Approaches presented in this section do not form a comprehensive systematic analysis of different historical play theories. They rather present different disciplinary approaches, which in our mind are relevant in answering today’s challenges. The Froebelian approach in the three first chapters represents philosophical educational understanding about play: Smirnova picks up Vygotsky’s psychological basic ideas about child development and pretend play, and the playworld approach expands the cultural-historical play approach by combining Vygotskian psychology of art to play theory. The last chapter has elaborated a non-linear system model from Kurt Lewin’s analysis of social relations and Gestalt therapy practices, which reveals a system state of role relations in children’s pretend play.

Introduction

The founder and creator of kindergartens (1837) was Friedrich Froebel (1782–1852), who came to the view that play was deeply educative if supported and encouraged by adults. Play transforms from being part of childhood into work that inspires, is worthwhile and is conscientiously performed (Brehony 2016). He therefore built play into his kindergarten curriculum, at first in prescribed, adult-led ways, but as his observation skills of children at play developed he became shocked at the way practitioners interpreted the adult role. He came to trust the children more, and to realise the importance of quality in training for kindergarten teachers. This led to a more open and flexible approach to the play of children. He extended this thinking to babies and toddlers. His last work was published in 1844 with the now obsolete and misleading title ‘Mother Songs’ which were in fact for parents and grandparents, as well as older siblings, who he realised appreciate support in understanding the importance of play for tiny children, and in developing emergent play in the home context. In this chapter a Froebelian approach to play is reflected on, and just as Froebel became unsettled and troubled enough to change the assemblage (Osgood 2016: 160) of his own thinking on play, two further assemblages are presented following his setting an example in having the courage to do this in the light of new evidence through his observations and discussions with close colleagues.

The second assemblage came as a result of the way his early followers, after his death in 1852, returned to the original rigid prescriptive practices of his earlier work. His schools were closed in Saxony in 1851, regarded as revolutionary and irreligious, causing his students and colleagues to flee to different countries of the world. Bertha and Johanne Ronge in England, for example, prescriptively imposed their own interpretations of Froebelian education (Bruce 2016: 21). The Revisionist Froebelian Movement emerged which threw away the prescriptive, practical aspects of his curriculum but kept the principles of the practice (Bruce 1987, 2016). This was the result of the establishment of small kindergarten training colleges (children 2–7 years) such as the Froebel Educational Institute, at the turn of the nineteenth century. Lecturers began to draw on the work of emergent disciplines such as psychology as evidence supporting Froebelian education. Highly trained Froebel teachers rapidly became heads of nursery/infant departments in other colleges, and Her Majesty’s Inspectors (HMIs) of schools and colleges. Until then Froebelians had trained through locally based courses validated and endorsed through what became the National Froebel Foundation (NFF). This gave opportunities for middle-class mothers, with permission from their husbands, to train and found small home-based kindergartens in their homes, which husbands considered a respectable way for their wives to work. It also gave rise to very rigid practices. The nursery school movement was another important strand in spreading revisionist Froebelian practice, based on Froebelian principles. There was a shift away from the prescribed practices to an emphasis on the Froebelian principles (Brehony 2000; Bruce 1987; Bruce in Miller and Pound 2010; Bruce 2015a; Bruce in David, Goouch and Powell 2016). These pervaded government reports (Hadow 1933; Plowden 1967; Starting with Quality 1990) influenced by Froebelians advocating principles and the importance of play in primary schools

This chapter puts forward the urgent need in the UK for a third period of assemblage of Froebelian work on play, which interrogates the important issue of the role of the adult.

Towards a third assemblage of Froebelian work on play: some useful tools for a strong future

Authors in this handbook emphasise the importance of the adult role in relation to developing the play of children. At times the emphasis is on the adult creating and managing the indoor and outdoor environment with equal status. Nature, with gardens, forests and streams, has a central place in Froebelian education. Dowling (2013) describes the physical environment as the third teacher.

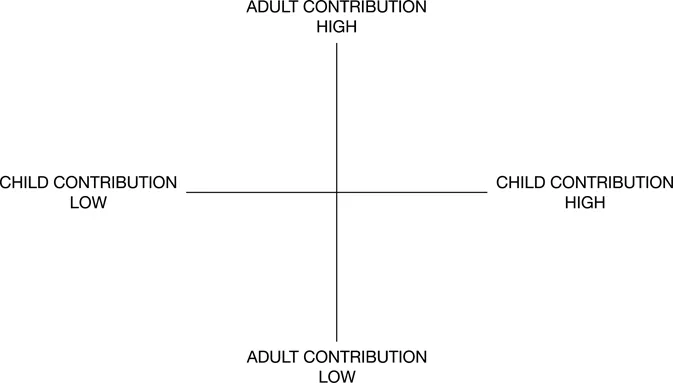

Kalliala, a Froebel-trained teacher and academic at the University of Helsinki, highlights the crucial nature of observation for Froebelians, and the need for the adult to be externally passive and internally active (Kalliala 2004). The following chart clarifies how best the adult can help children to develop their play.

The prescriptive approach, with close adherence to Froebel’s original ways of working on play, results in the adult’s contribution being high, while the child’s is low. Children are taken to the shop, the adult leading shop play on return. The opposite applies when the adult involvement is low and the child’s is high. The adult might provide shop materials after the visit, for children to indulge in ‘free play’ which is often a laissez-faire approach to play. Another approach to the adult role is ‘by the book’. The adult might tell a story and the children quite literally act it out, or sing the song and rhymes with actions correctly performed. The approach favoured by the author is interactive (Bruce and Meggitt 1996) with both adults and children making a high contribution, playing together. The interactive adult takes very seriously Kalliala’s reminder that Froebelians need to act on their observations with sensitive, moment-by-moment responses. But how?

The Engagement Scale, first developed by Professor Ferre Laevers (1994) has been widely disseminated internationally through the work of Professors Pascal and Bertram. It helps practitioners explore the emphasis they are (probably unwittingly) putting in the way they develop children’s play. The relationship between autonomy, sensitivity and stimulation is key to the adult role. Autonomy is about helping children to play independently but having a trusting relationship with adults so that they can seek out but also be given the right help at the right time in the right way. Sensitive adults are good observers, aware of how and when they are needed, and how and when they need to hold back (Smilansky 1986). A stimulating adult is also a good observer, but goes beyond supporting the play. Stimulation means that children are extended in their play, to develop what Bredikyte and Hakkarainen call mature play (Bredikyte 2011). The author of this chapter (Bruce 1991, 2012, 2015a) sees this as a process of deepening the play, so that children wallow in it, concentrate and are totally immersed in, for example, the Treasure Basket (Goldschmied, see chapter 3) or the group pretend play scenario.

Figure 1.1 The role of the adult in relation to children’s play in early childhood (inspired by Roberts and Tamburrini (1981).

The phrase ‘Observe, support, extend’ (Bruce 1987; 1997: 97) clarifies the role of the adult in developing play in early childhood and beyond 7 years into middle childhood, adolescence and adulthood.

These three tools (balancing high/low child/adult contributions to the play; the nature of the engagement of the adult in the play; and the ability to directly or indirectly teach play through bringing together the ability to observe, support and extend play) strengthen the role of the adult. This foregrounds the Froebelian tenet that children need freedom with guidance (Liebschner 1992). The balance of what this means needs reviewing. These tools offer guidance in undertaking this unsettling task.

Navigating free-flow play through twelve features (Bruce 1991)

The above tools enable reflection about the adult role in children’s play by the practitioners themselves. But more specific detail of what characterises play is needed if families and practitioners are to be supported in looking afresh at what play is all about in the world of today.

In the home situation parents and grandparents need their confidence to be built in developing play. If parents have not experienced mature, deep play themselves they will find it difficult to understand what it is, or why it is important. Once they know they become deeply committed to it (Athey 1990; Bruce 2012, 2015a; Bruce, Louis and McCall 2014). There is, in the UK, and Kalliala reports this in the Finnish context (Kalliala 2004), muddle for parents who try to be both friends and guides to their children. The issue of freedom with guidance is huge in developing home play. Swinging from laissez-faire and letting children do as they wish in totally free play to being very controlling so that play is constrained or even extinguished in favour of what is supposed to be proper learning is a real issue. Froebelians have always worked closely with families, and it can be argued that kindergartens were the first community schools.

Supporting families to develop play at home necessitates articulating what is important about play, and why it should be encouraged. Convincing colleagues, policy makers and politicians untrained in early childhood education is another challenge requiring clear articulation, backed up with evidence from research and theory. When policy makers and politicians feel unclear and unable to control events, they impose prescriptive ways, resulting in narrow schooling rather than education. The plethora of national curriculum framework documents now in many countries is the result. The English EYFS (2012) document gives surface attention to mature, free-flowing play alongside a fierce inspection regime. At the International Froebel Society Conference in Kassel (2016) the president, Professor Mathias Urban, emphasised the importance of practitioners being trained in a clear philosophical framework alongside working towards greater social justice.

In order to improve articulation strengthened with evidence about play, Froebelians urgently need to revisit their philosophical framework (Bruce in Miller and Pound 2010; Bruce in David, Goouch and Powell 2016). Osgood (2016: 159) advocates ‘unsettling received wisdom’. However, navigational tools are needed to achieve this in articulating play and embedding deep, mature play in the lives of the children practitioners spend time with and the families to whom they are committed. They contribute to ‘a set of core objectives and shared political commitments’ (Osgood 2016: 161).

Following the imposition of the English National Curriculum and Ofsted regime (1989), the author gathered together strong themes from the literature on play, which were commonly held by researchers and theorists, characterising them as twelve features of play. They have served as navigational tools for practitioners in the UK and are widely used in training practitioners on early childhood education and care courses (Bruce and Meggitt 1996; Bruce, Meggitt and Grenier 2010; Bruce, Meggitt and Manning-Morton 2016) but have also impacted on policy makers and politicians, inspectors and heads of schools. They are embedded in the legally enshrined Curriculum Guidance for the Foundation Stage (2000) and Birth to Three Matters (2002) in England and later the Early Years Foundation Stage (2008). In Scotland they are referenced in the document Building the Ambition (2014) which also emphasises the importance of training practitioners to develop play with children.

To address reliance on received wisdom regarding play, through understandable caution about leaving the safe comfort zone that accompanies what is thought to be known, the wording of each feature of play is regularly framed into a new assemblage, ‘generated through interactions and relationships with the worlds in which we are enmeshed’ (Osgood 2016: 158). New evidence arrives, and philosophy changes through the disruptive impact of postmodernism (Osgood 2016) and subsequent post-human philosophy, with current fascination of what makes dialogic spaces (Lambirth 2016). The twelve features continue to provide navigational tools in new assemblages (Osgood 2016: 158) through which to ponder mature and deep play, impacting in forward-looking ways that are practical and fit for current purpose, and opening up new worlds.

Feature one

Play feeds on real experience. It would be unethical to deprive children of normal experience on purpose, but there have been contexts (such as Romanian orphanages) that demonstrate that this constrains development, including the ability to play. Everyday life experiences provide the stuff of play. Preparing meals together, going shopping, making mud pies in the garden, planting vegetables, walking to the river, the park, catching a bus, walking the dog, seeing kittens born, playing on a bomb site … the list is endless. Children learn through their senses, their movements and through people in the cultural and community context in which they grow up. The chapter on Treasure Baskets and Heuristic play for babies and toddlers, describing the work of the Froebelian Elinor Goldschmied and those who are taking forward her work (Hughes and Cousins), demonstrates the importance of offering carefully chosen objects in the presence of a loved and significant adult.

The Froebel Nursery Research School was based in the beautiful grounds of the Froebel Institute, of which the author was head and referred to as Mrs B in the book (Athey 1990). A group of families with children from birth to five years participated. When the observations of children were analysed three-quarters of the representations children made in drawings, constructions, dances they choreographed, music they composed, subjects they told stories about, or play observed could be traced back to an experience provided in the nursery which was exerting an influence on both the free-flow play and the representations. To put this in Froebelian terms, the symbolic life of the child was linked to the first-hand real and direct experiences offered.

Feature two

Catherine Garvey (1977), who worked with Jerome Bruner, makes the case for children feeling in control as they play. In play there is no necessity to conform or bow to the pressures of external rules, outcomes, targets or adult-led ideas. Rules, in play, can be broken, created, changed and challenged. This enables children to face life, deal with and face situations, work out alternatives, change how things are done and cope with their future. Often, when they form a group as part of the adjustment before the play can flow, children will initiate games with definite rules, such as hopscotch, skipping rhymes, catch, or football as reported by the Opies (1988) in their major observational studies of street games, songs and rhymes. Onc...