![]() PART I

PART I

Defining Political Violence ![]()

1

Political Violence: An Overview

John Darby1

This chapter sets out to consider some of the problems that cluster around the concept of political violence, starting with an examination of the boundaries between political violence and other forms of violence. It will review changes in the patterns of political violence over the last 30 years or so, from an earlier focus on international wars to more recent challenges, including those presented by the Global War on Terror in the early years of the twenty-first century. It will conclude by exploring exit routes from political violence and the consequences of its ending through military victory or through a negotiated settlement.

Contested Terms

Existing definitions of political violence tend to be all-inclusive rather than precise. One recent definition, aimed primarily at the business community, includes ‘armed revolution, civil strife, terrorism, war, and other such causes that can result in injury or loss of property’ (BusinessDictionary). Another definition, widely used by undergraduate students, goes on to include the motivation of the perpetrators: ‘Politically motivated violence is commonly referred to by the terms terrorism, rebellion, war, conquest, revolution, oppression, tyranny, and many others. In general, it can be defined as committing violent actions against others with the intended purpose of effecting a change in their actions’ (Wikipedia).

The presumption in most definitions is that political violence includes organized violence aimed at overturning the state. Can it also be used to describe violence by the state against its political rivals? What about the use of protest by either the state or its opponents in order to provoke a violent response from their opponents? Is it a useful term to apply to violence not involving the state, but directed against political opponents or ethnic rivals, such as confrontations between republicans and loyalists in Northern Ireland, or wars with rival organizations inside their own ethnic community, such as the LTTE elimination of rival Tamil militant groups? Should the ‘fundraising’ activities conducted to finance the struggle – bank robberies, kidnapping and drug dealing – lose their imprimatur when the war ends and simply be classified as conventional crime?

Towards a Definition

So what conditions are necessary to qualify a conflict as political violence, in order to distinguish it from other forms of conflict? As already indicated, the two are far from discrete and the boundary between them is best regarded as a sliding scale located between the two extreme positions. Four propositions are suggested here. They are not definitive statements, but are intended to provoke a debate in search of a working definition of the term.

Proposition 1. Political violence’s principal activities, and key aims, are primarily expressed within an existing political entity, but they may be inspired and strengthened by international movements.

Proposition 2. Political violence involves the use of violence rather than the use of protest. The use of protest in order to provoke violence lies in the no-man’s land between protest and violence.

Proposition 3. The objective of political violence is to achieve changes in the political system rather than other forms of social change

Proposition 4. Political violence is an organized activity. Three questions will be examined to test the border between political violence and other violent activities: is political violence always conducted within a specific state, or can the term ever be applied to international conflict? Does the motivation of the perpetrators, whether it is aimed at advancing a political position or personal gain, help to determine the definition? And how can a distinction be made between political pressure and political violence?

Inter-state or Intra-state?

One important distinction between armed conflicts within a state and wars between states is that inter-state wars are more likely to end decisively in victory. Internal political violence usually produces less decisive outcomes, for a range of reasons: the combatants permanently inhabit the same battlefield; even during periods of tranquillity, their lives are often intermeshed with those of their opponents; and it is not possible to terminate hostilities by withdrawal behind national frontiers. As a consequence, political violence is often characterized by internecine viciousness rather than by the more impassive slaughter of inter-state wars.

Political violence carried out within a state’s boundaries, at its most extreme, can escalate into civil war. The distinction is one of scale and intensity. According to Toft and others, certain criteria must be satisfied for a local armed conflict to qualify as a civil war: it must be a dispute about governing the territory; at least two organized groups of combatants must be fighting; one of them must be the state; the stronger side must suffer at least five per cent of the casualties; and the war must be largely waged within the boundaries of a state (Toft 2006). More contentious is the common view that there must be at least 1,000 battle deaths a year, which appears to rule out the possibility of a civil war, however high the casualty rate proportionately, in places where the population is small, such as Fiji and Northern Ireland. Nevertheless, by all these measures, political violence is a term that is not applied to inter-state wars, but only to internal armed conflicts.

Unfortunately, the distinction between inter-state war and internal violence is undermined by a number of complications. First is the presumption by militants that their liberation struggles are actually legitimate wars. In virtually every peace process initiated since 1990, one of the preconditions required by militants for entering negotiations was the release of prisoners, in effect a claim that they are more than rebels or militants or criminals, but warriors engaged in a war. By implication, the violence preceding the peace process was a war rather than the plethora of other words – insurrection, rebellion, qualified terms such as guerrilla war or civil war – often used to describe it. For militant groups, this acknowledgement helps to provide the symmetry between governments and militants necessary for successful peace negotiations.

A second complication in distinguishing between inter-state and intra-national armed conflicts is the growing regionalization and internationalization of political violence. This partly arises from the social demography of ethnicity. Most ethnic minorities are not confined within a single nation-state and many disputes arise from a mismatch between the claims of particular ethnic groups and those of recognized states. Ted Gurr’s (1992) international study of ‘Minorities at Risk’ found that ‘of the 179 minorities identified in the survey, more than two thirds (122) have ethnic kindred in one or more adjacent countries’.2 The cases of Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia, Russians within many of the successor states of the USSR, and the Kurds and the Chinese in many Asian countries illustrate that ethnic identity often ignores the borders of nation-states. A 1991 study by the Institute of Geographers in Moscow, for example, concluded that only three of the 23 borders between the former Republics of the USSR were not disputed (Anderson and Smith 2001). It is not uncommon for minority groups to look to neighbouring countries for protection, or for neighbouring countries to make irredentist claims, thus propelling local disputes onto the world stage. De Silva and May (1991, 10) have described this process as the ‘second law of ethnic conflict, that once such a conflict breaks out, sooner or later, indeed sooner rather than later in this era of instant communications, it will be internationalized’. It is no longer realistic to regard political violence, in contrast to international wars, as a second-level threat to world order.

Political Conflict or Political Violence?

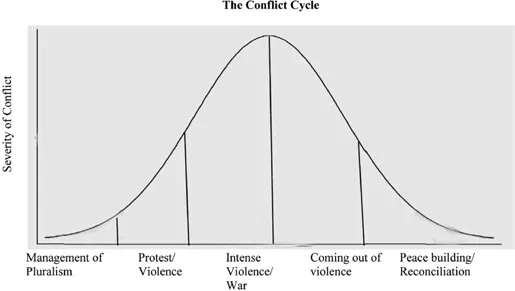

Figure 1.1 Graph to show the conflict cycle

At what point does political conflict become political violence? Consider all pluralist societies as positioned along a Bell curve, according to how effectively they deal with their component groups; the pattern might be presented as an ascending line.

At the bottom of the line are peacefully regulated multicultural societies currently experiencing little or no political violence, such as Canada and Australasia; both of these have experienced tensions, and sometimes political violence, in the past and may experience it again in the future.

Moving along the ascending line, a large number of communities suffer relatively low levels of political violence, including in the present or recent past the Basque Country, Guatemala and South Africa. In all these places violence has been conducted by organizations against the state or ethnic rivals, but has been controlled by the presence of an army or by indigenous social and economic mechanisms. If communal grievances are not addressed rapidly at this stage, violence tends to escalate and may ultimately spiral out of control into civil war.

At the top of the graph are societies in which political violence has spiralled out of control, such as those in Rwanda, Sri Lanka and Iraq. These are often characterized by open warfare conducted by organized armies. The down slope of the Bell curve is the post-violent phase of the violence cycle, following victory by one or other side, or a no-war no-peace stalemate. This is also the phase that includes the negotiation of a peace agreement and its implementation, or the resumption of violence. Permanent peace is not an attainable aspiration.

Individual societies may move along the line of the graph at different speeds. Some have completed the full course more than once, while others oscillate around one point over prolonged periods. The risk is that the violence may follow a succession of curves along the graph, as political violence rises, is suppressed or insufficiently addressed, and resumes at some future date.

It is sometimes possible, especially during the earlier phases of political violence, to address grievances and to initiate or strengthen progress towards a more peaceful accommodation by the introduction of appropriate policies. It is also possible for low-violence conflicts to be suppressed temporarily by force. But if serious grievances are not addressed rapidly, they tend to accelerate along the line of grievance and to become increasingly violent. In the absence of political reform, political violence is the default position.

Political violence enters the arena between the second and third phases of the graph. It is not always easy to draw a distinction between the more aggressive forms of peaceful protest and the beginning of violence. Are protesters against abortion clinics an illegitimate restraint on individual choice or a legitimate form of political expression? If the protest leads to violence – and at least eight people associated with clinics in the USA have been murdered since 1993, the most recent being Dr George Tiller in 2004 – does this constitute political violence? Similarly, it is not easy to draw a distinction between the state’s obligation to maintain order and its use of force. Is the use of water cannons or taser guns to control a protesting crowd a legitimate means of control or the start of a progression towards the use of political violence by the state? Despite the difficulty in drawing a firm line between them, a distinction must be made between political protest and political violence. It is the use of violence that gives political violence one of its essential features.

Political Violence or ‘Ordinary Decent Crime’?

Moser and Clark suggest that violent social and political conflicts can be classified in three different ways: economic, social and political. They conceptualize economic violence as ‘street crime, carjacking, robbery/theft, drug trafficking, kidnapping, and assaults’. Social violence represents disturbances at a more interpersonal level such as domestic violence. Political violence includes ‘guerrilla conflict, paramilitary conflict, political assassinations, armed conflict between political parties, rape and sexual abuse as political act and forced pregnancy/sterilization’ (2001, 36). They acknowledge that the boundaries between social, economic and political violence often overlap and are difficult to distinguish. Political violence is defined as ‘the commission of violent acts motivated by a desire, conscious or unconscious, to obtain or maintain political power’ (2001, 36).

This seems straightforward, almost a tautology. In practice it can be much more complicated. Consider the following case. In the late 1970s IRA prisoners in Northern Ireland engaged in a ‘blanket protest’, during which they refused to wear prison uniforms; this soon escalated into a ‘dirty protest’, during which they smeared the walls of their cells with excrement; finally, in 1980 and 1981 the protests culminated in the deaths of ten prisoners during two hunger strikes and a resurgence of support for republicans in the nationalist community. The reason for the escalating protests was the government’s decision in 1976 to withdraw ‘Special Category Status’, or political status, for prisoners convicted of paramilitary offences, and the prisoners’ insistence that they were prisoners of war and should be treated differently from other prisoners. The other prisoners were equally eager to be distinguished from IRA prisoners. They had been incarcerated, after all, for what was described ironically in Northern Ireland as ‘ordinary decent crime’. As such, the IRA prisoners denied that their actions were criminal and the ‘ordinary decent criminals’ would also have denied any political agenda.

The IRA hunger strikes and the response to them indicate how difficult it is to make a distinction between political violence and conventional criminality. Their manifestations are often indistinguishable. Militant organizations often feel justified in carrying out criminal acts to fund their armed struggle, including drug dealing (Colombia), blackmail (Sri Lanka), bank robberies (Northern Ireland), smuggling (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and kidnapping (Somalia). Indeed, there is a tendency to resort to indigenous forms of fundraising, and armed organizations sometimes follow the example of similar organizations in other countries. Consequently, the distinction between politically motivated violence and ‘ordinary decent crime’ is determined only by the intentions of the perpetrators.

Political Violence: Validity, Costs and Effectiveness

Popular attitudes to political violence are largely determined by subjective and situational variables. One perspective is that the price of political violence, as measured in human casualties, economic costs and inter-group tensions, will ultimately be higher than the grievances that led to the violence in the first place. What is the conclusion drawn by this position? Is it an argument that political violence is thus never justified because it is more costly? An alternative position holds that the continuing refusal by the state to redress fundamental minority rights, despite legitimate efforts to change the situation – through the elected assembly or the courts, through the media, through pressure from external authorities and through peaceful protest, for example – will inevitably reach a point when force is the only means available to the discontented. Again, what is the conclusion? Is this an argument that, by their refusal to reform, the state is therefore morally culpable for the violence that ensues?

Consider two examples: at the start of the twentieth century, anarchist movements in Europe and North America attempted to forcibly overthrow governments elected by popular vote; there was little dissention either internationally or nationally when various governments asserted their obligation to protect their citizens against anarchist terror by the introduction of what has been described as ‘draconian anti-terrorist legislation and the official use of torture’ (Carr 2008, 29–31). In this first case, the robust response by the state was justified in terms of ensuring the security of the population. During the 1980s and 1990s, the South African government cited a similar justification for its military campaign against the African National Congress (ANC). In this case, international reaction was more ambivalent. Many regarded the ANC campaign, especially following the introduction of apartheid, as partially or wholly justified by the intransigent and undemocratic nature of the South African government. Who was guilty of political violence here – the state that maintained its minority control over a majority by systematic discrimination under the apartheid system or the militants who resisted the state by a campaign of force? Despite the use of force by the ANC, the global community was sufficiently exercised by the innately discriminatory nature of the South African state to impose sanctions.

What factors determine ...