eBook - ePub

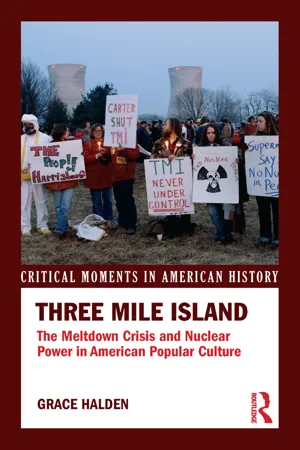

Three Mile Island

The Meltdown Crisis and Nuclear Power in American Popular Culture

This is a test

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Three Mile Island explains the far-reaching consequences of the partial meltdown of Pennsylvania's Three Mile Island power plant on March 28, 1979. Though the disaster was ultimately contained, the fears it triggered had an immediate and lasting impact on public attitudes towards nuclear energy in the United States. In this volume, Grace Halden contextualizes the events at Three Mile Island and the ensuing media coverage, offering a gripping portrait of a nation coming to terms with technological advances that inspired both awe and terror. Including a selection of key primary documents, this book offers a fascinating resource for students of the history of science, technology, the environment, and Cold War culture.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Three Mile Island by Grace Halden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER 1

Atoms for War

World War II and the Cultural History of Early Nuclear Development

Popular culture has long been a medium through which to explore moments of trauma. Popular culture was a useful way for the public to navigate World War II, especially the Holocaust and the bombing of Japan, which were considerable rupture moments in the twentieth century. Emerging from this event was the nuclear age and, again, popular culture became a useful way for the public to navigate their complex responses to the ever-changing world. For Alison M. Scott and Christopher D. Geist, atomic bombs have cast a shadow over Americans and this is explicitly witnessed in popular culture.1 There is an intimate link in popular culture between the nuclear weapon and nuclear power, often amalgamated as ‘nuclear technology’ with safety issues, ramifications, and historical significance enmeshed in one term.2 Before looking at nuclear power and the development of the Three Mile Island plant (Chapter 2), it is first important to explore the ‘twin’ of nuclear power in cultural theory—the nuclear weapon. Scott and Geist make the bold, but not inaccurate claim that “no phenomenon of major significance in modern world culture and history can be fully appreciated and examined without this new dimension”.3 This new dimension refers to the “new social history” that came from the atomic attack on Japan during World War II; this is never more true than when looking at cultural responses to nuclear power.4

It has been difficult, if not impossible, to sever the link between nuclear weapons and nuclear power. This link is something Anna Gyorgy comments on in No Nukes: Everyone’s Guide to Nuclear Power when she questions what exactly we mean by the term ‘nukes’. Gyorgy states, “Any building that contains as much radiation as 1,000 or more Hiroshima-type bombs deserves careful watching.”5 Written in 1979, Gyorgy’s text highlights the dangers associated with nuclear plants, naming human error, hardware failures, environmental damage, and natural disasters (such as earthquakes at plant sites) as chief issues. Included in her understanding of the word ‘nuke’ are plants such as the poorly performing Vermont Yankee station. A public information pamphlet from 1982, questioning the very notion of a ‘peaceful’ use of atomic technology, also begins by highlighting the association between nuclear power and nuclear weapons: “The enormous power locked in the atom was first revealed to the world in 1945. Since then this power has also been harnessed for generating electricity. But like Siamese twins, the military and civil technologies remain linked.”6

To fully appreciate the early history surrounding nuclear energy culture, we must start with the technological innovations of World War II.7 As we will come to see in Chapter 2 onwards, many of the anxieties linked to nuclear weaponry from World War II and the Cold War manifested again during the 1979 Three Mile Island crisis, especially with regards to concern over radiation, health impact, and environmental damage. In Chapter 2 we will also see how there was a concentrated drive in the 1950s towards the ‘Atom for Peace’ which helped see the development of nuclear power plants; however, before we can look at the peaceful atom we first need to examine the atom of war.

WORLD WAR II: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN NUCLEAR TECHNOLOGY, GENOCIDE, AND APOCALYPSE

Technological advancements have typified and dominated the twentieth century as evidenced by the standard ways of defining epochs: machine age, atomic age, and information age. Philosopher Hannah Arendt claims that the drive towards technology is part of the modern world: “For some time now, a great many scientific endeavors have been directed toward making life also ‘artificial’, toward cutting the last tie through which even man belongs among the children of nature.”8 The development of technology, especially during World War II, had such a profound impact on the human world, as well as the human condition, that Arendt proposes “a reconsideration of the human condition from the vantage point of our newest experiences and our most recent fears”.9 Our more recent ‘experiences and fears’ involve nuclear development and the many additional advances that are tied to this crucial innovation. Yet, the development of this revolutionary technology did not occur in a vacuum. In this section, we will explore how World War II saw the unprecedented advancement of what we might call ‘technologies of genocide’ and how the nuclear weapon, acting as a landmark example of a new type of warfare, rose out of a war characterized by industrialized killing. The development of nuclear technology during the last World War links this nuclear innovation to arguably one of the most rupturing and psychologically, economically, and politically traumatic events of recent history.

The Holocaust was a rupture event marking unprecedented mechanized mass slaughter and a new level of dehumanization. The trauma of this event resonated throughout the twentieth century as an extraordinary episode, one that American Holocaust literature scholar Lawrence Langer describes as causing “a permanent hole in the ozone layer of history”.10 The enormous tragedy of this period has caused many people, from academics to eyewitnesses, to attempt to comprehend the events of World War II artistically and critically. One notable example is Primo Levi, an Italian Jewish pharmacist who was transported to Auschwitz in 1944. Levi not only wrote numerous texts on the Holocaust (Auschwitz Report (1946), If This is a Man (1958), The Truce (1963), The Drowned and the Saved (1986)), but also many science fiction stories and essays detailing the potentially apocalyptic use of technology. Levi’s fiction expresses concern that fearsome technology would be the new threat facing humankind with similar potential for victimization and dehumanization as experienced during the Holocaust. In fact, much of the language used by Levi relating to the Holocaust and Nazi Party concentrates on concerns over how technology and artificial structures furthered Nazi goals; this was something fellow survivor Filip Müller also reflects on when he refers to “extermination machinery” and “the extermination technique”.11 Levi notes that part of the success of the Nazi regime was down to “German technological and organizational perfectionism”.12 Beyond the Nazi party, technology itself was a defining part of World War II and heralded the advent of advanced machines such as the V-2 and the nuclear weapon. Both World Wars saw the production of revolutionary technological innovations that seemed to position technology as instrumental to winning a modern war.

One of the reasons technology played such a vital role in World War II was that it enabled humans to act beyond their bodily restrictions, and this is instrumental when considering the capacity of nuclear technology in warfare because the weapon allows the military to act beyond physical limitations of hand-to-hand combat. Nuclear energy also, as we shall see, enables the power industry to move beyond traditional and finite power means (such as costly and limited fossil fuels). While remote warfare existed in early conflicts through the use of arrows and cannons, weapons like the V-2 and the atomic bomb demonstrated that World War II was characterized by distance weapons in a way no previous war was. This is something Stephan J. Kline, writing in 1985, reflects on when he argues that the construction of weapons (like guns and atom bombs) extends the human ability to kill and defend.13

Building on the potential for war technology to extend the capabilities of the human, psychologist Robert J. Lifton notes the benefit of technology as enabling distance between the assailant and the target; this distance seems to be enough to change concepts of mortality, guilt, and emotional resonance.14 The extensive range and capability of remote warfare to target large areas and groups of people from incredible distances makes “the high technology of destruction compatible with genocide”.15 American philosopher of technology, Lewis Mumford, argues that before the technological progression of World War II genocide was “restricted by the amount of hand labor required”.16 One example of the evolution from murder by hand to large structures of genocide can be witnessed in the shift in tactics by the Einsatzgruppen (Nazi special task force) who initially exterminated target groups by gunshot. It was found that mass shootings were inefficient, and Einsatzgruppen soldiers experienced difficulties committing close range murder; consequently, gas vans and chambers were implemented. Killing at a distance was found to minimize, or ease, the psychological distress experienced by killers. Mumford notes that distance weapons, like the atom bomb, enable psychological protection in a similar way.17

The Manhattan Project

The fear of the Nazis developing an atomic weapon led, in part, to the founding of the Manhattan Engineering District (otherwise known as the Manhattan Project) by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The group, formed in 1942, was tasked with creating an atomic bomb before the enemy. The Manhattan Project was not merely a small group of scientists working on the technology in a small room of a government building. The project had enormous scale with a staff of over 130,000 and funding that amounted to almost $2 billion. The Manhattan Project was spread over many sites including Canada and the United Kingdom.

The first successful demonstration of a controlled nuclear chain reaction was the Chicago Pile 1 in December 1942. The Chicago Pile was the first nuclear reactor and wa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Series Introduction

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgmentsr

- Timeline

- Preface: Nuclear Culture

- 1 Atoms for War: World War II and the Cultural History of Early Nuclear Development

- 2 Atoms for Peace: Nuclear Power and the Influence of the Long 1960s

- 3 When Science and Society Collide: The Three Mile Island Accident in Human Context

- 4 Nuclear Reactions: Three Mile Island in Popular Culture

- 5 Fears and Fallout: Three Mile Island’s Legacy, Chernobyl, and Fukushima

- Documents

- Bibliography

- Index