- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Designbuild Education

About this book

Designbuild Education adopts the intellectual framework of American Pragmatism, which is a theory of action, to investigate architects' compelling urge to build and how that manifests in collegiate designbuild programs. Organized into four themes—people, poetics, process, and practice—the book brings together new essays by some of today's most well-known designbuild educators, including Andrew Freear from Rural Studio and Dan Rockhill from Studio 804, to shed light on the theoretical dimensions of their practice and work. Illustrated with over 100 black and white images.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Architecture GeneralPart 1

People

Community Engagement and the Common Good

1

Backyard Architecture

Andrew Freear

Deep Local

Backyard architecture is about being deeply and inextricably immersed in a particular place at a particular time. It is about understanding the ad hoc circumstances of a community and its people. It is about building trust. Backyard architecture is resourceful, opportunistic, and inventive by necessity. For Rural Studio, establishing roots and growing alongside our community was never a conscious act or strategic decision; for Rural Studio founders Samuel Mockbee and D. K. Ruth, it was bred-in-the-bone. And it has remained with us, and a part of us, throughout these past twenty-two years. By working in your own backyard, you cultivate relationships. You become a neighbor. People in the community begin to understand what you have to offer, and you begin to understand what they offer in return. Folks know that they can come to us, not just for help, but also for advice. They respect what we have done and what we continue to do. That is a big deal to us. Our community trusts that we are not going anywhere, that we will not abandon them.

It seems that architects in the pursuit of doing good look far afield for problems to solve—housing shortages, impoverished communities, lack of access to healthy food, starving children, scarcity of water, and resource depletion—all in places they know little about. Yet often the most difficult problems are in our own backyards. Rural Studio has never been about fly-off humanitarianism or architectural imperialism. Here in Hale County, I have had the opportunity to forge relationships with people I trust. By listening, we learn how we might be able to help just a little bit (it is always just a little bit). Of course it was not always this way. When I came to Hale County, I was met with deep suspicion, in part because they assumed I was another professor coming out here to conduct my research, receive tenure, and disappear. It is easy to understand that kind of skepticism. Rural Studio has stayed.

Rural Studio students are immersed in their new community. They are thrust out of the ivory tower of academia (Newbern, Alabama, the home of Rural Studio, is 150 miles from Auburn University, to which it belongs). They tutor at the local middle school, they work local jobs, they go to local churches, they dine out locally, and they play on local sports teams. They do this as individuals, as fellow members of the community, even if only for two or three years. They build relationships that last a lifetime.

The act of designing and making a building is such an optimistic, provocative act that people are naturally curious. I think that for our community, seeing young people go to extraordinary lengths and seeing them labor so hard earns a lot of respect. Locals are very proud that Rural Studio is in their midst. Even so, students routinely have chance encounters with members of the community, where they may be asked: “What the hell are you doing?” “Why are you doing this?” “Why is it this color?” The students become accustomed to these interactions. Living and working in a small town can be trying, but it can also be uplifting and immensely gratifying, particularly when the community comes together with the Studio and, all of a sudden, there is this incredible barn raising. The ups and downs are all part of life in a small town, lessons that are collateral effects of the designbuild pedagogy.

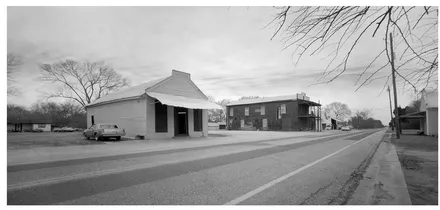

FIGURE 1.1 Downtown Newbern, from left, storage barn, Red Barn (Rural Studio’s design studio), post office, and Newbern Mercantile, Newbern, Alabama Source: Tim Hursley

Former Greensboro City Councilman Steve Gentry wished all small towns had a group of architects like Rural Studio. What he appreciated most was that he could “bend our ear,” not necessarily to commission a project, but just to ask our advice or run an idea by us at a conceptual level. The mayor comes to us when he has questions of an architectural or engineering nature. Community leaders recognize that my students and I have good intentions for the town of Newbern. In some respects, Rural Studio has become the town architect. The real-life immersion of Rural Studio has set up the conditions in which the Studio has been able to assume this mantle. Our designbuild pedagogy, particularly in an impoverished community such as ours, empowers the Studio to create real and lasting change, and that has been key to developing our relationship with the community. The opportunistic and resourceful designs of Rural Studio often employ unorthodox materials and approaches, requiring the designbuilder’s synthetic skills to pull them off.

The old adage about teaching a man to fish is really about the difference between enabling and empowering. A common criticism of designbuild programs is that they rely on donations, goodwill, and the free labor of students and—in the process of fulfilling their pedagogical mission—unfairly compete with professional architects and contractors. We at Rural Studio share this concern. I am diligent in making sure that none of these projects would happen without our collaboration. I am careful not to take food off the table of architects or contractors. Most of the time what we do contributes to the health of the local economy by creating opportunities where none previously existed. We hire local contractors to build parts of the projects that I deem are not academic. We collaborate with an architect of record. We work with our community partners to build skills that will empower them far beyond the fruits of our collaboration.

In the increasingly globalized world we live in today, where the creative nuclei of cultures are homogenizing at a sub-mediocre level and people are increasingly blinded by technology, place-based design is more important than ever. 1 Architecture is not just about making beautiful buildings; it is a dialogue with a place, its people, and a moment in time. The questions are essentially the same everywhere, but the answers must relate to place. It is a question of responsibility to the local culture and character. We build with what we have at hand. A house in Hale County ought to be different than a house in Chicago. Here the antebellum homes all have deep overhanging roofs. Tall ceilings and ample natural ventilation eases the discomfort of the hot, humid, stale air. The homes are raised off the ground, with generously shaded porches. These characteristics have survived for over 150 years, standing the test of time. A place-based design philosophy runs deep in the Studio; we believe people and place matter. When we work in our own backyards, we learn from the place. We learn from our mistakes. Since most of our projects are in a twenty-five mile radius, we naturally develop a healthy feedback loop with the community. If I design a building in Shanghai, how do I know whether the project was worth a damn?

Living with Your Mistakes

One of Rural Studio’s strengths has been that design has always been a priority. We are a design school. While our dedication to serving our community is far from incidental, nurturing young designers and giving them an opportunity to prove themselves is central to our mission. We do not think of ourselves as do-gooders or humanitarians. We are not here to dig ditches. We strive to do the right thing, to figure out what it means to do the right thing in any given situation. It is never a question of what can we do, but rather what should we do. Our students get rebuked a lot about the vocabulary they use. They often say “our project,” and when they do, my head immediately goes up. Nothing we do is possible without our community partners. There are, of course, programs that are more socially oriented than Rural Studio. There are programs that are more design-oriented as well. Rural Studio strives to balance these two values.

The academic year at Rural Studio is inaugurated with a rigorous and frank tour of completed Rural Studio projects. We discuss the aims and aspirations of each, and the gloves come off. Living with our mistakes means both acknowledging and accepting that we could do better and that the imbedded nature of the Studio allows us the opportunity to literally live with and learn from these mistakes when they occur. With somewhere between 150 and 200 projects in Hale County, we have great success stories as well as projects that have not lived up to their promise. Some of the latter have moved on from their intended purpose, as sometimes happens with buildings. With the community projects, their success is largely dependent on whether the doors are still open or not. And since we are here for the long haul, if we have made a mistake on a project, particularly one of our community projects, we hear about it. If there are maintenance issues, we are committed to chaperoning these projects into the future. It is important for our project teams to work closely with their community partners to ensure that there is a sufficient structure in place for the project to move forward and to sustain itself into the future. The Boys and Girls Club in Greensboro is a great example of the designbuild team guiding our community partners through the process. The team sat down with the nascent unit board, a group of folks interested in the idea of a Boys and Girls Club, and walked them through precedents from across the United States on how to go about establishing one.

Rural Studio Laid Bare

One of the greatest challenges of the designbuild approach, particularly with the socially motivated designbuild project, is honoring the fundamental pedagogical mission while fulfilling the promise to the community. There are moments when these two lofty goals can be at odds.

We, at Rural Studio, are disciplined in how we structure our projects to minimize future complications. Fifth-year students enrolled in Rural Studio spend nine months working with the community, developing their designs, and proving the concept through a series of stress tests, often including a full-scale mockup of the most challenging or structurally complex piece of the project. This stress test, in some respects, has become a rite of passage to proceed. Some students fail at that moment, others succeed. Still others get half way there and are given the opportunity to keep going because we trust they can pull through. Once they prove themselves, we give them the green light and at about this moment they formally graduate from architecture school. Then the building process begins, and this can take upwards of an additional two-and-half years. I have always been very proud of the fact that our students build these projects basically as volunteers; they do this because it is the right thing to do. Our students share the ethical convictions of Rural Studio. The bond between them, our community partners, and the Studio is stronger than the external pressures they face to move on. They are proof that, given an opportunity, twenty-two or twenty-three year olds are capable of extraordinary things.

FIGURE 1.2 Students testing eight-by-eight-inch cypress timbers comprising the entrance-door beam, Newbern T own Hall, Newbern, Alabama, 2011 Source: Andrew Freear

Cultivating relationships with the community is essential to what we do in Hale County. We build trust, and we are careful not to betray that trust. So when a student joins Rural Studio, they understand the commitments the Studio/we have made on their behalf. The key to Rural Studio’s success is that failure is always an option; only we do our best to isolate the tremors of failure before they impact the community. If we, as a studio, do not feel that a student has reciprocated that commitment, or if they have not proven themselves capable of moving forward, or if the students are capable but their proposal is ultimately not the right solution, we go no further. That is the deal. We are not afraid to determine that a project has not reached the right moment to move forward. To build is not a predetermined outcome. It is a privilege that is earned. If the project does not meet our internal expectations or those of the community, it does not go ahead. I...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Authors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Hands On, Minds On: Motivations of the Designbuild Educator

- PART 1 People: Community Engagement and the Common Good

- PART 2 Poetics: Experience and the Human Condition

- PART 3 Process: Methodology and the Tectonic Imagination

- PART 4 Practice: The Academic-Professional Bridge

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Designbuild Education by Chad Kraus in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.