The study of global climate change is an exciting and gloomy enterprise. The excitement comes from discoveries being made in the uncharted realm of a changing global climate. The gloom comes from the nature of many of those discoveries. Mainly, we are seeing that there’s trouble on the horizon. How serious is the trouble depends on how far out we look, and on our capacity to avoid or adapt to the changes heading our way. Actually, it’s less the changes heading our way than it is the changes we are driving ourselves into.

Climate Change Basics

In order to understand why researchers are increasingly troubled about the extent and direction of global climate change, we’ll need to review some climate change basics. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) distinguishes weather (condition of the atmosphere in a particular place over a short period of time) from climate (average weather over 30 years or more). Both weather and climate are variable. The difference between climate variability and climate change is the persistence of “anomalous” conditions: “events that used to be rare occur more frequently (summertime maximum air temperatures increasingly break records each year), or vice-versa (duration and thickness of seasonal lake ice are decreasing with time).”1 Both weather and climate can be quite variable, but not constitute climate change. Climate change is when weather and climate average values shift and variability increases over at least a 30-year period, breaking records, exceeding upper and lower values, or varying in new ways from past observations: earlier or later higher highs, or lower lows, more frequent or less frequent weather events.

There has been much climate variability, but not much climate change since the end of the last Ice Age, around 10,000 years ago. Patterns of droughts, heat waves, cold spells, monsoons and hurricanes, and blizzards established a range of expected climatic variability in different regions of the world. It was during this climatically stable “interglacial” period that humans moved from exclusively hunting and gathering and began cultivating crops. Throughout these past 10 millennia, carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmosphere remained fairly constant, between 260–280 parts per million (ppm).

CO2 is one of several greenhouse gases (GHGs) frequently cited in discussions of climate change. The other two major GHGs tracked by scientists interested in understanding climate change are methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O). CO2 is the most widely used indicator of levels of GHGS in the global atmosphere partly because its effects last the longest and it makes the largest contribution to global temperatures. Stable levels of atmospheric CO2 over the past 10,000 years started to change when the Industrial Revolution increased the use of fossil fuels in agriculture and industrial production. Work that had been done by hand or with animals until that time began to be done by machines driven by coal, oil, and gas. Burning these fossil fuels released their stored carbon in the form of CO2 into the atmosphere, increasing levels of CO2.

The use of machines in place of human labor not only transformed factories, it revolutionized agriculture. Fossil fuel-driven farm machinery changed small-scale farming into large-scale agriculture, factories replaced craft enterprises, roads were built, growing populations moved from farms to cities, and the United States and other industrial countries became mainly urban societies dependent on food from machine-driven agricultural production. Mechanized agriculture broke new land, releasing carbon from the soil where it had been buried for hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions of years. Extraction and combustion of fossil fuels for heat, cooking, farming, industry, and transportation released into the atmosphere billions of tons of carbon from coal, natural gas, and oil that had been sequestered underground for hundreds of millions of years.2

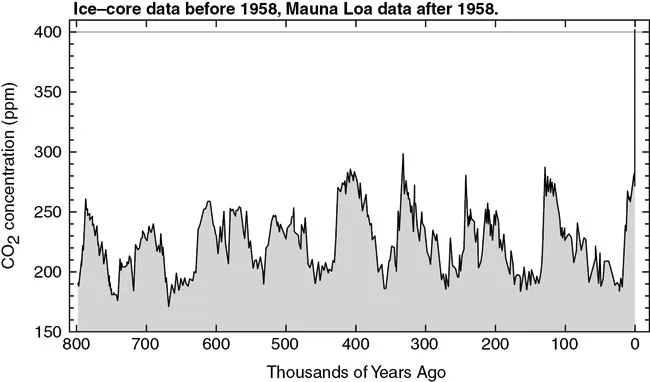

Figure 1.1 Global Carbon Dioxide Concentrations (PPM) Over the Past 800,000 Years7

The growth of CO2 levels has accelerated dramatically in the last two centuries. Atmospheric CO2 was about 280 ppm in 1850 at the start of the Industrial Revolution, and had increased only 20 ppm (7 percent) during the previous 800,000 years. In 2015, atmospheric CO2 exceeded 400 ppm, an increase of 120 ppm (33 percent) in only the past 155 years.3 Scientists determine CO2 concentration using a variety of methods. Instruments such as infrared or chemical sensors directly measure atmospheric CO2, and past atmospheres can be analyzed using air bubbles in ice cores drilled in polar ice sheets. More inferential proxy methods use marine sediments, fossil plants, or rock weathering.4 Figure 1.1 shows data from both instruments and ice cores to chart atmospheric CO2 levels during the past 800,000 years.5 Before 1958 ice core data are from Greenland and Antarctica; beginning in 1958 instrument data are from Mauna Loa, Hawaii.6

The graph in Figure 1.1 shows the cyclical rise and decline of CO2 levels associated with glacial minima and maxima over 800,000 years. The repeating peaks and valleys of CO2 in the graph are initiated mainly by solar cycles and Earth’s orbital changes and amplified by positive feedback processes.8 The noticeably regular patterns in CO2 variations over these 800 millennia are a reminder that there are many natural forces shaping Earth’s planetary systems, including solar cycles and solar activity, volcanic eruptions, changes in the Earth’s orbit, and major shifts in the Earth’s tectonic plates. An important point to make is that human civilization does not exist throughout the vast expanse of this period, but appears on the scene far toward the right of the graph, fewer than 10,000 years ago.

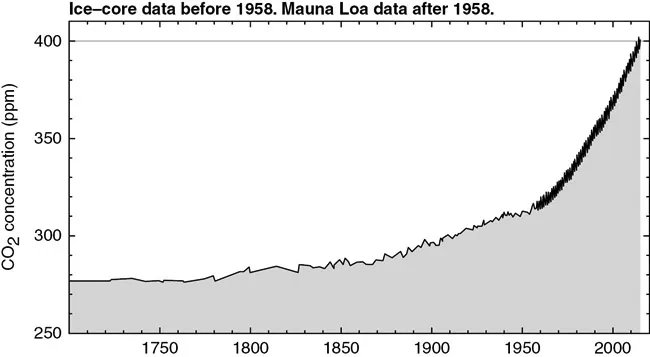

Figure 1.2 Global Carbon Dioxide Concentrations (PPM), 1700–201410

In Figure 1.1, it’s easy to overlook the vertical line on the right side of the chart just above year 0, a line that rises straight up from 280 to 400 ppm. That vertical line shows the increase in CO2 in the last 165 years. It is easier to see this increase in Figure 1.2, which charts levels of CO2 from 1700 to 2012. Figure 1.2 shows that CO2 levels are fairly stable until around 1850, when the upward trajectory begins, and accelerates during the second half of the 20th century. The thick lines in the graph are seasonal variations obtained from daily CO2 measurements that Charles David Keeling began in May, 1958.9

With very few exceptions, scientists examining these data identify human activity as the major cause of the precipitous rise in CO2. In particular, researchers point to our use of fossil fuels and their GHG emissions as the current most powerful driver of global climate change. The link among increased use of fossil fuels, rapidly rising CO2 levels, and major changes in the global climate system constitute “anthropogenic” (human-caused) climate change.

Carbon Dioxide and Climate Change?

What exactly do atmospheric CO2 levels have to do with climate change? CO2 is critical to life on Earth. Plants use CO2 in photosynthesis to grow and produce oxygen, and in turn, plants are a food source for other forms of life, including humans. CO2 helps provide Earth with an atmospheric envelope, retaining the sun’s heat and keeping the planet warm. The fairly constant levels of CO2 present in Earth’s atmosphere during the development of human civilization have increased dramatically. These elevated levels of CO2 and other GHGS are raising global temperatures and warming the world’s oceans. CO2 has another effect on the oceans, which absorb about 30 percent of the CO2 we release into the atmosphere every year. CO2 absorption changes the chemistry of seawater, causing ocean acidification, which contributes to the decline of shellfish populations, the bleaching of corals, and threats to the species that depend on them.11 The various changes associated with increased levels of CO2 are producing a cascade of related, and often unpredictable, outcomes, the study of which has become climate change science.

Scientific concerns about the nature and extent of climate change underway around the planet led to the creation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988. The IPCC was established by the WMO and the United Nations (UN) to provide the world with the most current and accurate available scientific information about climate change’s potential environmental and socio-economic impacts to assist in formulating realistic response strategies.12 The IPCC does not conduct research; it gathers data from scientists in UN member states. Every seven years, these scientists compile “Assessment Reports,” which are reviewed and must be unanimously approved by political representatives from all countries and the reports’ lead authors. In its 2013 Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), the IPCC reported:

The atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxid...