![]()

Part I

Theatre in open spaces

A new beginning

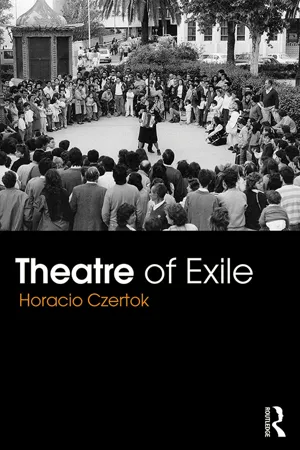

Grassroots theatre festival, 1977, Casciana Terme, Italy.

It’s been raining for two days and the marquee floor is all mud. We’re about to do our play Herodes for an audience made up mainly of young actors from what they call ‘grassroots theatre groups’. We’re exhausted. In Argentina, death squads from all three branches of the armed forces, police and secret services are still torturing people in their thousands and ‘disappearing’ them, with the silent complicity of the international media. For months now, Teatro Nucleo has been travelling the length and breadth of Italy, hosted everywhere by grassroots organisations. With Herodes, we’ve been trying to make people aware of what’s happening in Argentina and, at the same time, survive as a theatre group. But it’s no use. Nobody – from the mass media to the big political and cultural organisations – wants to listen. It’s dangerous as well, especially for our families still down there, but also for us personally. The Argentinian embassy knows where we are. There are secret agents on the prowl, aided by the Italian secret services. They give us a hard time whenever we go to the consulate for documents.

Herodes is no exercise in rhetoric. It is a performance about something that happened to me, something that directly involved me and the people I worked with. In Buenos Aires, I was in charge of external relations for my theatre group, Comuna Baires. On the morning of the 14th of February 1974 I was seized by four people. They bundled me into a green Ford Falcon, beat me and hooded me. I woke up naked, tied to something that looked like a metal bed frame. I was all wet. They had thrown a bucket of water over me. There was a radio turned up loud and somebody started using a picana on me – a torture instrument with an electrode that they apply to different parts of your body. The other electrode is connected to the electricity mains and your body acts as a bridge. They had a dossier on our group’s activities in Italy and Argentina, and they kept on reading out excerpts from it and touching me with the picana on my most sensitive parts. There was nothing they wanted to know that they didn’t know already, and that was one of the most terrible things about it. They just wanted to terrorise me. One morning they untied me and took me outside, stood me against a wall and removed my hood so that I could see my torturers there before my eyes with their guns. I was trembling and dirty. I realised that I was done for. If they let you see them it means you won’t ever be a witness. They told me ‘it’s all over for you; that’ll teach you to be a subversive’, and they fired at me. I still see the flashes and smell the cordite and feel the bullets thudding into the wall next to me. It was a mock execution. I also still hear them laughing and joking about what they did and, strangely, it makes me think of Dostoyevsky; that’s what he must have felt like when they did it to him. Then they took me to have a shower and get dressed and took me to Retiro railway station and set me free. They told me to warn my group about what awaited them and to get away, otherwise next time it would be for real. That was why Comuna Baires, with the help of some European organisations, left for Italy immediately afterwards. I decided to stay on and founded Teatro Nucleo, which kept going for as long as possible – another two years – in Buenos Aires. After what I had gone through, I was determined not to just drop everything and run.

So, here we are, on this wobbly stage in the mud, in a tent that barely keeps the rain out. Three of us, the only ones remaining – Cora, Hugo Lazarte and myself – because the others have either gone back to Buenos Aires or given up theatre. They didn’t see any point in carrying on in a different context and place. We three – four with our son Maximiliano, aged four. We three and all those young Italians. They don’t know a thing about Argentina, about the desaparecidos, the dictatorship, the torture; and yet so many young people – Italians just like them, perhaps two thousand sons and daughters of emigrants – have disappeared in Argentina. They don’t realise. There is nothing deafer than someone who doesn’t want to hear. Them and us. Herodes is a simple performance, a visual, physical and direct metaphor of what we are living through. There is a torture scene. We get to it. Hugo and I are the torturers, working on the tormented body of Cora. At this point some of the audience can’t stand it any longer and the mutterings and protests turn to action. They invade the stage and interrupt the performance. One of them grabs me and I push him roughly out of my ‘prison’. Eugenio Barba wrote to us later:

standing on a wobbly chair in the mud in that tent, I saw you in your performance in Casciana and it was like a knife in my stomach, like the other side of the moon, something we in Europe can only guess at; our senses can’t come to terms with it concretely. And I saw those girls crying – the ones who did the feminist sketch the evening before – like children who’ve run away from home and then start crying when the night comes. Was it from fear? or loneliness? or because of the shadows falling over them menacingly? Then there were all those rivers of words that started flowing and as I stood there watching you I thought about you going go back to your everyday lives as exiles the next day, with your memories, emotions and hopes on the other side of the ocean. What a sad continent ours is – sad because you won’t ever be able to leave it [ … ] don’t give up, don’t stop caring, don’t let the things people say rob you of your strength. We all embrace you … 1

We became an event at the festival. The RAI (Italian state television) film crew that had already put their cameras away filmed everything, including a desolate Cora, before a shocked audience, saying ‘how can I explain, how can I explain to you what is happening at this very moment in Argentina? What you’ve heard here today is just a small part of it.’

And this was how we realised that our attempts to get people involved, here in Europe, in the way we had hoped, were ineffective. To make people aware of what’s happening in Argentina you have to use different media. With theatre you can and must do other things.

Ferrara: meeting Antonio Slavich

A few months earlier, while working on an animation project in Sassari mental hospital, we had met Antonio Slavich, who suggested we set up a theatre workshop in Ferrara psychiatric hospital, of which he was director. Italian Law 180 – which saw mental hospitals as places of marginalisation and repression that were unsuitable for the treatment of psychic suffering and subsequently abolished them – was being drafted at the time and was to become law the following year. He asked us to submit a project. He knew about our work based on actors’ self-awareness and social interaction and, in his own words, noted that

in the expressive force of their gestures and their shouted discussions there was something different to the quips and asides you would normally expect of travelling court jesters [ … ]. So we dined together and fraternised. They said their poetic, anger ridden things about about the violence that surrounds us and about their desire to break down theatre as an institution, I talked about my utopian dream of breaking into mental hospitals with expressive means other than the indispensable pickaxe; and so, it was simply a matter of where and how we would work together [ … ] a way could be found.2

Fresh in his memory was the Gorizia adventure where he had worked alongside Franco Basaglia. His arrival in Ferrara coincided with the transformation of the mental hospital there into an open institution and he knew that a certain kind of theatre could be useful in this. He needed forces to deploy to help him break the encrusted mould of psychiatrists, nurses, patients and citizens, and actions that would contribute to the generation of a new consciousness. Slavich was interested in the relationships we had formed with psychiatrists and psychologists in Argentina and the results we had achieved. Above all, he was interested in what could be achieved by combining Argentinian and Italian mental hospital experiences.

Ferrara psychiatric hospital was like a relic of anxiety and terror in a forgotten corner of the town, left over from the Middle Ages. A thousand people locked in a paradoxical existence, governed by rules unfit for human beings, branded as ‘mentally ill’, forgotten about and subject to treatment designed not to cure but to contain, to make them die alive. Astonishing acts of violence that had become an everyday routine and were therefore acceptable, with drugs taking the place of straitjackets. This was the reality that Slavich wanted to transform at all costs, to bring it into line with contemporary civilisation. The idea of opening up mental hospitals, developed at Gorizia lunatic asylum in the 1970s by Basaglia and Slavich himself, had been proven to work. Mental hospitals were being opened up to let the people in them out, and to let everybody else in so that they could see what they were like.

The project was a complex one. As well as theatrical experience workshops for both patients and staff, led by Cora Herrendorf, there was also the introduction – with the help of theatre techniques – of a new kind of internal circulation in the hospital, with the abolition of the old barriers that separated the wards. The structural barriers had already been removed, but the mental ones remained firmly in place. The patients didn’t circulate. For months, we worked with the patients in the still-closed wards, a mixed group of patients, psychiatrists and nurses in the hospital outdoor spaces and a group of students in a hall in the town. As soon as one of the wards was vacated, the young people in the group became actors and builders and installed a theatre there, starting immediately to schedule performances and other activities. The image of the mental hospital was turned on its head, transformed from a place to hide or avoid into a place of caring and learning how to coexist. The theatre in the former lunatic asylum became something previously inconceivable in Ferrara: a theatre cooperative that generated social aggregation, teaching activity and sociocultural action, as well as performances that toured the world. For the first time ever, Ferrara was exporting theatre.

So, working together with us and alongside actors, the patients were able to discover new possibilities. This was how Luci (‘Lights’), our first street theatre performance, came into being, with the images of the first plays we had seen in Europe – by Odin Teatret, the Teatro Tascabile of Bergamo, the Comediants and the Théâtre du Soleil – fresh in our minds; plays that suggested new directions in theatre to us.

In 1978 we attempted a dangerous and unfruitful return to Argentina. Ten months of activity: theatre seminars in Buenos Aires and Tucuman, articles in newspapers, screenings of the film made in Ferrara of our work in the mental hospital, the eighth issue of our Cultura magazine (funded by the Odin Teatret), about the Theatre Groups Meeting we attended in Ayacucho in Peru. In October, military personnel in Buenos Aires City Hall brusquely cut short our Odin in Argentina project and forced us to pack our bags again.

That was how our group decided to settle in Ferrara, where, in a former psychiatric ward made available to us by the hospital management, we set up Teatro Nucleo’s new headquarters, working together with the newly recruited actors from Ferrara. This theatre, in what used to be Ward B of the hospital in a street called Via Quartieri, was the first of many we created, but was especially important because, as Slavich said, it stopped things from going back to how they had been before. It gave those spaces back to the town, transforming them into a place of culture. We had to leave ten years later when the city council and university decided to put the Faculty of Architecture there. We then moved to the outskirts, to Pontelagoscuro, where the new theatre was to be installed in a disused cinema.

Pedagogy and theatre practice: the group

We created a pedagogy capable of overcoming the barriers that face young people looking for a purpose in life, and we realised that these were the same as those faced by prisoners who want to be – and remain – free after their release, and by the mentally ill who want to be treated like anybody else. The common denominator in all this is that, at first, none of these people wanted to be actors or to do theatre. They saw theatre as something culturally miles away from them and were totally indifferent to it. Theatre didn’t care about them nor they about it. It was something for the ‘cultured’ classes, the ‘dominant’ classes.

We were exiles but didn’t want to accept the condition of exile – boundless compassion but a passport valid only as far as the borders of the country hosting us. We didn’t want charity of any sort. We wanted to be what most gave us our dignity back: emigrants. We wanted to pay for our own rent, living expenses and children’s education, like anybody else. And we wanted to do it with the theatre we’d learnt in Argentina and that had got us exiled – an ethical theatre based on the premise of a self-searching, individual revolution and the creation of a ...