eBook - ePub

Eastern and Southern Africa

Development Challenges in a volatile region

This is a test

- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Eastern and Southern Africa

Development Challenges in a volatile region

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A unique and comprehensive introduction to contemporary development issues in East and Southern Africa, and represents a significant departure from the often descriptive approach adopted by existing regional and development texts on African regions. Each contribution is carefully chosen to highlight the theoretical basis to development issues, and the practical problems of implementing development plans, in this vital subregion. Overall this produces comprehensive and balanced coverage of historical, economic, political and social issues. The twin issues of globalisation and modernisation give the book a clear focus.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Eastern and Southern Africa by Debby Potts,T.A.S. Bowyer-Bower in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER 1

Development challenges and debates in eastern and southern Africa

Introduction

The decision to produce a new series of regional volumes for the Developing Areas Research Group of the Royal Geographical Society/Institute of British Geographers was based on the view that the ‘dramatic changes in the global political economy, in the nature of development challenges facing individual developing countries, and in debates on development theory’ (Simon 1999a: xii) required a re-evaluation of major world regions from a geographical perspective. This volume covers the vast region of eastern and southern Africa – and there can be no doubt that the 1990s and the turn of the century have wrought major transformations in this region in terms of all three issues identified in the quotation above. A specific regional perspective on each of these issues is provided in this introductory chapter, thereby linking these themes from the global to the national and local level in the region. First, it is necessary to examine the interactions and factors which give this country grouping a degree of coherence, and then to discuss the developmental characteristics of the region.

Eastern and southern Africa: defining a diverse region

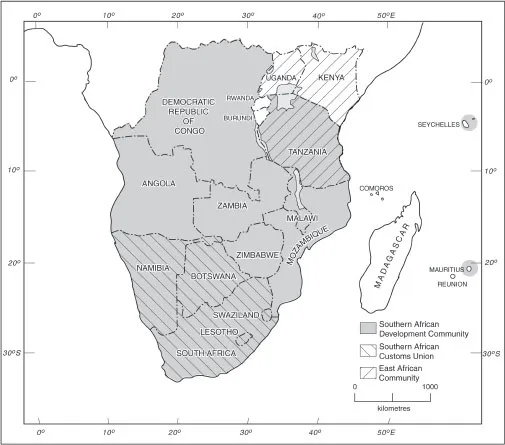

Defining regions within sub-Saharan Africa which lend themselves to critical analysis is no easy task. Different themes or disciplinary perspectives may logically choose somewhat varying regional boundaries. The geographical distribution of fundamental characteristics (be they environmental, historical, cultural, political or economic) rarely displays easy, definite patterns. Indeed, within sub-Saharan Africa, as Chapter 9 in this volume cogently argues, national boundaries themselves are exceedingly arbitrary (and are themselves a constraint on development). The region upon which this volume is based, eastern and southern Africa, covers 16 countries: South Africa; Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland and Namibia; Angola and Mozambique; Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi; the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Rwanda and Burundi; and Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya (see Figure 1.1). While most of these countries share some common features in terms of, for example, a colonial past and economic structures typical of less developed countries, this does not set them apart from other African countries or regions as considered, for example, in a forthcoming text in this DARG series: West African Worlds. Within this group there are, however, some clear subgroupings which have long-standing historical, political and geographical coherence which will be briefly considered before turning to some overarching themes of interaction which help to define this region.

South Africa has very specific status within this region as the most economically developed country. Its mineral wealth combined with its capacity for economic and political self-determination from 1910 (when independence from Great Britain was granted) gave South Africa the opportunity to develop as a minerals–energy economy with a significant degree of industrialisation (Fine and Rustomjee 1995) and, in regional terms, incomparable infrastructure. However as a white settler state which chose to pursue a political economic model based on racial inequality, the human development outcomes of apartheid South Africa’s policies for most of its people were manifestly disastrous. South Africa’s early escape from British colonial rule gave it particular local regional influence. Swaziland, Botswana and Lesotho (then Bechuanaland and Basutoland) spent much of their colonial period under threat of absorption into the nearby racist regime, which was a defining characteristic of their colonial experience and consequent neglect of their development (Spence 1965, 1968; Stevens 1967, 1972). They were also incorporated into a regional customs union dominated by South Africa: the Southern African Customs Union (SACU – see Gibb, Chapter 10 for further details). Namibia (the former South West Africa) suffered an even greater degree of dominance by South Africa which, during the First World War, occupied what was then a German colony in 1917 and was subsequently rewarded with a League of Nations mandate to administer the territory and essentially, if illegally, proceeded to incorporate it into South Africa as a fifth province. It did not attain independence until 1990, when it was Africa’s last major colony. Namibia is also a member of SACU, so these five countries form a particularly coherent subgrouping within which South Africa’s dominance is exceptional.

Figure 1.1 Eastern and southern African countries and membership of SADC, SACU and EAC

Note: The region as defined in the text includes mainland countries only

The next subgrouping indicated in the opening paragraph to this section is Angola and Mozambique. The essential binding link here is their experience of the specificities of Portuguese colonialism which both retarded their economic development throughout most of the colonial period and delayed their independence until 1975 after long wars of liberation against the colonists, both factors which facilitated their independent governments’ subsequent ‘choice’ of Marxism-Leninism as the framework for their political and economic policies (Abshire and Samuels 1969; Hammond 1966; Smith 1974; Bender 1978; Newitt 1995; Vail and White 1980; Munslow 1982). This was a defining moment for southern African regional interactions because it brought them both into devastating conflict with apartheid South Africa, which perceived the loss, to Marxist-Leninist governments, of two of its ‘buffer states’ against the tide of black majority rule as an unacceptable threat. Mozambique, particularly its southern region, had long been within South Africa’s economic ambit due to the logic of local transport geography, which made Lourenço Marques/Maputo the Transvaal’s natural port (Henshaw 1998), and its key role in South Africa’s migrant labour force. Angola was now also drawn firmly into the apartheid regime’s regional ambit played out through its so-called ‘total strategy’ through which it was endeavouring, by every means possible, to undermine the potential success of regional black majority rule and to prevent regional support for South African and Namibian liberation movements (Hanlon 1986, 1989; Johnson and Martin 1989; Davies and O’Meara 1985; Potts 1992). In Angola and Mozambique this included South African backing for anti-government forces which led to devastating destabilisation and the reversal of any positive developmental trends. Both countries also became key players in the anti-apartheid regional grouping of the Front Line States (FLS) which included Botswana, Zambia and Tanzania and was another important political linkage within the region.

Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi form another coherent subgrouping on a number of grounds. They were all British colonies; they are all landlocked; they all formed part of an earlier, institutionalised regional grouping, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (1953–63) which was dominated by Southern Rhodesia (i.e. colonial Zimbabwe). Both Zambia and Malawi gained their independence in 1964. Zimbabwe, on the other hand, had to wait until 1980 and its African people, as in Angola and Mozambique, had to wage a long and bloody liberation war against white settlers. It then joined the FLS, providing yet another regional linkage.

The southern African regional grouping, the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC), was also formed in 1980, its essential binding economic and political aim being to reduce dependence on apartheid South Africa. The original membership included all 10 countries so far considered (except, of course, South Africa) plus Tanzania (largely because of it FLS status). The Namibian liberation movement, SWAPO, had observer status. The political linkages and status forged through this grouping, and the liberation struggles against white minority rule more generally, have proved long-lasting (Sidaway 1998) and remain essential factors in explaining contemporary regional politics. South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994 paved the way for its shift from SADCC’s ultimate enemy to becoming the potential hegemon of a new southern African group, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) (Ahwireng-Obeng and McGowan 1998; Simon and Johnston 1999; Simon 2001).

SADC now includes the DRC, thus pushing much further north the logical boundaries of regional study. The inclusion of this huge country, by far the largest in the region (see Table 1.1), into the ambit of any coherent study of southern Africa, if SADC membership be deemed to be a defining characteristic, has however tipped the balance of regional coverage in a significant way. To be brief, as the issues are covered in detail in Chapter 9, development issues in the DRC cannot be coherently considered without coverage of Rwanda and Uganda, both of which have been key players in its ‘liberation’ from Mobutu and then its civil war, which also brought in Angola, Namibia and Zimbabwe (providing further political linkages within the region defined in this book, although also leading to tensions within SADC) (Financial Times 2001; Regional Roundup 2002). Since South Africa, Zambia and Botswana have all played important diplomatic roles in trying to end this conflict – a regional example of the concept of ‘African solutions for African problems’ – the political geography rationale for the region as covered in this book is enhanced. As the DRC’s economic resources were a key reason for its SADC membership, with South Africa a key player in that decision, and Zimbabwe, Namibia and Angola are now also economically involved in the DRC, the economic geography rationale is also growing.

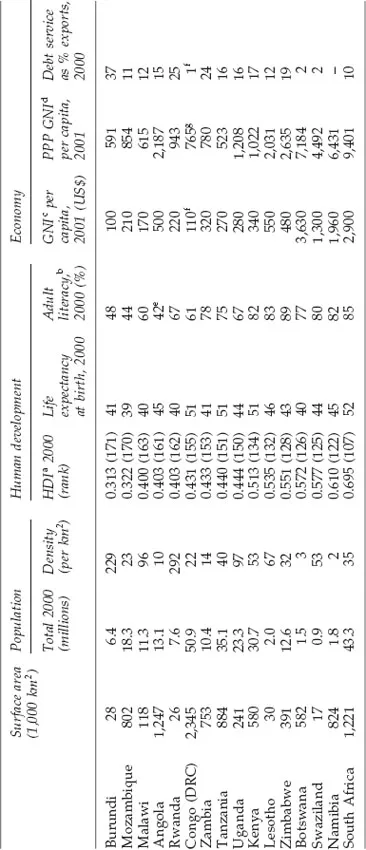

Table 1.1 Eastern and southern Africa: socio-economic indices 2000/1 (ranked by HDI value)

a. Human Development Index and world rank in 2000 in brackets.

b. Literacy rates are for the 15+ population.

c. Gross national income, the term now used in World Bank tables, is the same as gross national product.

d. Purchasing power parity dollars.

e. UNICEF estimate for 2001.

f. World Bank (2000) estimate for 1998.

g. 1998 estimate.

Sources: GNI and PPP per head from World Bank (2002); other figures from UNDP (2002) unless otherwise noted.

The inclusion of Kenya and Burundi becomes inevitable once the region includes Rwanda, Uganda and Tanzania. Rwanda and Burundi share a host of environmental, historical, political and economic features and are in any case encapsulated by the region as defined. Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania form their own economic grouping, the East African Community, and are frequently considered as a regional unit. Otherwise Kenya is the one country in the region covered in this volume for which there is arguably no strong political or economic rationale for studying it alongside southern Africa. However, like so many of the countries to the south, Kenya was a white settler colony, which very firmly links it to the south in terms of its developmental heritage from colonialism (Mosley 1983; Kennedy 1987).

There are also some important environmental features which help to define the region covered in this volume, although there are exceptions in every case. As Figure 7.1 indicates, the boundary between ‘high’ and ‘low’ Africa provides, to some extent, a natural boundary to the west of the region, although it divides the DRC in two. Also, as illustrated by Chapter 8, significant proportions of many of the countries in the region are designated as drylands. Yet again, though, the DRC is exceptional here, as are Rwanda and Burundi. Inevitably, any region contains discontinuities, and arguments can be made for or against the inclusion of its geographically outlying members and are, to some degree, subjective. For example, the coverage of eastern and southern Africa here is confined to the mainland, and excludes Madagascar, Mauritius and the Seychelles. The latter two are, nevertheless, SADC members, but it has been deemed that the specificities of their small island economies and their lack of involvement in intra-regional political affairs make them too exceptional to be included logically in a study of development trends and challenges (although it makes sense to mention them in Chapter 10 on trade as they are affected in similar ways to other countries in the region by recent trade regulation changes). Similarly it is arguable that if Kenya is covered, then why not Somalia, Djibouti and Ethiopia? However, this would stretch the intraregional links south to the tip of the continent beyond any meaningful rationale.1

Overall, the essential justification for the coverage of the 16 countries included here as ‘eastern and southern Africa’ is based on their level of interactions. It is worth noting, in terms of the developmental prospects and problems of the region, that these have been characterised as much, if not more, by conflict than co-operation. Furthermore, the countries of the region are highly diverse in terms of their natural resource base, and levels of economic and human development (see Table 1.1). It includes Burundi, Mozambique, Malawi, Rwanda and the DRC which, in terms of both crude per capita income levels and the UNDP’s Human Development index (which is a better measure of ‘development’ as it combines income, education and life expectancy data), are among the least developed countries in the world. Angola, as can be seen, has much higher per capita income levels mainly because of its vast oil revenues, but these have been of little relevance to most of its population whose welfare and livelihoods have been ravaged by decades of war. Nearly all the countries of the region are classified by the World Bank as ‘less developed’ or low-income countries, which is another binding characteristic of central significance to the themes of this volume. Botswana (which has the highest nominal per capita income, having now surpassed South Africa in this respect), Swaziland, Namibia and South Africa are, however, ‘middle-income’ countries and, as discussed by Gibb in Chapter 10, South Africa is deemed to have ‘transitional’ development status in trade negotiations. Tony O’Connor deconstructs regional statistics related to poverty (and their reliability) in great detail in Chapter 4, to which the reader is directed for further analysis. It is worth noting here the following points. First, although great inequalities in income and welfare between people is an important characteristic of all the countries of eastern and southern Africa, South Africa’s and Namibia’s indices need particular care in interpretation as race is still such an important correlate with privilege in these two countries (as, indeed, it still is in Zimbabwe, although there the recent economi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Boxes

- List of Contributors

- Series Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Publisher’s Acknowledgements

- 1 Development challenges and debates in eastern and southern Africa

- 2 Demographic change in eastern and southern Africa

- 3 Structural adjustment in eastern and southern Africa: the tragedy of development

- 4 The persistence of poverty

- 5 Natural resources: use, access, tenure and management

- 6 Agricultural production in eastern and southern Africa: issues and challenges

- 7 Water resources and development challenges in eastern and southern Africa

- 8 Desertification in eastern and southern Africa

- 9 Geographies of governance and regional politics

- 10 International and regional trade in eastern and southern Africa

- 11 Regional urbanisation and urban livelihoods in the context of globalisation

- 12 Conclusion

- Index