![]()

Chapter 1

From Greenock to London: 1868–86

Hamish MacCunn grew up in the Scottish port city of Greenock, located at the mouth of the River Clyde about 25 miles northwest of Glasgow, surrounded by the landscape that inspired some of Scotland’s most popular litterateurs, including Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott. From his home minutes away from the Clyde, he saw sweeping views of the expansive shoreline of Greenock and the distant Highlands daily; and family holidays to the Isle of Arran, the Isle of Bute, and the Highlands were frequent. Glasgow became the “Second City of the Empire”1 in the 1880s, eclipsing many of the formerly bustling port cities, including Greenock, as trade along the Clyde diminished. By this time, Greenock’s wealthy middle-class society had established a thriving cultural life with libraries, music and art societies, and two newspapers.2 Like much of Britain, and despite the flourishing urban culture, the region had no full-time professional orchestra at the turn of the twentieth century, and touring companies provided the only professional opera and ballet performances. The few performing groups that did exist were amateur choral and orchestral societies.3 With limited musical opportunities at home, MacCunn moved to London at the age of 15 to study at the RCM. He never lived in Scotland again, though he would visit often.

The MacCunn family

MacCunn’s parents, Barbara Dempster Neill and James MacCunn (see Figures 1.1 and 1.2),4 both came from influential families, members of whom served in various local government posts and prospered in two of Greenock’s main trades: the shipping industry and sugar refineries.5 The MacCunns backed two of the earliest sugar refineries in Greenock in the last half of eighteenth century, and the Neills were shipping agents and owners in the late 1840s and early 1850s. Yet it was through the shipowning business that the MacCunn family built their wealth and stature, while the Neills made their name by founding the Neill and Dempster Sugar Company. The MacCunns’ ships included brigs, barques, and vessels ranging from 170 to 1,630 tons, but their China clippers (Guinevere, Sir Lancelot, and Geraint) were their most lucrative and famous. For a time, Sir Lancelot held the record for the fastest passage from Foochow, China, to the Lizard in Cornwall.6 The Neill and Dempster Sugar Company, founded in 1853, became the Neill, Dempster and Neill refinery when Barbara’s eldest brother, John Neill, Jr., joined the firm almost ten years later. After the first refinery burnt down in 1865, the family ran the old Cotton Mill until they built a new, larger refinery in 1868, which continued under the family name until at least 1901.7

Figure 1.1 James and Barbara Dempster Neill MacCunn (date unknown). Used by kind permission of the Greenock Burns Club

Figure 1.2 Barbara Dempster Neill MacCunn (date unknown). Used by kind permission of the Greenock Burns Club

The MacCunns greatly benefitted from the Greenock shipping boom in the 1850s and 1860s. When he died in September 1873, MacCunn’s grandfather, John, owned five properties in Greenock, including the family home, rental properties in Gourock and Bridge, and ships (or shares thereof) worth approximately £22,000.8 Just after John’s death, MacCunn’s father, who had grown accustomed to a comfortable lifestyle, relocated his family to a grand Clydeside home with spectacular views of the harbor and looming Highlands.9 After only a couple of years, the family moved in with James’s mother before they all relocated into a new, more affordable stone villa christened “Thornhill” in 1877.10 The shipping industry in Greenock had been on the decline since the 1860s, bottoming out in the 1880s with the Harbour Trust of Greenock, for which James had been appointed traffic agent in 1886, becoming insolvent in 1888. Despite gaining two properties in 1886, James declared bankruptcy early in that year and closed his shipowning company. Sir Lancelot was sold, and, by 1887, no MacCunns in Greenock owned commercial vessels.11 The opening decade of the twentieth century would see the family relinquish their permanent ties to Greenock and scatter throughout the Empire (see Chapter 6).

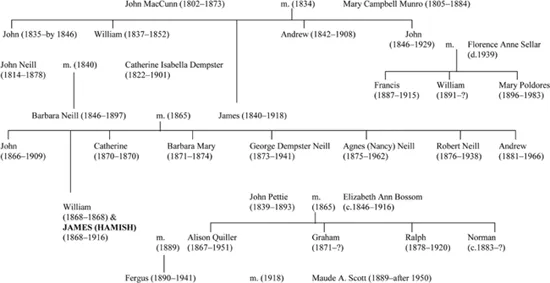

The MacCunns had nine children in all, only five sons and one daughter survived to adulthood (see Figure 1.3). MacCunn and his twin brother William were born on 22 March 1868, though William died six months later.12 Growing up amidst familial wealth provided MacCunn and his siblings with a rich cultural environment (see Figure 1.4). His parents were accomplished amateur musicians and artists.13 Barbara was “an extremely able amateur pianist” who sang “charmingly” and studied with William Sterndale Bennett.14 As MacCunn fondly recalled:

Figure 1.3 MacCunn Family Tree

[she] seemed to know instinctively the more secret meanings of the beautiful in music: and I have seldom, if indeed ever, met anyone in whom a remarkable grace of countenance and mind was so intimately blended with a keen appreciation of the appeal of music’s rhetoric and eloquence.15

The creative interests of MacCunn’s father encompassed music, writing poetry, sculpting, and inventing things “from flying machines to paper clips” (he has two patents in his name).16 Though he worked in the shipping industry, his artistic inclinations dominated his life. James’s niece, Mary, claimed that he “was the only one of my relations who could draw and I remember poring over a thick sketch book, full of careful pencil drawings which he made on board ship on a voyage to China.”17 In addition to playing the guitar and singing, he took up the cello around the time MacCunn started composing, possibly to expand the growing family’s arsenal of musical instruments. His writing included song texts and at least four librettos for his son’s choral-orchestral works. In spite of his diverse interests, Mary referred to him as “a remarkably dull man” and called MacCunn “the one really distinguished member of the family.”18

Figure 1.4 James (Hamish) MacCunn (date unknown). Used by kind permission of the Greenock Burns Club

Though he jokingly described his schooling as consisting of various people telling “me things which I was slow to understand,”19 MacCunn’s education was thorough and provided him with a firm foundation in literature, history, and Scottish culture.20 It is not known what kinds of music the family performed, but Scottish folksongs likely appeared alongside classical masterworks in family music-making. James loved Scottish literature, particularly the works of Burns, James Hogg, and Scott, and passed this passion on to his son.21 MacCunn enjoyed reading William Allingham’s The Book of Ballads, a tome he cherished during his childhood and which provided inspiration for two of his overtures (see Chapter 2) and his final choral-orchestral work (see Chapter 7).22

Like most children of the upper middle class, his musical studies began at a young age with MacCunn playing the piano by the time he was five.23 A contemporary article noted that his earliest musical education was undertaken by his parents, who apparently imposed a rigorous daily practice schedule.24 When his formal studies began, one Mrs. Liddell taught him piano, encouraging him with oranges and sweets; he studied violin with Thomas Calvert, the musical director of the Greenock Theatre Royal;25 and, around 1880, he started lessons in piano, harmony, organ, and composition with the town organist, G.T. Poulter.26 Later in his life, MacCunn bragged about writing his first composition, a piano piece, at age five. He played up the distracting influence of his beloved Scotland on his early endeavors, explaining that an oratorio he started in 1880 (likely when he was studying with Poulter) “wouldn’t ‘orate’” because he “was much more keen on sailing about Rothesay Bay, or fishing for trout in Arran, and around Arrochar.”27 While MacCunn emphasizes the Scottish locales of his youth, he never discussed his musical activities beyond listing his teachers.

London played an important role during his upbringing, though MacCunn rarely mentioned childhood events outside Scotland. At the age of eight, he spent a season in Sydenham where he heard Sir August Manns’s orchestra every day at the Crystal Palace concerts.28 Indeed, during the height of the family’s commercial success, they seem to have spent a lot of time in London, including several months of 1871.29 The cultural opportunities the capital afforded were not lost on MacCunn and his siblings, though they were not absent back home, either; while living in Scotland, the family attended concerts in Edinburgh and other nearby cities.30 MacCunn recognized the value of his “unusually advantageous ‘beginning’” and “the most sympathetic musical atmosphere” of his childhood, openly acknowledging the encouragement of both of his parents.31 Jeanie Deans, his first opera, was dedicated to “my most dear mother,”32 and, in a public speech in Glasgow, he spoke of “the inestimable benefit he owed to the enthusiastic support of his father.”33

MacCunn’s early compositions

Songs, choral pieces, piano works, and duets for piano and cello dominate MacCunn’s early output, and all reveal the influence of the Classical era as well as glimpses of his more advanced musical style (see Appendix 1). With the exception of one orchestral piece, all of his surviving early works were written for voice, cello, or piano—unsurprisingly, ...