This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

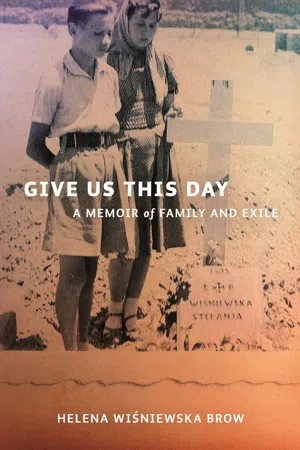

In June 1944, when 14-year-old Stefan Wisniewski stood by his mother's dusty Tehran grave, he knew his world was about to change again, forever. Give Us This Day: A Memoir of Family and Exile explores the story of one of the 732 Polish child survivors of wartime Soviet deportation offered unlikely refuge in New Zealand. Seventy years later, and no closer to a longed-for Polish homecoming, Stefan's New Zealand-born daughter revisits his past. What is the burden her father has carried all these years? And why is he unable—or unwilling—to let it go? With an aging father and the ghost of a namesake aunt as her guides, Helena Wisniewska Brow searches for meaning in the family lives shaped by exile: her father's, her mother's, and her own.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Give Us This Day by Helena Wisniewska Brow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

I’m a poor audience for my memory.

She wants me to attend to her voice non-stop,

But I fidget, fuss,

Listen and don’t,

Step out, come back, then leave again.

Wisława Szymborska, ‘Hard Life with Memory’

In May 1988, I stood on a Polish riverbank with my father and my uncle, looking at the Soviet Union. The grassy banks opposite stretched away in either direction, ending in lazy curves, one turning left, the other right, before disappearing from view. There was nothing to see beyond the murky water and the tree-covered banks: only an open early summer sky, white lumps of cloud.

‘So this is it? The Bug River?’ I asked.

‘No, the Bug River,’ my father said. ‘Bug like in boogie.’ He stretched the vowel, exaggerating it with pursed lips. ‘It’s the border. Just over there, that’s Brześć, where we lived, that way, not far. If we could get across, we could walk from here.’

I know that, I was ready to say. I know all about this town, about this river; I grew up with these names lodged in my head like unwelcome visitors. I was teasing with my silly English joke. But my father wasn’t looking at me. He’d turned to his brother.

‘Why didn’t we get a visa, Kazik?’ he said. ‘We should have got a visa, so we could go home and look. I can’t believe we didn’t get a visa.’

I stared at them. What did he mean? We had travelled as far east as we could and this sleepy river was the end of the line. Behind us was our car, its doors open to the afternoon heat and buzzing midges. I could hear my Polish uncle Wacek and his wife Jasia chatting in its back seat, waiting for us. But my father’s aquiline profile was still fixed eastwards, his eyes scanning the Russian riverbank as if willing the past to emerge from behind a clump of reed. Kazik, a darker, rounder version of his middle-aged brother, was staring too, shading his face with his hands as he looked. Somewhere out of sight and out of reach was Brześć, the pre-war Polish town that had once been their childhood home and that was now the Russian town of Brest.

The Poland we had been visiting, Poland in 1988, was a country desperately kicking its way out of the Soviet Union’s grip. Its faded cities, empty shops and sad, drab population were more than the slow-burning legacy of 50 years of Soviet domination. In the early 80s, Poland had also suffered three years of martial law; the crippled economy those years produced had sent hundreds of thousands of Poles fleeing for the west. I thought it was depressing. The rural charm of these open borderlands with their endless horizons and swaying birch trees was lost on me. Our shiny leased Renault had marked us out as strangers and the novelty of being stared at and chased by excited children when we slowed through narrow village lanes had long worn off. I’d had enough of visiting bathroom-less cottages owned by distant relatives wearing headscarves. I was tired of feeling out of place. I wanted to go home.

Home for me at the time was London. I’d been there almost two years, happily employed in the cramped Fleet Street office of the New Zealand Press Association, writing stories for the newspapers at home on football hooligans, Antipodean businessmen, retail trends and royalty gossip. It was fun. I was 25 years old and—I had to keep pinching myself—making a living doing something I liked in a city that I had once only dreamed of visiting.

‘Things always fall into place for you,’ my Wellington flatmate had said to me with surprising bitterness when I told him I’d been offered the job. ‘You’re just a lucky person.’ I knew it was a great opportunity for a rookie journalist. But there was something about being reminded aloud of my good fortune that had made me uncomfortable. I’d carried his words to London with me in my suitcase like a bad omen. So far, everything had been fine, but standing there on the banks of a river in eastern Poland, I felt them work their way into my head again. I was lucky I didn’t have a Russian visa, I thought. I was lucky that I didn’t have to go there.

Waiting for me in London was also the boyfriend who’d encouraged me to do this trip with my father. ‘You might not get another chance,’ he had said. ‘You should go.’ James and I shared a room in an attic flat near Wandsworth Common and when we weren’t working took cheap and romantic long weekends in European capitals and went to country pubs for lunches on winter Sundays. We partied as often as we could with other noisy Kiwis in bars and restaurants in the King’s Road and Covent Garden. Our aim (wasn’t it everyone’s?) was to have as much fun as possible. So I can only just remember my middle-aged father arriving at Heathrow airport from Auckland with his brother, both men still slim and brown-haired, years stretching ahead of them. I can’t remember clearly what tempted me to join them on a four-week, figure-eight loop of Poland. I recall only my fears. How would I cope with my first taste of Soviet-style communism? More scarily, how would I cope with these aged travelling companions?

Maybe it helped that my father had held his tongue about my new domestic arrangements in London. Unsurprisingly, he’d declined my half-hearted offer of a bed at our flat, booking instead an over-priced Bloomsbury hotel room that he shared with his brother. When he did visit us, climbing the three storeys of staircase to our front door, he seemed impressed. He avoided glancing at the bedroom but chatted happily to James over tea at the kitchen table, admiring the botanic prints inherited from the previous tenant on our cream walls. I knew, of course, that Dad wasn’t as comfortable as he looked. Mum had already warned me. ‘Don’t tell your father I’ve called,’ she’d said. But I hadn’t anticipated his tactful silence. Perhaps my very Catholic father had finally noticed that I’d spent the previous two years creating a new, more grown-up version of myself.

I was wrong. My father’s silence didn’t indicate a shift in the tectonic plates of our relationship. He had simply—perhaps under pressure from my more practical mother—made a decision to hold his tongue. In hindsight, it was a clever move, letting me feel like an adult: I must have decided it was time I paid my father and his story some attention. I’d spent my childhood trying to ignore the past my father obsessed about, a homesickness that he seemed unable to let go. I’d never understood what it was about the comfort and safety of life in New Zealand—and, it seemed by implication, my mother, my sister and me—that had always failed to satisfy him. Maybe, for the first time, I realised there was something I needed to know.

We left London in the rain on 10 May. The grey waters of the English Channel, viewed through the hovercraft ferry’s foggy windows, reflected my gloom. Even the shiny blue Renault my father had leased at bargain rates in Calais, the most up-to-date car I’d ever driven, didn’t cheer me. Later that night, in a hotel room somewhere off the autobahn outside Hanover, I must have opened my journal for the first time. I only just recognise myself in its neat, sloping handwriting. ‘S & K seem a little lost at the moment … I hope they snap out of it!’ I wrote, in text overloaded with exclamation marks and adjectives. In Poland two days later, Wrocław’s cobbled streets and its pastel-coloured architecture fail to get a mention and the tone of my writing is still inexplicably whiny. ‘Something is very wrong here. If it wasn’t for the kids and the sunshine it could be quite depressing! I wonder what we will do for a whole month!’

Wrocław was where we were staying for a while; it was home to Polish relatives I had never met before. I remember the jolt I felt when I met my Uncle Wacek for the first time. He was an older, sharper-featured replica of Dad and his heavily hooded eyes were an eerie blue version of my own. Wacek and Jasia lived in a small but spotless flat on the third floor of an inner-city block. This was the seedy Milan Kundera communist backdrop I’d always imagined and secretly feared: its stairwells, lined with graffiti, smelt of something unpleasant (could it be urine?) and led to streets of empty shops and blank-eyed people. There was little for sale in the supermarkets, certainly nothing familiar or appetising to me, and long quiet queues snaked out of dimly lit shop doorways. But in the evening, generous meals—rich soups, meat, vegetables, fruit compotes and yeasty poppy seed cakes—somehow appeared from Jasia’s cupboard-sized kitchen. The food was delicious.

Wacek and Jasia had three children, all grown, but it was their son, my older cousin Wojtek, who became my unofficial caretaker. He was a secondary school teacher with a scarily Slavic moustache and he spoke—luckily for me in this household of Poles—careful English. Within days my cousin had arranged a clandestine exchange of US dollars for cans of petrol and rolls of Polish złoty in a garage near his apartment. Maybe, I belatedly realised, he was the family member who had arranged the provisions for his mother’s menus. Wojtek and his wife Beata, a doctor, had two blond daughters, the youngest of whom seemed to spend most days in her grandparents’ tiny flat while her mother worked. I played with three-year-old Kasia—my lack of Polish didn’t bother her; she was happy to take my hand and chatter—while Wojtek watched. He seemed amused by our childish interaction, but I found his scrutiny unnerving. I wondered what he thought of me in my London jeans and silly, shiny lipstick.

Benek, another of Dad’s older brothers, was unwell and undergoing treatment for the cancer that would later kill him. We visited him one afternoon in Wrocław’s main hospital. I remember Benek’s grey face and the sadness of the men in the ward who watched our family reunion from their beds. I don’t remember anything else. ‘Was very glad to get out of that hospital,’ my journal tells me now, a permanent and shameful record of my youthful selfishness. ‘It stank of sick people. Six men crammed into a stark square room. And sauerkraut for afternoon tea!!’

From Wrocław, we took the car to Warsaw, with its strange and Disney-like old town, and Krąków, glamorous but drooping. And then we went east, as close as we could get to my father’s birthplace without a visa, to stand on the banks of a river and look across the murky water to where he really wanted to be.

We didn’t go to Russia on that trip. I drove our shiny Renault west, back to the sparkle and safety of London, of my boyfriend and my job. My father and my uncle returned to New Zealand.

I wasn’t aware then that I had visited Poland at a turning point in its history. It would never again be the traumatised and angry place I remembered. Poland had begun its transition from satellite Soviet state to democracy and two years later would hold its first post-communist free presidential election. Many of the people I met in 1988—people who fed me, gave up their beds for me, nudged me to marry, grow my hair, put on weight—would not be there the next time I was. But even as my life resumed, I knew something had shifted. I couldn’t forget my father’s ease in a country that was so foreign to me, his face and his voice finally like everyone else’s. Dad was looking for something in Poland and I didn’t know what. I wanted to be there when he found it.

Every time my birth is discussed, my father tells the same story.

‘When I got to the hospital after work, that’s when I saw you,’ he says, as if this is the only logical place for his story to start. I’ve given up asking how my young father, his fingernails still dirty from the pulp and paper mill, could happily make such a late arrival at Whakatane Maternity Annexe on that afternoon in March 1962. Things were different then, I’m always told.

‘Anyway, this nurse,’ he says, ‘she just put a baby in my arms like a parcel and said, “Here you go.” And so I take a look at this baby and I get such a fright.’ He has shifted to the present tense. He mimes holding a newborn in the crook of his bent arm, an awkward new father peering at his daughter’s face for the first time. Then he looks up and grins at me, his grown-up daughter, who is still listening because she likes the story and the way it makes her father so animated.

‘I just said to the nurse, “Oh no, I’m sorry, but you’ve made a big mistake, this baby’s not mine.” And then I tried to give the baby back to her.’ My father always laughs at this point, delighted.

‘Ha! So funny! I thought you were Chinese!’

It may have been as simple as the colour of my eyes: like my mother’s, mine are dark brown. My father had never known a brown-eyed blood relative, and his dark-eyed daughter would have been a shock. Perhaps, though, he saw something else. Perhaps it was a centuries-old genetic echo, a spooky reminder of one of the Crimean Tartar or earlier Mongol invasions of the rich lands that separated Europe and Asia. But all of my family history, maternal or paternal, is untraceable beyond a generation or two. For my father, it’s a history that starts and ends with his parents.

His mother, my grandmother, is spoken of with such respect by those who loved her—my father, his siblings, those who believe they owe their wartime survival to her—that the little that is known about her barely does justice to the scale of her legacy. There’s certainly very little about Stefania that’s tangible to me. Her pleasures, her sense of humour, the way she walked, her habits: all are mysteries. If my father is asked about her he speaks in generalisations, of her admirable qualities. Of course, Stefania must also have once been someone’s fresh-faced daughter, probably someone’s annoying sister, as well as my father and his siblings’ adored and brave mother. But no one remembers the names or faces of her family. All that’s known is that when my grandfather wed the blue-eyed girl with the heart-shaped face from Międzyrzec Podlaski, north of Lublin, he ‘married up’. Stefania Ostapowicz was 15 years his junior and from a family of some social standing. Józef, my grandfather, of whom more is known, was from humble stock.

Józef Wiśniewski’s family worked a small farm on the flatlands in Dobrynka, close to today’s Polish-Belarusian border. There were six Wiśniewski children, but it was Józef’s younger brother, Franek, who was to become the farmer. My grandfather, born in 1880, was more ambitious. He was a railway man, a role with some status in the days when unemployment was high and steady government jobs, particularly in eastern Poland, were sought after. He and his new wife lived what would prove to be a critical 40 kilometres south east of the Wiśniewski family land, across the River Bu...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Author’s Note

- Prologue

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Acknowledgements

- A note on sources

- Copyright acknowledgements

- Bibliography