eBook - ePub

Technical Management for the Performing Arts

Utilizing Time, Talent, and Money

This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Technical Management for the Performing Arts

Utilizing Time, Talent, and Money

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Technical Management for the Performing Arts: Utilizing Time, Talent, and Money is a comprehensive guide to the tools and strategies of a successful technical manager. This book demonstrates how you can coordinate personnel, raw materials, and venues, all while keeping a production on a tight schedule and within budget. From concept to realization, through nightly performances, Technical Management for the Performing Arts focuses on the technical and organization skills a technical manager must demonstrate, and emphasizes the need for creativity and interpersonal management of a team.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Technical Management for the Performing Arts by Mark Shanda, Dennis Dorn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction

Chapter 1

Meet the Manager & the Triangle

What and who are technical managers? What is a Time, Talent, & Money Triangle? How are these terms relevant to those of us engaged in aspects of live and recorded entertainment? And, if so, what’s the relationship?

Introducing the Technical Manager

The principal purpose of the entertainment industry is to tell a story. The story may be fiction or nonfiction, live or recorded, sequential or pieced together, true or fantasy, simple or complex. Perhaps the story is complex yet simply conveyed. No matter how the project is categorized, any entertainment enterprise is an effort that can become very complicated as the number of participants expands.

In what is perhaps an extreme example, consider the setup, performance, and teardown of the NFL’s annual Super Bowl Halftime Show (SBHS). While it is doubtful that the event was ever conceived to be small in scope, the entire concept of this halftime show might have started initially with the unpretentious idea of featuring an outstanding singing group to appear midfield and fill the space with aural delight while the football teams disappear into their respective locker rooms for a pep talk. To do justice to the performers, however, the huge cubic volume of the venue demanded technical support, i.e., microphones, speaker clusters, audio equipment board operators, and sufficient stage lighting luminaires and controllers to allow the large audience to focus its attention on the midfield activities. Technical support requires gear and crew, who in turn require the oversight and coordination of technical managers. Today, the SBHS has grown to include elaborate staging, extraordinary props, performers’ flying gear … and the need for even more technical managers.

As a far less elaborate example, take the situation of a “stand-up” comedian who is doing a nightly one-man routine. The stage consists of two 4 × 8 platforms located in a corner of the room. Even in this small venue, the performer will likely request a mic, even if the audience will have no difficulty hearing without one, and at least two spotlights to ensure focus on the performer. Additionally, the mic will bolster the performer’s confidence and give him or her a prop to occupy twitchy hands.

In many instances, within a short time, the production values associated even with this small setting will grow so that enhanced lighting and audio systems will be installed that require additionally sophisticated technicians and at least one technical manager. Grow the venue a bit more and the production values will become more complex, as will the coordination. Performance events require multiple disciplines and the involvement of many individuals to support the performance and enhance the audience experience. Guilty by association, all these technicians and their supervisors, as well as all performers, are part of the event and subsequently collaborators in its execution.

The Team Behind the Scenes

While the “talent,” a.k.a. performers, are always the focus of any filmed or live-performance event, the success or failure of these events is commonly due in no small part to the genius and collaborative abilities of the teams of artisans, craftspersons, and managers who support the talent and story in ways that enhance the delivery of the performers’ actions and the script. This supporting technical crew involves multiple teams of talented individuals and technical managers, all of whom contribute to the success of the overall venture.

The normal support team includes directors and choreographers; designers; dramaturges (sometimes); and key technical personnel in the fields of scenery, costumes, lighting, effects, props, and multiple similar disciplines. Together, along with supporting artists and craftspersons, these team leaders join their imaginations and creative skills to develop and enhance the story formation. Depending on the type and scale of the project, a team may be only a handful of people or, in the case of opera, industrials, arena concerts, and film, hundreds and even thousands.

Regardless of the importance of the lead creative team, the focus of this book is not about them. Our focus is on the contributions of the important midmanagement leaders who work alongside and coordinate the work done, most of them unseen by any audience.

The title of each manager in these collaborations varies from organization to organization, although chief lighting technician, costume supervisor, show rigger, prop supervisor, and SFX coordinator are some common titles. This person, in whole or in part, is vested with much or all of the overall management of backstage personnel, schedules, physical facilities, and equipment, as well as the coordination of various production elements. This is the person to whom this book is dedicated and to whom it will be most useful.

Where Technical Managers Originated

Although history tells us of large-scale productions performed millennia ago, the management of such events has changed significantly since the mid-20th century. While this may only be simple conjecture, most likely technical managers derived from lead artisans, who oversaw the work of other craftspersons. Years ago, everyone learned their skills through apprenticeship and long periods of on-the-job experience. The Middle Ages in Europe saw the development of guilds whose craftsmen members were residents of their performance venue communities and familiar with their surroundings, their materials, and with each other. The pattern stayed much the same until the 20th century.

Beginning in the mid-1960s, rock-n-roll arena tours became more commonplace. They brought with them changes that have permeated the workings of even small local performance venues today. Production values became vastly more complex and certainly more corporate than in centuries past. With increased sophistication came a growth of disciplines, new and expanded technologies, and a recognition of the need for greater collaboration and efficiencies.

In professional circles, the lead craftsman’s scope of responsibility widened to include tasks of an increasingly managerial nature. Over time there has become more knowledge to acquire, more skills to master, and more facets to coordinate. The result is that most craftspersons cannot function as independently as they had in the past. And the pace at which work needs to unfold requires that things be created at multiple locations, adding complications to the coordination and assembly of the numerous elements that have to come together and gel within tight schedules.

This change occurred first in professional circles, but quickly this pattern became part of academic and community organizations as well. For the latter, resistance to change and more limited resources meant a slower-paced recognition of the new trends. Today’s fast-paced event timelines and the desire to train students to function ASAP after leaving formal training has resulted in more educational organizations incorporating more business-style management techniques to meet organizational expectations.

While a handful of performing arts professional programs within academic institutions have adopted more management-oriented training programs for students, there are currently few, and rather limited, published resources available. While most recently penned texts include a chapter on organizational structures, few provide any instruction in necessary management skills to function as a technical manager. In the past, these academic/professional programs have focused on the “nuts and bolts” of production work, and for the most part they still do. The emphasis remains on mastering technical/artistic skills rather than on development and awareness of people (soft) skills.

The paradigm shift to training the technical manager in requisite management skills is only beginning to emerge. As a result, many practicing technical managers feel ill equipped since they are strictly self-taught regarding skills needed to successfully manage. To emphasize the magnitude of the issue, research such as job satisfaction surveys has disclosed that most graduates of theatre technology programs indicate personnel management and group dynamics are among the most difficult aspects of their jobs and are singularly the one for which they feel least prepared.

Part of the confusion surrounding the need for effective management skills lies in the lack of a singular job description for a technical manager. Unfortunately, a single definition is not really possible, given that the exact duties of the individual holding such a title are very skill-and-organization specific. Rather than attempt to provide a definitive job description, this text looks at those essential qualities needed by anyone who serves in a technical management capacity within any of the performing arts and its wide-ranging related organizations and who must interact with not just things but people. Duties are examined and discussed with regard to the central theme of this book, Technical Management for the Performing Arts: Utilizing Time, Talent, and Money.

The Time, Talent, Money Triangle

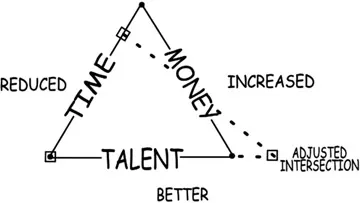

To provide strong leadership, share specific technical knowledge, and establish high expectations, every technical manager must maintain focus on the actualities of each specific production event or project. Each effort has a limit of available resources, a model that we suggest may best be viewed in the context of the Time, Talent, Money triangle (TTMT) (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Time, Talent, Money Triangle at work

The concept of TTMT is already familiar to most technical managers, even if it isn’t known by this name. The three elements identify the primary aspects of a project that need management. Most performing arts projects have rigid deadlines that emanate backwards from an “Opening (Night).” By design, this finite schedule, in conjunction with a standard 40-hour work week, creates a somewhat unforgiving demand on the TTM Triangle, although variations are possible, which makes the concept a valuable tool. Technical managers must remain mindful of time constraints and subsequently utilize their management skills to begin and sustain a successful project or production schedule. While effective management of the time portion of the triangle is critical in making a production successful, in reality most technical managers are involved in jobs that are multiproject and multiyear in scope, adding significant complexity to this responsibility.

Like the time element, the talent portion of the triangle is inclusive of all participants involved in the production process. Whether artistic director or production intern, each and every individual has talents that impact a project. Although most technical managers have minimal control over the talent pool from which they may draw, all do have the power to recognize the talent available to them, hopefully using individual talents to their best end. This means identifying each individual’s strengths and weaknesses and devising ways those talents can be best brought together.

The money portion of the triangle is identified by a lot of technical managers as their greatest challenge. Fabrication materials, skilled labor, production time, artistic talent, equipment, and facilities all cost money, so in many ways money is the most tangible of the three components. Script choices and design decisions are frequently focused on the “estimated dollar” cost of materials and performers, with little attention paid to the available pools of backstage time and talent. The truth of the matter, however, is that the money side of the triangle is probably the most easily worked. Additional money is often far easier to secure than additional talent or time.

Capital isn’t that important in business. Experience isn’t that important. You can get both of these things. What is important is ideas.

Harvey Firestone

Figure 1.2 Time, Talent, Money Triangle at work

What makes the Time, Talent, Money Triangle a uniquely useful management tool is that it is easy to foresee how any adjustment to one side impacts the other two. Conceptually depicted as an equilateral triangle, the TTM triangle closely resembles three points connected by a rubber band line. As illustrated in figure 1.2, alter the position of one vertex and there is a corresponding change in the length of two of the other sides. In order that the unaffected side remain constant, the other two sides are modified relative to the lengths of the original lengths of the sides. As an example, more highly skilled workers being compensated at above-standard wages can accomplish a similar goal in a shorter period of time.

Figure 1.3 Good, fast, or cheap

While a given problem often has numerous solutions, when modeled on the TTM Triangle, the potential solutions can be carefully analyzed and a course of action determined. For example, additional money can make possible the purchase of better materials/products, which, in turn, may reduce fabrication/assembly time. If time is tightened, more money can help compensate. However, mistakes made when using these higher-quality materials will be costlier; subsequently, it would be wise to hire the most talented artists available, thus additional money is needed. The other side of the coin might be that less expensive materials can be utilized, with excellent results, if there is a longer timeline and sufficiently talented and experienced craftspersons and technicians on the jobsite.

The Time Talent Money Triangle impacts every decision in the production process. Cynics of this planning tool often joke about the relationship of these three components (fig. 1.3): “I can give you quick, I can give you good, or I can give you cheap: PICK TWO!” The sad truth, however, is that the joke is no joke at all.

Time, talent, and money are not the only parameters affecting a technical manager. The physical constraints of the workspaces and the quality and range of res...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Meet the Manager & the Triangle

- Foundations

- Chapter 2 Roles

- Chapter 3 Authority

- Chapter 4 Personnel

- Chapter 5 Communication

- Chapter 6 Specialized Communication

- Chapter 7 Professional Practices & Resources

- Chapter 8 Employment

- Strategies

- Chapter 9 Planning & Scheduling

- Chapter 10 Analysis & Problem Solving

- Chapter 11 Budgets & Quality Control

- Chapter 12 Putting It All Together

- Wrap Up

- Chapter 13 Looking Back as We Look Forward

- Appendix I Technical Production Guidelines

- Appendix II Blueprint of a Production

- Appendix III Sample Student Job Descriptions University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Appendix IV Scenery Standards Handbook

- Appendix V Scenic Studio Safety Agreement

- Appendix VI Labor Estimation Guidelines

- Appendix VII USITT Guideline for a Standard Technical Information Package

- Appendix VIII Production Crew Evaluation Form

- Index