![]()

![]()

A forest is not simply a stand of trees. It is a living and breathing ecological community. Towering maples, oaks, and spruces dominate this landscape, but they are a minority when it comes to the total number of plant and animal species present.

An average forest may host anywhere from 10,000 total species in a temperate climate to several hundred thousand species in a tropical one. These species have adapted to thrive in unique microclimates within the forest, ranging from open woodlands to dense treetops.

The forest floor, in particular, thrives with life. It supports a plethora of species that bound, crawl, dig, fly, hop, roll, slither, and walk. One square acre (0.16 square hectare) of South American rain forest has been estimated to support more than 165,000 insect species.

Forests Defined

A forest is an ecosystem anchored by long-living woody vegetation. The number and density of species in a forest depend on the climate, topography, soil conditions, and availability of freshwater. Forests are found in both warm and cold locations, and they range in size from less than 1 acre (0.4 hectare) to 50 million acres (20 million hectares). Tree species live for very long periods. The oldest known individual specimen was a pine tree in eastern Nevada, estimated to be 4,862 years old when it was cut down in 1964 for research purposes. Trees also grow in groups, called clonal masses, due to their ability to generate genetic copies over time. The oldest known clonal root system is in Dalarna, Sweden, and it is approximately 9,950 years old.

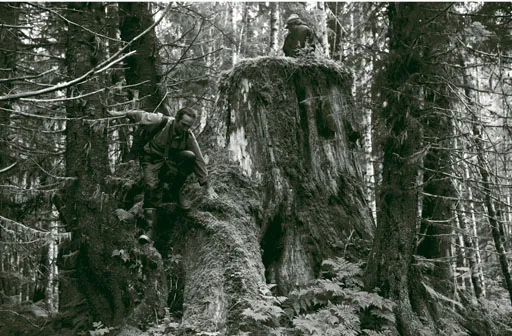

Scientists study trees in the Tongass National Forest in southeast Alaska. As a result of logging since the 1950s, only 30 percent of the old-growth forest remains. Covering 26,250 square miles (67,988 square kilometers), the Tongass is the largest publicly owned forest in the United States. (Melissa Farlow/National Geographic/Getty Images)

A forest provides a set of measurable benefits that are known as ecological services. One of the greatest assets of a forest is the fact that it is able to take in large amounts of carbon dioxide and convert it to oxygen and energy in a process known as photosynthesis. A forest also cycles plant nutrients from the soil into living material and back again. Roots absorb nitrogen and eventually deliver it to leaves, promoting new growth. Once the leaves fall to the ground and decompose, the nitrogen is again processed into the soil.

A forest holds water and protects watersheds, thereby providing a stable environment for a diversity of species. Forests even limit weather events such as droughts. This is performed by individual trees that hold water over time, as well as by the network of closely growing species of trees and other plant species.

Forest ecosystems are always changing in a process known as succession. A tree species is not static; it will emerge, grow, and eventually die to be replaced by another tree. Succession can occur over a number of years or be triggered by a disturbance such as a flood or a fire. This level of change allows a forest to thrive and evolve.

Twenty thousand years ago, forests covered half of all land on Earth. This habitat has been severely reduced due to human-generated deforestation and development, especially over the last 250 years. Today, scientists estimate that forests make up approximately 28 percent of all land, covering 9 percent of the planet.

A total of 13.8 million square miles (35.7 million square kilometers) of forest is broken down into six different types of ecosystems, including boreal, temperate deciduous, temperate evergreen, tropical rain, tropical seasonal, and savanna. Forests and their associated wetlands host a documented 1.75 million species, an estimated 2 percent of all living creatures.

Up to 55 percent of all forests is located in temperate zones, with Russia and North America supporting up to two-thirds of the nearly 7.6 million square miles (19.7 million square kilometers) of temperate forests. The remaining 45 percent is found in tropical areas, with Africa, Central America, and South America holding nearly two-thirds of these 6.2 million square miles (16.1 million square kilometers) of forest.

Origins of the Forest

Although the Earth is approximately 4.6 billion years old, precursor forest species did not appear until 420 million years ago during the Silurian Period. Scientists believe that the first forests dominated by trees had not evolved until 225 million years ago.

The first life on the planet emerged roughly 3 billion years ago in the form of marine algae and unicellular floating organisms. The first plants on land included the family of Rhyniophytes, which were composed of simple, upward-growing shoots, ending in spore capsules. These vascular species relied on thin root hairs rather than thick roots to absorb nutrients; this might have been a sign of their evolution from an aquatic environment, where hair-like roots are common. The plants relied on distribution of their spores to reproduce and only thrived in a warm, moist environment. Most species of plants did not exceed 3 feet (1 meter) in height during this time.

| PERCENTAGE OF FORESTED LAND, BY REGION | |

| Region | Percentage Forested | |

| Africa | 24 | |

| Asia | 19 | |

| Central America | 26 | |

| Europe | 29 | |

| North America | 38 | |

| Pacific Islands | 11 | |

| Russia | 34 | |

| South America | 47 | |

| Source: United Nations Forum on Forests, 2007. | |

More than 345 million years ago, a second major evolution in plant forms began. Several families of plants developed larger leaf systems, thicker stems, and substantial roots. These included ferns (from the classes Psilotopsida, Equisetopsida, and Polypodiopsida) and horsetails (from the class Equisetaceae). Many of these species experienced accelerated growth; for example, the tree-sized club moss grew up to 70 feet (21 meters) tall.

Evolving vascular plants included gymnosperms, a new species of woody plants that relied upon seeds to reproduce. Gymnosperm seeds were better protected for reproductive success than spores, had built-in nutrients to support the plant embryo, and could endure a greater range of temperatures. While some of the earliest vascular plants became extinct in the process of these changes, a few species of gymnosperm called conifers evolved into pine trees that reached 200 feet (61 meters) tall.

Around the time that dinosaurs vanished from the planet, about 120 million years ago, a third major evolution in plants was under way. New plant species called angiosperms appeared. They relied on flowering as part of a new and more effective means of reproduction.

While the gymnosperms simply released their seeds to the air—for instance, in a pinecone—angiosperms produced a flower that was fertilized by an insect or bird. In the process of feeding on the flower’s nectar, the visitor carried pollen from one flower to another. Inside the pollen grains were male sperm, and when these sperm were delivered to the female part of the flower, this resulted in the production of fertile seeds that were protected inside a fruit or as part of a nut produced by the plant or tree.

When this fruit was ingested by an animal or a bird, the seeds were carried away. Once released back into the forest as waste, the seed grew to become a baby tree. Nuts also could be carried away and buried by animals for safekeeping; those not dug back up often would grow to become trees. Thus, the angiosperms became the dominant tree species, and they remain so in today’s modern forest.

Gymnosperms include the gingko tree (Ginkgo biloba) and up to 115 species of pine tree (Genus Pinus). Angiosperms make up the largest diversity of land plants estimated at over 250,000 species, including up to 125 species of the maple tree (family Aceraceae).

Forest Types

There are different methods to classify a forest—by species, age, ownership, climate, geography, economic or cultural use, or any combination of the above. In the most basic approach, forests can be broken down into two major tree categories: coniferous and deciduous.

The name conifer is a Latin word meaning “cone-bearing,” and it refers to the conical shell that holds the seeds of these evergreen trees. The name deciduous comes from the Latin word decidere, meaning “to fall off,” and refers to the seasonal loss of leaves that these trees experience at the beginning of winter. While one of these two types of trees may make up or dominate a forest, mixed coniferous and deciduous forests are common worldwide.

Coniferous Trees

Conifers are the oldest and largest trees on Earth...