![]()

PART 1

HISTORIES OF PHOTOGRAPHY

INTRODUCTION

In this part of the book we will be analysing different approaches to the history of photography. The use of the plural term ‘histories’ is intended to show how far historical writing is slanted by the ideas of different historians. Disputed ways of writing about photography are debated in Chapter 1: ‘Histories and Pre-Histories of Photography’. Historical writing may have an unreasoned bias or ‘agenda’ but more commonly historians reflect the shared viewpoints of other specialists in their area of expertise. Some historians are motivated by a desire to correct other interpretations. We have argued there is no single unified history of photography and we may need to be objective and think things through rather than accept a given viewpoint or perspective. There are, nevertheless, key issues and debates that command attention and some ‘histories’ have greater legitimacy than others.

Chapter 2, ‘Photography in the Nineteenth Century’, introduces a debate on the birth of photography and the historical context in which the new medium became established. This chapter provides a discussion of earlier inventions and practices that belong to the ‘pre-history’ of the medium. It includes analysis of socio-cultural and technical factors that relate to the discoveries in the 1820s and 1830s and discussion of various applications of the medium in the middle years of the nineteenth century. We have argued that the major technological innovations that appear in nineteenth-century photography remained largely unchanged until the digital revolution of the late twentieth century.

The central concern in Chapter 3, ‘Photographic Realism: Straight Photography and Photographic Truth’, is to encourage readers to think more deeply about the specific character of the medium and in particular to address how it compares with other systems of representation. Chapter 3 introduces a discussion of perspective in painting as a quasi-technical method of depiction that sought to eliminate or at least modify what seemed to be arbitrary and selective ways of ordering the visible world. We follow the argument that Western painting developed as a ‘quest for reality’ reached its fulfilment in the invention of photography. The implications of a causal connection between painting and photography are related to a wider discussion about the concept of realism. This in turn is followed by a discussion of what later came to be known as documentary photography.

This part of the book also maps the production of constructed photographs in the nineteenth century and the various examples of this method in later artistic and political applications. We observe how the constructed photographic image (made from multiple negatives) is a deviation from what may seem to be the vocation of the medium to tell the truth. We also note how this ‘deviation’ is related to the imperatives of realistic seeing if only as a way of challenging its effects. This part of the book is supported by case studies on camera technologies that provide historical background to the main chapters in Part 1. The case studies are also intended to show how photographic technology became easier to use and more widely available for industrial, artistic and recreational functions before the end of the nineteenth century.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

HISTORIES AND PRE-HISTORIES OF PHOTOGRAPHY

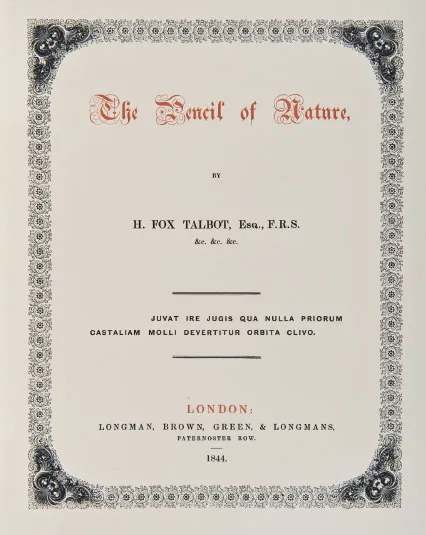

The importance of The Pencil of Nature lies in its status as the first commercial publication to include photographs – 24 paper prints pasted in by hand. Produced in instalments by the author, William Henry Fox Talbot, in the period between 1844 and 1846, it represents a major event in the history of the book. Talbot was one of the great pioneers of photography and is best known for the invention of the negative-positive process. His invention had the enormous power of making exactly repeatable photographic images he hoped would be financially rewarding. In 1844 Talbot established one of the first photography studios in Reading (about 30 miles from London).

His studio’s first project was the publication of The Pencil of Nature. It was not a commercial success but had enormous historical influence on the development of photographically illustrated books. The Pencil of Nature anticipates the value of photographic documentation of miscellaneous ‘things’ of scientific and social interest. These include buildings and monuments, botanical specimens, inventories of possessions (including books, china and glass articles etc.), and views of Talbot’s home at Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire (England). Forty copies of the original book published in London by Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans have survived and facsimile copies have been printed at later dates.

1.1 William Henry Fox Talbot, title page of The Pencil of Nature, 1844. By permission of University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections.

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this chapter is to address the question: what is photography history? A short answer would state that photography history is whatever has been said about the practice, or rather what has been said on the subject by historians, scholars, journalists or any other speakers whose voices have been recorded for posterity. We can point to key texts, mostly books, to help readers understand first causes (including the achievements of pioneers like William Henry Fox Talbot) and offer views on the ranking of key figures and deliberations on style, historical context and social attitudes as well as material conditions of the practice at a given time in its development. There is no single story of photography and opinions vary on what should be celebrated; yet there are key themes and dominant debates. The history of any subject is variable and can be designed to further particular interests and ideas at the expense of others. This has led scholars to speculate about the nature of history itself.

DISCUSSION: WHAT IS HISTORY?

We all bring some background knowledge with us. Whatever we make of the subject is determined by this knowledge but having a past is not enough. We should ask questions about and seek to discover what is important in the practice and how others have approached it. Such questions provide a way of approaching the past in a focused and thoughtful way. We wish to show that doing history involves more than merely recording facts. One of the big issues we consider is which facts are selected and why? Who chooses? Is one perspective valid when another is not? Is history a random collection of what happened or a structured narrative in which only things of importance are predominant? Again, who chooses and what is their agenda?

HISTORICAL METHODS AND IDEAS

The Historians of Photography

To say that the historical study of photography is important would be stating the obvious. Most people with a professional interest in the medium will have at least a sketchy knowledge of ‘key moments’ and ‘founding fathers’. He or she may be aware of movements, trends, technical innovations, pioneering photography institutions (including museums and schools), overlapping or related developments in other disciplines that influence our understanding of what photography is. There are of course keynote speakers and important documents, famous journals and other essential publications on photography as a mass media phenomenon or as art. The expert and the amateur have perspectives and both seek validation. The history of photography, like any history, is a site of contestation. As the photographer and photography theorist Joan Fontcuberta says: ‘Histories, like any other human product, are governed by conventions, beliefs and circumstances of time and place’ (Fontcuberta, 2004: 14).

Photography history is not only wide ranging but is constantly in dispute. When a photographer asks herself what kind of photographer she is the question is inscribed in history. Fontcuberta notes: ‘There can be no real creation without historical consciousness’ (ibid.: 12). This might be a useful starting point since questions of genre, function or professional status attaching to the practice take us directly into debates on historical method. If photography has an identity what is it? What is its ‘paternity’ and where lies its specific field? Is it wrong or misleading to look for a single cause that marks the beginning of photography and determines its subsequent history? In this chapter we argue that photography has no single history and no essence but rather has a plurality of approaches and ‘histories’ that are time-bound and adaptive to changing circumstances. Rather than constructing specific histories we will indicate some of the ways photography is historicized and indicate new approaches and ideas.

Historically photography is something of a Cinderella subject, by which we mean it is overshadowed or looked down upon. It is often seen as a component part of art history or media studies – subjects that were themselves overshadowed in the past by political and social histories. Photography forms a lesser history in the general scheme of things and yet its appearance in the academic curriculum indicates its importance in the humanities and in wider fields of scholarship.

The idea of photography as a lesser art is an old prejudice now superseded by the fashion for art photography as a powerful presence in the art market. The relative status of photography (qua art or science) is, nevertheless, a matter that historians of photography still address. The growing literature that we might define as ‘photography history’ indicates a widening recognition of the importance of a medium largely ignored by scholars in the period before Helmut and Alison Gernsheim’s pioneering historical research in the 1950s. Other important contributions to the early history of photography include classic studies such as Josef Maria Eder’s Geschichte der Photographie (History of Photography) first published 1905 (1978), Gisèle Freund’s Photography and Society of 1936 (1980), Beaumont Newhall’s The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present Day which appeared under this title in 1949, Robert Taft’s Photography and the American Scene: A Social History, 1839–1889 of 1939 (1964), Raymond Lécuyer’s Histoire de la Photographie (1945) and Aaron Scharf’s Art and Photography of 1968 (1974). Essential histories of photography published more recently include Jean-Claude Lemagny and André Rouillé (1987), Michel Frizot (1998), Geoffrey Batchen (1999), Mary Warner Marien (2002), and Steve Edwards (2006b).

BIOGRAPHY: HELMUT AND ALISON GERNSHEIM

Helmut and Alison Gernsheim co-authored The History of Photography: From the Earliest Use of the Camera Obscura in the Eleventh Century up to 1914, published by Oxford University Press in 1955. Later editions were published by Thames and Hudson. Helmut was a German Jewish émigré who became a British citizen in 1946. This huge study became a central text in the historical study of photography. Helmut and Alison’s huge collection of photographs, books, research notes and correspondence were sold to the University of Texas in 1963. The Gernsheims’ written work, together with the published works of a few other photography historians, gave the subject a more serious standing in the humanities. A Concise History of Photography by Helmut, in collaboration with Alison, was published in The World of Art Series by Thames and Hudson in 1965.

The slow rise of photography to a higher station in the social view of human occupations is related to its humble origins as a mechanical art. Compared with high cultural practices such as painting or classical music, photography was regarded as a ‘lowly carrier of information’ (Edwards, 2006a: 14), lacking scholarly content and powers of emotional expression. Histories of photography provide discussions (often disputed) based on studies of the pre-histories of the medium and often dwelling upon what came first (founding images and the mysteries of their creation) before proceeding to reflect on the questions about the identity of the new medium. Broad categories of science, technology and art have been offered in historical writing as the most obvious sites for the early discussions about the new medium of photography. In this chapter we accept the relative autonomy of photography as subject in its own right. The literary scholar Lee Patterson says of literature that it is a practice ‘whose difference from other kinds [of writing] is a matter not of its essential being but of its cultural function’ (Patterson, 1995: 256). A similar point might be made about photography. If enough people see its products as photographs it has a functional existence as a distinctive medium with a legitimate right to its own histories. The related philosophical question of whether photography has ‘essential being’ is discussed at various stages in this book (see Chapter 3 in particular).

The Making of Photography and its Histories

Photography in the nineteenth century has been characterized by some historians as a technological initiative and, as noted, much has been written about its founding discoveries and innovations in the period before its triumphal launch in the late 1830s. (The scientific and technical apparatus is discussed in Chapter 2 below). Suffice it to say at this point the making of photography and its later histories are infused with a strong sense of their progressive character as a medium often contrasted with the timeless arts of painting and drawing. For example the matter of its ‘discovery’ is still widely debated. For some historians its inception is strongly connected with industrial capitalism and a growing demand for what the art historian Steve Edwards has called ‘cheap mechanical means of producing images’ (Edwards, 2006a: 71). Edwards reflects on early industrial societies and notes ‘emerging desires’ for reproductive techniques capable of supplying ‘portraits for the new middle class and the wide range of visual documents required by the new society’ (ibid.: 71). The French curator of photography Bernard Marbot (1987: 15) argues, like Edwards, that historical forces in early nineteenth-century Europe were effectively willing photography into life. In both of these accounts the...