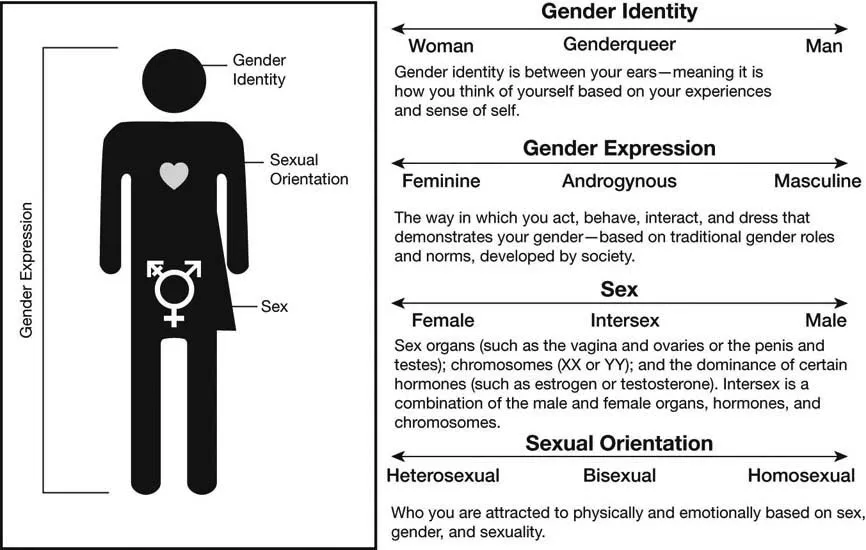

Was the situation that led to Anthony Wiener’s resignation from the U.S. House of Representatives about sex? The answer to that question depends, in part, on what the term means. Yet, for reasons that this chapter should make clear, it is difficult to craft a straightforward definition of the word sex because its range of meanings refers to a continuum of behaviors. And, as Figure 1.1 illustrates, gender and sexuality are similarly complicated concepts.

Sex

Sex refers to both biological characteristics, as well as certain acts through which we express desire or release sexual tension (Richardson, Smith, & Werndly, 2013).

Biological sex. When sex is used to refer to biology, we tend to think of humans as being male or female, depending on chromosomal expression (e.g., XY for males; XX for female); internal reproductive organs (e.g., the presence of ovaries, fallopian tubes, and a uterus in females; the presence of a prostate and testes in males); and external genitalia (e.g., a penis and scrotum for males; a vagina for females).

The male/female binary for sex is mis leading because humans can be intersexed—a term referring to “medical conditions in which the development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomic sex varies from normal and may be incongruent with each other” and, therefore, who do not fit the usual definitions of male or female (Allen, 2009, p. 25). For example, individuals whose 23rd pair of chromosomes (the sex chromosomes) are XXY occur in roughly one out of every 500 to 1,000 births (Colapinto, 2000; Wattendorf & Muenke, 2005). A small penis, small testes, low androgen secretion, and possible female breast development are characteristics of this chromosomal karyotype that is known as Klinefelter Syndrome (Wattendorf & Muenke, 2005). People with this condition typically live as men.

Figure 1.1 The continua of sex, gender, and sexuality expression

Intersexed individuals were once referred to as hermaphrodites based on the Greek god Hermaphroditus who was both male and female (Gurney, 2007). Today, there are at least 17 different intersex conditions, but most intersex individuals are classified as being either true hermaphrodites or pseudohermaphrodites. True hermaphrodites are rare; they possess both ovarian and testicular tissue, whereas pseudo-hermaphrodites occur more commonly—1 in 2,000 births (Colapinto, 2000)—and these individuals possess ambiguous internal and external reproductive organs, but do possess the genitals of their dominant sex (Gurney, 2007). Research has suggested that while being intersexed is a result of biological outcomes, possessing ambiguous sexual anatomy is not a medical issue in most cases and medical interventions are not required (Preves, 2013). Social stigmas and familial pressure to categorize children into gender binaries typically drive normalizing surgeries that are conducted to remove or “correct” the body. Duality is feared and, therefore, parents feel a pressure to ensure that their child’s gender and sex are as visually defined as possible (Preves, 2013).

Sex as a behavior. As previously mentioned, the word sex is not limited to biology; it also refers to behaviors. But this use of the word can be ambiguous (Sanders & Reinisch, 1999). Which acts qualify as “sex”? “For centuries, societies around the world adopted the view that sex means just one thing: penis-in-vagina intercourse within the context of marriage for the purpose of procreation” (Lehmiller, 2014, p. 2). Today, however, it is clear that sex—even when narrowly confined to the definition of penis-in-vagina intercourse—is no longer limited to the purpose of procreation within marriage. Regardless of the participants’ marital status, penis-in-vagina intercourse offers pleasure, connection to others, expressions of love, exploration, and, for some, even the potential to earn money. Moreover, what is now classified as sex is not limited to penis-in-vagina intercourse. Indeed, the terms oral sex and anal sex specifically refer to sexual acts other than a vaginal penetration by a penis. And ponder whether penetration is even necessary for sex; if two people engage in mutual masturbation, is that sex?

Gender

People often use the words sex and gender interchangeably even though the terms have distinctive meanings. Unlike sex, which—at least in the biological context, tends to refer to a reductionist male/female binary, gender is a socially constructed category that reflects a set of behaviors, markers, and expectations associated with a person’s biological sex and social norms concerning masculinity and femininity. A person’s gender is usually represented in three ways (Parent, DeBlaere, & Moradi, 2013). The first is associated with physical appearance vis-à-vis secondary sex characteristics, such as the presence or absence of an Adam’s apple, facial hair, the pitch of one’s voice, and the like. The second concerns gender identity—how someone identifies in selecting a gender. And the third concerns gender expression—how people present themselves to others in their appearance, behaviors, actions, and interactions.

The first representation of gender is, in large part, a function of biology. For instance, one is either born with or without an Adam’s apple. But other secondary sex characteristics are more malleable. Hormone therapy, for example, can alter the appearance of facial or body hair. The other two aspects of gender, however, are much more a function of the psychological and the social, both of which, to varying degrees, are partially dependent on social norms known as gender roles.

Gender roles are the behavioral, economic, and social roles that every society deems appropriate for members depending on their sex (Butler, 1999). Gender roles reflect societal norms concerning masculinity and femininity.

Social norms are societal rules. The norms that tell us what we ought to do—become educated; respect our elders; obey the law— are called prescriptive norms. The norms that tell us what we ought not to do—commit crimes, lie, drop out of high school—are called proscriptive norms (Anderson & Dunning, 2014).

Norms are based upon widely shared values regarding that which is “good” or “correct,” and, conversely, that which is “bad” or “incorrect.” Norms may be formal or informal. Formal norms, also known as mores, tend to have moral underpinnings. The values expressed in the Ten Commandments (e.g., not killing, stealing, committing adultery, etc.) or other religious doctrines, are examples of mores. In contrast, informal norms, also known as folkways, do not have as strong a moral foundation, but are social expectations nonetheless. Folkways include rules governing etiquette and acceptable standards of behavior, like how to dress for a particular occasion.

Norms vary across both situation and time. For example, language that may routinely be used while hanging out with your friends after school may be inappropriate to use at home with your family. Similarly, behaviors that may be considered perfectly acceptable by today’s standards, such as teenage males wearing earrings, would have been taboo, or unacceptable, to many of our grandparents or great-grandparents.

Norms also vary across cultures. For example, belching at the dinner table is considered rude in many Western cultures, but is considered to be a compliment to the host or cook in some African and Asian countries.

(Owen et al., 2015, pp. 101–102)

Children learn gender roles as they grow up by watching and interacting with the world around them (Adler, Kless, & Adler, 1992). Traditional gender roles reflect congruence between biological sex and gendered behaviors that separate characteristics of men and women as aligned with their male or female biology. These traditional gender roles are the norms that families pass along to children. This can even occur before birth; consider, for example, that upon learning “It’s a girl,” parents may paint a room pink and adorn it with toys (e.g., certain types of dolls) and images (e.g., princesses) associated with femininity in little girls. These gender roles are reinforced by family, friends, school, media, and society-at-large. But those gender roles may not align with how one comes to perceive one’s own gender because, unlike sex, gender is a psychological and sociological concept, not a biological one. A person’s biological sex may lead to an assumption of gender, but that same person’s gender identity may not reflect the biological sex assigned at birth. As one researcher stated, “Gender is between your ears and not between your legs” (Lehmiller, 2014, p. 116).

Gender identity is how one perceives oneself based on one’s experiences and sense of self (Lehmiller, 2014). One’s gender identity may or may not align with one’s gender expression—how an individual expresses gender through dress, behavior, mannerisms, and actions. As with biological sex, gender identity and expression do not fit into binary classification systems.

Gender and sex commonly align such that a person who is assigned female at birth perceives her own gender identity as being a woman and, conversely a person who is assigned male at birth perceives his own gender identity as being a man. Cisgender describes people who identify as and express the same gender they were assigned at birth based upon their perceived biological sex (Stryker, 2008).

Transgender, on the other hand, is a broad term used to refer to anyone who does not identify with or express gender norms that fit into traditional gender roles (Lehmiller, 2014; Stryker 2008). Transgender incorporates a range of identities, all of which do not conform to traditional gender expectations and presentations. Trans* has been used to represent the numerous identities that fit under the umbrella of being transgender. Trans* as a term does not stand alone, but may be used to describe a transgender person or identity. Trans sexuals, cross-dressers, and genderqueer all fall under that category of transgend...