- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

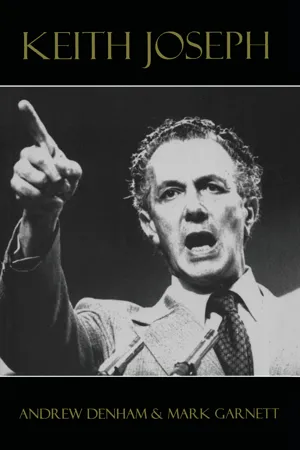

Keith Joseph

About this book

Hailed by Margaret Thatcher as the founder of modern conservatism, Keith Joseph is commonly ranked among the most influential politicians of the late-20th century. A complex and enigmatic figure Joseph was almost unique among Mrs Thatcher's senior ministers in refusing to write his own memoirs. Challenging both the "mad monk" view held by his critics and his status of mythical hero to his admirers, the authors present a picture of Joseph as a thinker and decision-maker. the authors tell of Joseph's formative years before he entered Parliamnet in 1956: the powerful Jewish dynasty into which Josph was born; his time at Harrow; at Oxford; his war years in the Royal Artillery; and his Fellowship at All Souls. This volume charts the political career of Keith Joseph. The authors challenge Joseph's self-declared conversion to Conservatism in 1974 and the importance of his "education" of Margaret Thatcher. His own ambition, intellectual integrity and consistency are all examined and a different picture emerges of his role as the intellectual driving force behind Conservative Government policy in the 1980s.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & TheoryChapter One

"Rather an Enigma . . ."

Keith Sinjohn Joseph was born on 17 January 1918. Between his conception and his birth the world which lay in wait for him underwent a dramatic and lasting change. In November 1917 a Bolshevik government was installed in Russia. Just nine days before Keith’s birth the US President Woodrow Wilson, in his “Fourteen Points”, advocated self-determination and open negotiation at a League of Nations against the old ways of secret diplomacy and hostile alliances. After more than three years of carnage in Europe the beginning of 1918 brought a mixture of fear and confidence for the opposing forces; the Germans believed that the conclusion of a separate peace with Russia would lead to a rapid victory, while Britain and its allies sought to stave off collapse until American troops arrived to swing the conflict their way. A. J. P. Taylor stressed the importance of January 1918 in world history; in that month, he wrote, “Europe ceased to be the centre of the world . . . there began a competition between communism and liberal democracy which has lasted to the present day”. That pregnant verdict was published in 1956 – the year in which Keith Joseph became a Conservative MP. More flippantly, the authors of 1066 and All That lamented this period as one in which Britain lost its status as “Top Nation” and history came to a full-stop. Joseph lived to see another major reordering of world forces, and the apparent end of conflict between the competing ideologies of 1918. But the upheavals of January 1918 produced the context which dominated his political career.1

The world crisis had a more immediate and direct impact on Keith Joseph’s family. His father, Samuel Gluckstein Joseph, was a Lieutenant in the 5th Battalion of the Royal Irish Regiment, on active service in France when Keith was born. Yet the natural anxiety of Samuel’s devoted wife Edna was tempered by her knowledge that if the child’s father never returned there would be other friends to help launch him into the new, insecure world. Keith was born in the billiard room of 63 Portland Place, the elegant home of his maternal grandfather, Philip A. Solomon Phillips. Portland Place, to the north of Regent Street, was perhaps the best example of eighteenth-century architecture in London. Phillips’ four-storey house boasted an interior designed by Robert Adam, and had been occupied between 1893 and 1898 by the author Frances Hodgson Burnett. Another celebrated literary figure, John Buchan, lived across the road in number 76, where he completed The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915); at the time of Keith Joseph’s birth Buchan was writing another novel, Mr Standfast, while serving as Director of the Department of Information and dodging occasional Zeppelin raids near his home. The Earl of Shrewsbury had his London residence two doors away from Phillips; the road also housed several diplomatic legations, and the homes of three serving MPs.2

The expense of maintaining and heating number 63 had been a constant worry for Mrs Hodgson Burnett, whose resources were also drained by the servants, carriages and horses which a Portland Place lifestyle demanded. But while Hodgson Burnett relied on her pen to support herself, Keith Joseph’s maternal grandfather enjoyed far greater security. Born in 1867, Phillips had been a partner in Crichton Brothers, a Bond Street firm of antique silversmiths. Before he reached the age of fifty he had earned enough to retire in comfort. In his later years he amused himself by examining archival records concerning Anglo-Jewish and Huguenot jewellers; this agreeable pastime resulted in several learned articles and two books. Like his famous grandson he was an assiduous (if not obsessive) contributor to the correspondence columns, and although he particularly favoured The Times he was always ready to send a note wherever he felt that his expertise might be of interest. For example, in 1929 readers of The Connoisseur were invited to share his regret that “snuff-boxes qua snuff-boxes have not so far found a historian”. Judged by his writings, Phillips was a courteous and diffident scholar. Before his death in January 1934 he had moved to an even more fashionable London address, Park Lane; his estate was valued at almost £60,000 in 1934 – comfortably over £1 million in today’s values.3

In one of Keith Joseph’s favourite novels, C. P. Snow’s The Conscience of the Rich, the narrator observes that his wealthy young friend Charles March “often envied that simplification, that compulsory simplification, which being poor imposed upon my life”.4 The circumstances of Keith’s birth ensured that he would never know that fortunate “simplification”, and it had also been denied to his parents. Samuel Joseph was born in 1888 at 50 High Street, Notting Hill.5 When Keith’s grandfather, Abraham Joseph, died aged seventy-four in 1933 his gross estate was worth £23,840. This hardly placed him at the summit of the wealth league – the net worth of the economist John Maynard Keynes in 1936 has been estimated at over £500,000 – but Abraham Joseph shared with Philip Phillips a comfortable mid-table position at a time when only the best-paid industrial workers earned as much as £4 per week. Dying within a year of each other both Joseph and Phillips were buried at Willesden, in the Orthodox section of what has been called “the Rolls Royce among London’s Jewish cemeteries”.6

Samuel Joseph and Edna Phillips, who married while the former was on leave in 1916, had no reason to fear the financial consequences of starting a family. But more valuable even than the comfortable circumstances of Keith Joseph’s parents was his inherited membership of an influential and affluent network of relatives. Philip Phillips belonged to a long-resident Anglo-Jewish family – an important consideration in itself, since refugees from the pogroms of Eastern Europe trebled the Jewish population of Britain in the three decades after 1890 and the newcomers were regarded with some aversion by the established families.7 But while Phillips had been content to assure himself of the leisurely lifestyle of a gentleman the Josephs were part of an extended and astonishing clan whose entrepreneurial drive was matched only by a penchant for inter-marriage which resulted in a highly complex family tree (p. xix).

The first member of the Joseph family to use that surname was born Coenraad Joseph Sammes in 1783. A merchant by trade, at some point he dropped the “Sammes” and changed his first name; afterwards he was known as Coleman Joseph. In the early nineteenth century his family was based in Amsterdam, then moved to Whitechapel in London’s East End. From there one of Coleman’s four sons, Keith Joseph’s great-grandfather Josiah (born Tobias Joseph), ventured into the New World. Abraham Joseph, the sixth of Josiah’s seven children, was born in Philadelphia in 1858. By 1885 he had migrated to London, and in November of that year he married Sarah Gluckstein in Paddington. Either Abraham had succumbed to an irresistible hereditary attraction or the match had been expected of him. Four of his siblings had already married into the Gluckstein family. Feelings must have been running high in 1885; earlier in that year Abraham’s brother (another Coleman Joseph) and his sister Emma had both paired off with Glucksteins.

The patriarch who supplied all these spouses was Samuel Gluckstein, who had emigrated to London from Rheinberg, Germany in 1840. For him wedlock with a Joseph was part of the natural order of things. On his first arrival Gluckstein had stayed with the Joseph family in Whitechapel. The arrangement produced a lodging-place for his heart, and five years later he married his landlord’s daughter, Hannah Joseph.8 Abraham Joseph’s wife Sarah was among twelve products of this union; they, and all the other Josephs and Glucksteins who fell for each other, were thus first cousins.

Samuel Gluckstein prospered in the tobacco trade, undercutting his rivals with cleverly advertised cigars (“The more you smoke, the more you save”). One of his enthusiastic customers was another émigré from a Jewish background, Karl Marx.9 In 1904 the main family firm, Salmon & Gluckstein (a relative by marriage, Barnett Salmon, having joined Samuel Gluckstein’s three sons in running the company) was sold to Imperial Tobacco for over £600,000 – a prodigious sum in those days. By this time the family’s business interests had diversified. In his travels on behalf of the tobacco concern Samuel’s son Montague Gluckstein was impressed by the lack of refreshment facilities for “respectable” families, who were equally repelled by pubs and by dirty cafés. In the last years of the century a chain of teashops was established, including the ornate Trocadero in Piccadilly and a branch opposite the Stock Exchange. The venture was dominated by the family although it traded under the name of a friend and more distant relative, Joe Lyons. This measure was taken because while cigar-making was considered to be a respectable trade the family’s good name might be jeopardised by an advertised connection with the dubious teashop business.10

No wistful account of London between the wars would be complete without a mention of Lyons’ teashops, with their white-and-gold façades and their waitresses (or “Nippies”) in their distinctive red uniforms. For many years the venture was a phenomenal success; by the 1930s it employed over 30,000 people throughout its various branches, which included factories producing tea and cakes. In the late 1940s the Joe Lyons food laboratory at Hammersmith hired a young research chemist called Margaret Roberts, shortly before she became the second wife of Denis Thatcher. Yet the key to its initial prosperity – the close co-operation between gifted relatives – threatened its permanence. The family already knew what might happen if personal feuding broke out, and had taken a dramatic step to guard against friction. The founder of the tobacco company, Samuel Gluckstein, was a “violent and overbearing” man whose temperament dragged the family into an extended and almost ruinous law-suit. After his death in 1873 the new partners had agreed to establish an arrangement known as “The Fund”, under which family members pooled their assets. The Chair of the company would be held through seniority rather than ability, and the proceeds would be shared on the basis of need, regardless of individual contributions. The arrangement would cover any children, as well as the adults. Even relatively trivial business decisions were to be taken only after extensive debate between the (male) members of the family.11

Stephen Aris has described The Fund as a bizarre marriage between contradictory ideologies, with “arch-exponents of the capitalist system” yoked together in something approximating to a Bolshevik Soviet.12 Alternatively it can be seen as an extreme expression of two familiar Victorian dogmas – those of self-help and of the family. Whatever the nature of its inspiration, an arrangement which guaranteed financial security could also be stifling and helped to produce some notable characters. One of Keith Joseph’s cousins, the noted painter, Hannah Gluckstein (who adopted the name “Gluck”), once exclaimed “How I hate [my relatives] with their money and general bloodiness!”. Much to the embarrassment of her conventional parents, Gluck enjoyed flaunting her non-comformity. She made no secret of her sexual orientation and “for a time turned androgyny into high fashion . .. [she] got her shirts from Jermyn Street, had her hair cut at Truefitt gentleman’s hairdressers in Old Bond Street, and blew her nose on large linen handkerchiefs monogrammed with a G”. On a theatre visit in 1918 she sported a Homburg hat and a dagger in her belt. But she learned to live with her hatred of the money, and continued to draw upon The Fund. Another cousin, Yvonne (the daughter of Samuel Joseph’s elder brother Bertie) became a well-known actress and writer after reverting to her mother’s maiden name of Mitchell. The qualities of the family are best illustrated by the career of Gluck’s brother, Louis Halle Gluckstein, who took a path which was outwardly conformist but whose inexhaustible drive to work for good causes and to earn honours marks him as the most eccentric of the lot. Gluck’s biographer has noted of the mainstream members of the family that “They earned knighthoods, CBEs, OBEs, MBEs, mayoralties and medals. They were QCs, MPs and Councillors”. On his own, Louis Gluckstein had worked his way through the whole of this list by his mid-sixties, exchanging an earlier CBE for the even grander GBE (Knight of the Grand Cross of the British Empire). In his next decade he started up a new collection, becoming in 1969 a Commendatore of the Italian Order of Merit. To round off his improbable attributes, Louis was also a man of striking appearance even in his seventies. Kenneth Baker, who encountered him in one of his less exacting roles (President of the St Marylebone Conservative Association) retained a vivid memory of Louis’s “immensely tall and stooped courtly figure”.13

When the family pact was established in 1873 Keith Joseph’s paternal grandfather, Abraham, was just fifteen years old. Although The Fund is often mentioned in books about the Anglo-Jewish business community the family (for understandable reasons) has not been anxious to publicise all of the details. But the story proved irresistible for Yvonne Mitchell, who in 1967 published a partly fictionalised account in her novel The Family. In an author’s note Mitchell made an explicit disclaimer, writing that she loved her family and that “None of its members will, I think, recognise themselves or one another in this book, for none of them, even the generations which I know, have been deliberately portrayed. There will be some similarities, no doubt, and near parallels in the story . . .”. Most authors include this type of self-denying ordinance only to break it in some places. Thankfully for the historian, Yvonne Mitchell was unusually forgetful of the restraints. There are one or two obvious fictions in the novel; for example, while Yvonne’s own father Bertie Joseph is barely disguised in the character...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Joseph family tree

- 1 "Rather an Enigma . . ."

- 2 Triumph and Tragedy

- 3 "Altruism and Egotism"

- 4 The Start of an Innings

- 5 The Man in Whitehall

- 6 "Blind"

- 7 The First Crusade

- 8 "Inflammatory Filth"

- 9 A Titanic Job

- 10 "Not a Conservative"

- 11 "A Good Mind Unharnessed"

- 12 "Really, Keith!"

- 13 The Last Examination

- 14 "If you seek his monument. . ."

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Keith Joseph by Andrew Denham,Mark Garnett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.