![]() Part 1

Part 1

Context and principles![]()

1

Pedagogy Development

Transmissive and participatory pedagogies for mass schooling

João Formosinho and Júlia Formosinho

The first level of education to become compulsory for all children was primary school education, beginning with five-to six-year-old children. It was then extended to the lower secondary school and, finally, compulsory secondary schooling was considered necessary for the education of children and adolescents eventually up to 18 years currently in most Western societies. More recently, mass schooling has been progressively extended to include pre-primary early years in mainstream education. Within Europe, this can mean that children from birth through to six years can find themselves in centre-based, out of home, education and care with compulsory attendance at four, five, six or seven years being dependent on the individual policies of different nations.

Chapter 1 of this book deconstructs the continuing pervasiveness of transmissive pedagogy used in most mass schooling which has constituted mainstream education in the twentieth century and asserts its inappropriateness for early childhood. Since early childhood education is progressively joining in mainstream provision, we call attention to the risks of this inclusion hoping to contribute to the preservation of the spirit of educational freedom always present in early childhood settings.1

The first section of this chapter expresses how the scientific ‘management of education’ prevailed in the building up of mass schooling during the twentieth century. Although John Dewey’s ideas considering the school as a place to learn how to live and to build democracy developed exactly at the same time as Ford and Taylor’s organisational ideas for industrial production, these latter were the ones which prevailed in educational expansion. This expansion of an education initially designed only for an elite to compulsory and universal entitlement was done with reference more to the dominant organisational theories of the industrial revolution than to pedagogical ones. Our analysis of the building of this segmented and compartmentalised mainstream education in the twentieth century underpins this chapter (Formosinho and Machado, 2007, 2012).

The second section of this chapter affirms that there are, and always have been, participatory alternatives to this mainstream pedagogy, even from the very start of mass schooling expansion. Two authors, especially, opened possible worlds for child hood pedagogy: John Dewey and Paulo Freire. These two pedagogues when considered in dialogue with each other help us to understand other possibilities, to develop the will to undertake change and to create networks of praxis that are respectful of the key actors of pedagogic development: children, educators and families.

To further help to create these networks of participatory praxis, the third section of this chapter aims to characterise the essential differences between these two basic perspectives, transmissive and participatory, explaining their respective rationale. Behind these two different approaches are different visions of teaching, learning and education. The aim of this section is to present these essential differences related to values and worldviews, goals and objectives, methods and operational principles, the organisation of knowledge and the organisation of curriculum, the role and image of teacher and learner, and the respective conception of assessment and evaluation. It is also our intention in this section to explain why the mainstream educational process is generally based on transmissive pedagogies.

The final section of the chapter analyses how the growing inclusion of early childhood education and care in compulsory education may tend to include it in the mainstream delivery mode, promoting the attendance of early childhood mainly as preparation for primary school. It would be contradictory and unethical that the growing acknowledgement of the importance of early childhood education in children’s learning should promote the very characteristics which would limit its benefits.

The segmentation of education in the development of mass schooling

The ‘scientific management of education’: the contribution of Taylor and Ford

Traditional education aims to transmit to a next generation those skills, facts and standards of moral and social conduct that adults consider being necessary for the next generation’s material and social success (Dewey, 1938). This transmission is often based on memorisation, rote learning (memorisation with no effort at understanding the meaning). The students are expected to obediently receive and believe these fixed answers; teachers are the instruments by which this knowledge is communicated. The main proposals of the progressive education movement, active since the last decades of the nineteenth century, were quite the opposite. They include an emphasis on learning by doing rather transmission, the selection of subject content based on the future needs of society rather than on internal academic continuity, an integrated curriculum focused on thematic units rather than a curriculum based on segmented knowledge, a pedagogy based on problem solving and critical thinking rather than aiming at rote learning, and based on group work and cooperation rather than promoting competition. And, finally, an assessment by evaluation of each child’s projects and productions, rather than assessment of task completion or using tick box questionnaires.

John Dewey (1859–1952), one of the leading members of the progressive movement,2 Frederick Taylor (1856–1915) and Henry Ford (1863–1947), the most influential proponents of the scientific management of industry and economy, were contemporaries and developed their main ideas and theoretical constructions in the last years of the nineteenth century and the first years of the twentieth century. The worldview and conception of humanity underpinning the progressive education movement and the scientific management theories were quite opposite. But the import to education of the industrialised organisational theories, that is, the ‘scientific management of education’, appeared to most Western governments as a more efficient tool for the development of mass education as it was already an indispensable mechanism for mass production in industry.

Taylor’s theory of management aimed to transform craft production into mass production, improving efficiency, standardising the best practices. The agents of execution need not be ‘smart’ to execute their tasks. Ford’s contribution was the development of an important mechanism for the standardisation of mass production through the breaking down of complex tasks into simpler ones, with the assembly line workers being merely executors of these simplified tasks.3 On the assembly line, the manufacturing process is comprised of incremental different parts added in sequence as the semi-finished assembly moves from work station to work station until the final assembly is produced.

Thus the development of public school for all in Western societies seems to be, in the organisational dimension of schooling, more in debt to Taylor, Ford and Weber4 than to Froebel, Montessori, Dewey, Steiner and other progressive pedagogues. For the educational mass production system to be efficient it was necessary to modernise the nineteenth century traditional education; the ‘scientific management of education’ appeared to serve more efficiently the traditional education aims through the standardisation of the content and the means (curriculum and pedagogy), thus maximising mass production of schooling. This standardisation demanded a single, unified curriculum for all students, regardless of motivation, developmental level or interest. It required that all students be taught the same materials at the same time and at the same rate. In order to achieve this, teaching groups should be homogeneous, with students matched by age and by ability; students that did not learn quickly enough failed, rather than being allowed to succeed at their natural speeds. The evaluation of students as control of knowledge acquisition was done through tests and final examinations.

The set up of the ‘educational assembly line’

The standardisation of the content was obtained through the breaking down of the knowledge into different specific subject units (horizontal segmentation of the curriculum), dividing each subject unit into school grades (vertical segmentation of the curriculum) and organising the curriculum through assembling these subject graded units into sequent school grades. The organisation of the teaching schedule for each week, month or school year is based on the same principles since it accommodates and organises both types of segmentation based on temporal teaching time units (typically the hour).

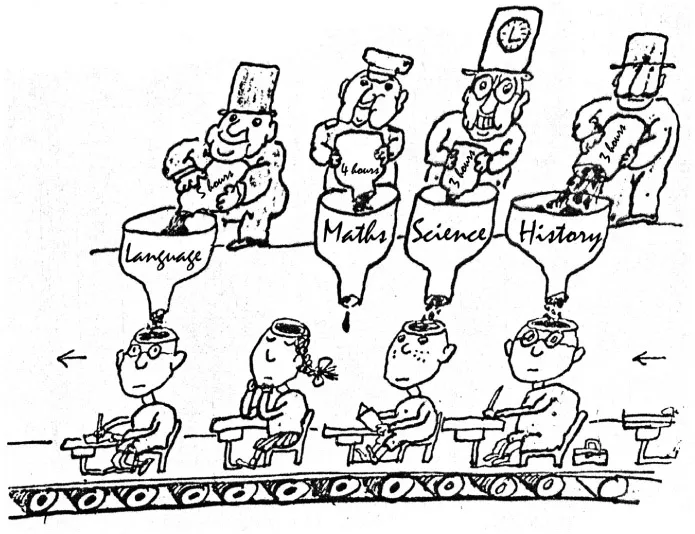

Figure 1.1 The ‘modern scientific management’ of schooling to maximise mass production of education

Students flow throughout the day according to these temporal teaching time units from one subject teaching unit to another, thus building, day by day and year by year, the educational assembly line.5

The ‘bureaucratic management of education’: the contribution of Weber

The State developed a bureaucratic model for the performance of its educational mission. Thus Weber is added to Taylor and Ford as an important contributor to the development of mass education.

In countries with administrative traditions based on centralisation, the State has conceived a unique way of ensuring the universality of education and, hence, of defining an optimum pedagogy which is set out in a school curriculum. When defining this curriculum, the central educational administration determines in uniform fashion for all the national territory and for all students what they should learn and, hence, what should be taught, while explicitly or implicitly assuming basic standards as regards educational conceptions and purposes. The definition of the curricular corpus is integrated into a conception of the school as a social place for formal education and social control, which has lent it legitimacy during the course of modernity and made it into an ideological apparatus of the State. At the same time, it incorporates conceptions and guidelines about the mode of structuring and materialising the curriculum as regards contents, methodologies and assessment.

The centralised bureaucratic model for formulating the curriculum cultivates uniformity and revolves around an abstract ‘average’ student. The role of each subject matter in the curriculum, the weekly workload and the programmatic contents are defined at a higher level. General methodological guidelines are formulated, with the purpose of recommending the best methods and techniques for transmitting the predefined curriculum contents in presumably uniform settings.

This led to a ‘bureaucratic pedagogy’ at both curriculum and classroom levels and uniformity in classroom practice was induced by strong normative control on all details of school management, while curriculum and pedagogical solutions were planned for the ‘average able student’ taught by the ‘average teacher’ in the ‘average school’. This ‘average able student’ was the conforming, knowledgeable and motivated student. Curriculum remained uniform for all students and schools, regardless of previous learning experiences, of diverse capacities and motivations, of different interests and expectations. This ‘ready to wear single size curriculum’ (Formosinho, 1987, 2007) produced for all schools the same number of lecturing hours per subject, using the same syllabus, in the same teaching units, all determined by norms at central level. This ‘one-size-fits-all curriculum’ was taught to all students, regardless of their learning, ability, motivation, interests or expectations; in all classrooms, regardless of level of tracking; and, at all schools, regardless of the population and characteristics of the communities they served.

To teach the same content to all children at the same time in the same manner was seen not only as the most rational and ‘scientific’ mode but also the embodiment of educational equality of opportunity. This ideal was a blend of an ideological concept of equality seen as uniform treatment for all and of the centralised bureaucratic tradition of governing the educational system. This blend of bureaucratic reason and ‘egalitarian’ values is embodied in a conception of equality as uniformity, that equality of opportunity means the same treatment for all, regardless of their different competencies, interests, needs or learning progress.

The organisational and pedagogical instrument used to transform the teaching of several students into the teaching of the single abstra...