposition of the change in total global CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion

Nevertheless, as Figure 1-1 reveals, the real development is even worse: The decreasing energy intensity of income per capita alone could have contributed significantly to the reduction of CO2 emissions over the last four decades – if neither world population nor world GDP had grown during the same time. Obviously, this was not the case: Growing world population induced a decadal CO2 emission increase of around 3 gigatons (Gt) of CO2 since the 1980s. Moreover, the CO2 emission growth induced by GDP growth per capita even accelerated, particularly in the first decade of the twenty-first century. In this time period, the high growth rates of world GDP coincided with an accelerated growth of world CO2 emissions up to a maximum of an additional 6.8 Gt and with a sudden increase of carbon intensity of energy after three decades of decrease. There is obviously no turnaround in the direction of shrinking global CO2 emissions in sight, despite the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and a series of high-ranking international climate conferences since the early 1990s.

A decoupling strategy, aimed at decreasing the energy intensity of GDP, is widely considered as the most helpful factor for a transition towards a climate-neutral regime. However, this kind of strategy delivers nowhere near enough reductions of greenhouse gases. The slowest factor for climate relief is probably population growth, because this variable entails long time lags and can hardly be influenced by demographic policies, at least in the time period available to stop global warming. Therefore, climate policies could focus on per capita income growth and the growth of carbon intensity of energy. However, the latter, carbon intensity, is probably a variable dependent on the former, the growth rates of GDP per capita. In the decade with the lowest growth rates of GDP (the 1980s), the most significant decline of carbon intensity was observed. In contrast, the extraordinarily high GDP per capita growth rates of the 2000s coincided with the strongest increase of carbon intensity in the same decade.

This is bad news for the hope that high GDP growth rates of the emerging markets in Asia and elsewhere would automatically induce a kind of ecological leapfrogging through the high investment rates of these countries. Despite the significant investments in renewable energy technologies, the proportion of investments in conventional fossil-fuel-consuming technologies appeared to be even higher there. Thus, the global GDP growth rate remains without doubt the critical variable for reducing emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases to a level consistent with the internationally agreed 2°C ceiling of global warming in the twenty-first century. The same is probably true as well for the overall planetary boundaries, like biodiversity loss, caused by human economic activities (Rockström et al. 2009). To conclude, market income growth, measured as GDP per capita, is the most severe risk for the resilience of key global resource systems.

A central question arises: Are the problems of global warming and of violating the overall planetary boundaries unsolvable social dilemmas in economic reality? Not at all, if the economic sciences would shift their focus from internalising the externalities towards the search for a more comprehensive economic approach regarding the governance of commons and the resilience of resource systems. The term socio-ecological transition (SET) concerns the shift of socio-ecological systems from one state to another. This implies that transitions are always directed towards something like a new equilibrium, a new regime, or a certain benchmark like ‘strong sustainability’. Thus, new institutional arrangements beyond the simple market–government dichotomy are needed to enhance human prosperity without overstretching earth’s capacities to recover. Such a transition towards a regime of strong sustainability presupposes the transition of the economic system towards a higher degree of institutional diversity. This would enable experiments with new forms of economic governance, which could be independent of the ever-growing consumption of natural resources.

Institutional diversification implies by definition, not only the emergence of new institutional arrangements, but the persistence of incumbent institutions as well. This raises the particularly important question of how an economy in transition towards a growth regime capable of safeguarding the resilience of ecological resource systems would affect the institutional settings constituting labour markets. They have to cope with any change in an economic and societal system that is induced by a socio-ecological transition. Since any governance mode, by policies or self-organisation, that relies on a reduction of CO2 or, in a broader sense, on a sustainable paradigm affects economic competitiveness, unemployment disparities are unequally hit by sustainability policies. A perspective has to be taken to make the efficiency of labour market policies visible and especially show how this institutional setting is altered and governed by policies. After all, all markets are dependent on coherent governmental intervention. Nonetheless, the perspective shifts from an overarching to a contextual one that differentiates structural features of the individual regions.

So there are strong reasons to look at such processes of institutional diversification and change, taking the multilevel character of governance of the global commons into account at the same time:

[W]hile many of the effects of climate change are global, the causes of climate change are the actions undertaken by the individuals, families, firms, and actors at a much smaller scale… . To solve climate change in the long run, the day-to-day activities of individuals, families, firms, communities, and governments at multiple levels – particularly those in the more developed world – will need to change substantially.

(Elinor Ostrom 2009, 4)

For research strategies regarding such social dilemmas, this entails a significant shift of perspective towards the behaviour of individuals and groups managing critical resource systems on a local scale.

For climate-neutral policies – as well as those regarding ecological resilience – the option to choose a bottom-up approach would skip any excuse for persistent inaction:

[C]ontinuing to wait may defeat the possibilities of significant adaptions and mitigations in time to prevent tragic disasters… . [W]ithout numerous innovative technological and institutional efforts at multiple scales, we may not even begin to learn which combined sets of actions are the most effective in reducing the long-term threat of massive climate change.

(Ostrom 2009, 4)

Thus, for solving social dilemmas at the global level, it is crucial to understand and to change the determinants of human economic behaviour at the local level in its relation to the socio-ecological context first. Local cooperation produces a wide variety of social innovations that are adapted to the local context they concern (Geoff Mulgan et al. 2007; James A. Phills, Jr., Kriss Deiglmeier, and Dale T. Miller 2008; Hans-Werner Franz, Josef Hochgerner, and Jürgen Howaldt 2012; Andreas Reinstaller 2013; Harald A. Mieg and Klaus Töpfer 2013). “Social innovations are new solutions (products, services, models, markets, processes etc.) that simultaneously meet a social need (more effectively than existing solutions) and lead to new or improved capabilities and relationships and better use of assets and resources” (Anna Davies and Julie Simon 2013, 5). This book focusses on social innovations in three urban resource systems (energy, green spaces, and water), as well as regarding the local labour markets of 40 European cities.

1.2 New seeds of sustainable prosperity

At the very heart of our understanding of whether our market-based economies have to grow, notwithstanding the resilience of ecological resource systems, is the concept of capital. It entails a range of important questions, such as: Is it sensible to assume a general ability to substitute natural capital by human-made capital, or is such substitutability constrained by planetary boundaries as sketched above? Is economic capital by definition forced to grow – as it is expressed with the concept of capital accumulation? Moreover, what is actually assumed as growing when economists are talking about capital accumulation?

The latter question was already put by Gabriel de Tarde in his “Psychologie économique” of 1902:

In my view, there are two elements to be distinguished in the notion of capital: first, essential, necessary capital: that is, all of the ruling inventions, the primary sources of all current wealth; second, auxiliary, more or less useful capital: the products which, born from these inventions, help, through the means of these new services, to create other products. These two elements are different in more or less the same way as, in a plant seed, the germ is different from those little supplies of nutrients which envelope it and which we call cotyledons. Cotyledons are not indispensable; there are plants that reproduce without them. They are very useful. The difficulty is not in noticing them, when the seed is opened, for they are relatively large. The tiny germ is hidden by them.

(Tarde 1902, 229, as translated in Bruno Latour and

Vincent A. Lépinay 2009, 49–50)

Tarde defines necessary capital as the capability to innovate processes as well as products – already before Joseph A. Schumpeter published his “Theory of Economic Development” in 1911. Like a germ, it is the source of all current wealth. In contrast to that, Tarde compares auxiliary capital with cotyledons: These are useful suppliers of nutrients for seeds, but they are not necessary to reproduce these seeds. Because cotyledons are relatively large compared to germs, the germs are often hidden by them. This metaphor ends up in a comparison between economists and botanists: “The economists who saw capital as solely in the saving and accumulation of earlier products are like botanists who would view a seed as being entirely made up of cotyledons” (Tarde 1902, 229, as translated in Latour and Lépinay 2009, 50).

As in the days of Tarde, most of the economists today are still focusing on the ‘more of the same’ concept of capital as the wealth-enhancing approach, still mixing up the saving and accumulation of earlier products with real generation of wealth. In contrast to that, a modern concept of capital should start with Tarde’s idea of emphasising the capability to innovate and to learn as its core characteristics and to discard income growth as its key property. This could free the mind of economists and enable them to search for new institutional arrangements.

What is needed is an economic system that would be able to cope with growth rates of market income, which are safeguarding the resilience of local ecological resource systems as well as the global ecological system within their planetary boundaries. It is obvious that there exist neither ready-made blueprints nor panaceas for such a sustainable economic system. If anything, market income growth appears to be deeply entrenched in the contemporary market-based economies. Thomas Piketty (2014) observes a strong long-term tendency for the rate of return on capital to be even greater than the rate of overall economic growth. This is feasible only at the cost of labour income and results in a concentration of wealth – as well as of economic and political power – in the hands of a few. Otherwise, modern welfare states are heavily dependent on taxing value-added and market incomes for financing their comprehensive tasks in stabilising the economy and for compensating the majority of the electorate for the most severe consequences of the unequal distribution of wealth and income. Finally, yet importantly, modern labour markets are dependent on economic growth for keeping employment rates stable or even increasing them. Thus, this profound entrenchment of the pursuit for economic growth in the institutional setting of current market economies is not easily resolved. However, there appears to be no other way to keep human development inside the crash barriers of planetary boundaries. This affects labour market policies as well, following the argument in this section. Instead of widespread distribution of employment, labour markets as institutions pronounce the more locally rooted microbalance of social inequality in the form of unemployment disparities.

Therefore, we face the task of finding new institutional arrangements ensuring human well-being and the resilience of ecological resource systems at the same time. For labour markets, the task is very similar: Instead of finding distinctive new institutional settings, it is urgent to find structural improvements to the existing exchange mechanisms. This means that policies need to be analysed, and it needs to be scrutinised which goals are necessary for the altering of functions. Thus, the question arises of where to find such new institutional arrangements – which would follow a strategy generating prosperity without growth (Peter A. Victor 2008; Tim Jackson 2009) or “Green Agrowth” (Jeroen van den Bergh and Giorgios Kallis 2012; Jeroen van den Bergh 2015). It is extremely likely that neither the profit-driven business sector nor the tax-revenue-dependent government sector would emerge as home of such growth-ignoring new institutions, even if it were possible to shift governance revenues towards a more tax-independent financing by profits of state and priva...