This is a test

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Hannah Cowley (1743–1809) was a very successful dramatist, and something of an eighteenth-century celebrity. New critical interest in the drama of this period has meant a resurgence of interest in Cowley's writing and in the performance of her plays. This is the first substantial monograph study to examine Cowley's life and work.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Celebrated Hannah Cowley by Angela Escott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 ‘FEW BETTER COMEDIES THAN HERS’1

Mirth is our Deity, if we do but laugh, no matter how.2

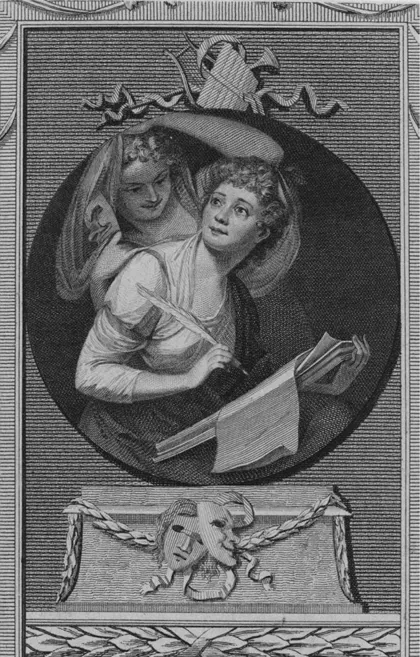

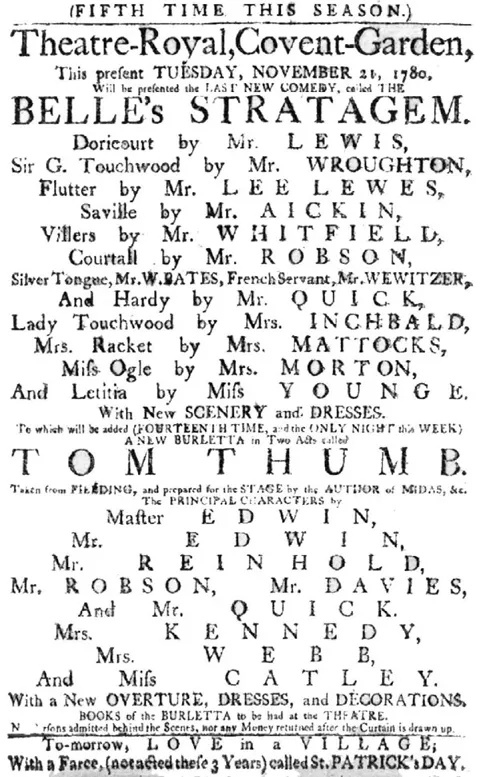

Cowley was celebrated for her dramatic comedy and associated iconically with the genre. She was identified with Thalia, the comic muse, in a portrait entitled COMEDY unveiling to MRS COWLEY (1783), painted by Richard Cosway and published as an engraved print by Mr Heath (see Figure 1.1). And she was also associated with Thalia by a ‘Gentleman of acknowledged genius’ in the prologue to Which is the Man? (1782): ‘Call’d forth Thalia’s standard to display, / And here maintain her sov’reign comic sway’. Cowley is one of the most celebrated figures of the period in comedy.3 Performance records indicate that she achieved remarkable commercial success with her works. Stratagem is listed among the twelve most frequently acted mainpieces between 1776 and 1800, only five of which were new plays.4 It was first staged at the Theatre Royal Covent Garden in 1780, with Elizabeth Inchbald as Lady Touchwood and the successful comic actress Elizabeth Younge in the principal role of Letitia (see Figure 1.2). As Anna Seward said, ‘there were few better comedies than hers’.5 Her comedies Bold Stroke and Which is the Man? were received with great applause, as recorded in the Lady’s Magazine, and the same magazine noted her high productivity over a short time: her ‘Prolific muse has given birth to a large number of dramatic offspring, within the same length of time, than any dramatic author of the present century’.6

Cowley engaged with the range of comic forms and was inventive in her favoured genre, trying her hand at a number of different types: a ‘country house’ comedy, Runaway., a partly sentimental, topical exploration of ‘manliness’, Which is the Man?; an ‘intrigue’ comedy set in Spain, Bold Stroke; a satire of quacks and lawyers, with a plot device from Molière, More Ways; an adaptation from Aphra Behn, Greybeards; an employment of Goldsmith’s successful ‘stooping to conquer’ plot device in her most popular play, Stratagem; and a dark city comedy which portrays a female creative artist, The Town, her final play. She was praised for the originality of her comedic structure in giving equal importance in her plays to both plots, ‘each … reflecting light on the other’: ‘Mrs Cowley has … boldly struck out a line of her own, and, from her very extraordinary success, may be fairly-styled the mistress of a new school’.7

Figure 1.1: Comedy Unveiling to Mrs Cowley (c. 1784), by Richard Cosway; reproduced with permission of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 1.2: Playbill of The Belle’s Stratagem, 1780. Source: Royal Opera House Collections; reproduced with permission of the Royal Opera House.

The distinctiveness of Cowley’s work was thus recognized by critics, and she herself reflected on the nature of comedy in the prefaces and prologues to her plays. Her models were Shakespeare, Congreve, Farquhar and Cibber, but she also turned to female playwrights Behn and Centlivre for source material. She was the first professional woman dramatist to use as direct sources the works of other professional female playwrights.8 Her own comedy was of its time. Moving beyond the sentimental comedy of Frances Sheridan, she wrote predominantly in the style of laughing comedy. This was a term coined by Goldsmith, as the antithesis of sentimental or genteel comedy.9 It signified ‘critical’ comedy that ridiculed vice and folly, having its origin in an English comic tradition of previous centuries. Goldsmith believed ‘Comedy should excite our laughter by ridiculously exhibiting the Follies of the Lower Part of Mankind’.10 Sentimental comedy remained more popular in the closet, while laughing comedy was more successful on stage, especially in the 1770s and 1780s when Cowley was writing drama.11 The epigraph above, from a letter by Cowley, underlines her belief in the importance of humour to comedy.

One of the challenges of reading Cowley is to observe how she tested the comic form in gendered terms, at a time when women writers were restricted by confining perceptions of women, to make critical comments about society and about their own lives.12 This chapter begins by examining Cowley’s engagement with contemporary debates about comedy and her argument for its artistic status as a genre. The ways in which Cowley exploits comedy to introduce questions of gender are examined in detail, and her challenges to the boundaries of the genre are explored. The chapter looks at the opportunity that New Comedy’s structure, with its closure in marriage, gives Cowley to advance her views on companionate marriage between intellectual equals. At the same time this structure enables her to place her female characters in a strong position to organize their own marriages, at the centre of the action of the plays, orchestrating the plots. It also finds moments when she disrupts this structure by leaving strong female characters without a partner. It examines how Cowley uses satirical humour in comedy’s traditional structure of comic disruption – levelling and inversion which end in order and closure – to reflect further on aspects of gender, on bon ton society and social class. Finally, the chapter shows how Cowley tests what might be seen to be the limits of the genre, to the extent of risking censorship, by criticizing political practices.

Hannah Cowley’s Theories of Comedy

Cowley reflected upon the genre in which she achieved her greatest commercial success and defined it at the culmination of her career as a dramatist. Having early associated herself obliquely with Shakespeare’s depiction of character, she later invoked the great comic dramatists of the Restoration and early eighteenth century – Congreve, Farquhar and Cibber – as she sought to define what she had tried to do in comedy. That she had firm ideas about the aesthetic qualities, classification and definition of mainpiece comedy, by the end of her career is seen in her definition of ‘TRUE COMEDY’ in the advertisement to Turkey – ‘a picture of life – a record of passing manners – a mirror to reflect to succeeding times the characters and follies of the present’ – and in her combative preface to The Town.13 She lamented the present state of drama in which enlarged theatres, new lighting effects and scenography, and a wider social range of audiences were responsible for the domination of gesture and spectacle over language and ideas: ‘strong muscles are in greater repute, and grimace has more powerful attraction’. She refers to comedy as ‘new class’d’ and ‘torn from its genus’, and now demanding ‘neither genius or intellect’. The preface argues for a didactic function to comedy, achieved through a combination of verbal wit and sensibility:

The patient development of character, the repeated touches which colour it up to Nature, and swell it into identity and existence (and which gave celebrity to CONGREVE), we have now no relish for … LAUGH! LAUGH! LAUGH! is the demand: Not a word must be uttered that looks like instruction, or a sentence which ought to be remembered … I invoke the rising generation, to correct a taste which, to be gratified, demands neither genius or intellect; – which asks only a happy knack at inventing TRICK. I adjure them to restore to the Drama SENSE, OBSERVATION, WIT, LESSON! And to teach our Writers to respect their own talents.14

Cowley’s emphasis here belies the nature of her successful work, particularly her earlier plays, which are not overtly moralizing or excessively sentimental, and which frequently lampoon the sentimental. The preface to her posthumously published Works of 1813 similarly emphasizes the didactic aspect of comedy, speaking of Cowley ‘holding up Vice to laughter in her Comedies’ and of ‘The Mind’ being ‘rectified by the knowledge of the World dramatic compositions convey’.15 The seriousness with which she views dramatic comedy is consonant with theorists of her time. In ‘An Essay on Comedy’ (1782), B. Walwyn argued for the importance of the genre as equal to tragedy, for ‘human nature has the same feeling – whether in a drawing room, or senate’. As Wylie Sypher has suggested, theories of comedy can oversimplify ‘a situation and an art more complicated than the tragic situation and art’, and he asks of Shakespeare’s works: ‘are not many of the problems raised in the great tragedies solved in the great comedies?’16

While Cowley drew on laughing comedy, as the epigraph to this chapter suggests, she disliked the slapstick and exaggerated gestures required from actors in the enlarged patent theatres. From the beginning of her career Cowley believed that verbal wit, ‘the bewitching dialogue of CIBBER, and of FARQUHAR’ were essential to good comedy.17 In an effusive dedication to Garrick, she praised him for his removal of slapstick from the stage:

‘tis to Mr. GARRICK the English Theatre owes its emancipation from grossness, and buffoonery – that to Mr. GAKRICK’s Judgment it is indebted for being the first Stage in Europe. (Dedication to Garrick before Runaway).

If she disliked exaggerated physical humour, Cowley nevertheless believed from the beginning that staging and physical performance were essential to drama, as was intelligent acting: ‘Actors … give impressions of character and situation with more expedition and certainty than can be done by Words alone’.18 If she regarded good acting as essential to bring to life her words, Cowley also believed that it was her responsibility to write ‘situations to attach’, in which the audience could identify and empathize with the characters, as well as lively incidents, or ‘events’ which brought ‘vivacity’ in the theatre.19 And in addition to providing action, she considered subtle character portrayal to be important, as seen in a poem of homage to Fanny Burney:

What pen but Burney’s then can sooth the breastWho draws from nature with a skill so trueIn every varying mode it stands confestWhen brought by her before th’enquirer’s viewA power – peculiar, all her portraits fill …it asks no mighty skillMisers to paint, or mad, or wayward menBut human nature in its faintest dyeBurney detects, drags it to open day20

The broad strokes and the stereotypes require little skill, Cowley believed; Burney instead specialized in the subtle character traits that escape notice. And Cowley was proud of a ‘learned’ critic’s praise of her own character portrayal: ‘When Mrs. Cowley gets possession of the spirit and turn of a character, she speaks the language of that character better than any of her dramatic cotem-poraries [sic]‘. This, I confess, I hold to be very high praise; and it is to this very praise, which my cotemporaries resolve I shall have no claim. They will allow me, indeed, to draw strong character, but it must be without speaking its language.’21

Another tool of comedy that she commanded, unusually for a female dramatist, was satire. The ironic wit to be seen in her farce, but also scattered throughout her comedies, aligns her with Samuel Foote, ‘Hogarthian caricaturist’,22 and even Ben Jonson in her more vitriolic portraits. Cowley early acknowledges the contribution of satire to comedy; in her prologue to Dupe she speaks of learned men who

fill their bold, satyric page With petty foibles – Ladies faults – Who still endure their rude assaults;

Cowley begs leave ‘To laugh at those same learned Men!’23 Cowley’s particular brand of s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Sources

- List of Abbreviations

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Few Better Comedies than Hers’

- 2 ‘The Thwarted Passions and Lofty Grandeur of Tragedy’: Cowley’s Gothic Drama, Albina

- 3 Civic Virtue, Despotism and the Fall of Empires in Cowley’s Tragedy, the Fate of Sparta

- 4 Afterpiece Experiments: Oratory, Pedantry and Politeness

- 5 The Imperial Project: Resistance and Revolution in Cowley’s Oriental Musical Comedy

- 6 A Female Sculptor and Connoisseur: Artistic Self-Fashioning and the Exposure of Connoisseurship, Collecting and Concupiscence

- Appendix: Chronology of Plays by Hannah Cowley

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index