![]()

Rich Democracies, I

Economy, Work, and Class

PREMODERN PRELUDE

As everyone knows, humans did not always live in the kinds of societies most people live in today. For the vast majority of human history and prehistory, humans survived entirely by hunting and gathering. Hunter-gatherer societies were small (usually comprising no more than a few dozen members), had a very simple division of labor (men did most of the hunting and women most of the gathering), and limited technology (e.g., spears, bows and arrows, traps). People moved around a lot, sometimes every few days or weeks, sometimes only three or four times a year. This depended to a large extent on how abundant resources were in a given place and on such things as seasonal changes.

Then about 10,000 years ago, the earliest forms of agriculture began to emerge throughout much of the world. People began to settle down and live in villages, which were permanent or semipermanent. These earliest agricultural societies are best called horticultural societies, which are societies that depend on the gardening of relatively small plots of land, using simple tools such as digging sticks or hoes. In horticultural societies women do most of the cultivating, although men usually prepare the land so that crops can be planted. The simplest horticultural societies usually possess a lot of land, so they tend to cultivate a garden for only a few years and then abandon it, moving their garden somewhere else. But as populations grew over thousands of years, land became increasingly scarce and people could not be so casual about cultivation. They had to cultivate any given plot of land for a longer time and move their gardens less often.

Sometime after 5,000 years ago, the plow was invented, allowing people to farm the land more intensively and to cultivate larger plots. More food could be grown to feed more people, which was essential because there were many more people living on the planet. We call societies that use the plow agrarian societies and the people who do the plowing peasants. In these societies most peasants live at a subsistence level, although there are often peasants who may be fairly well off, that is, “rich” peasants. Peasants face a major problem with not only getting enough food to eat for themselves but satisfying the demands made on them by landlords. Where there are agrarian societies, there are always peasants, and there are always landlords. If peasants are lucky, they may own their own land, but if they are not so fortunate, the land is owned by a landlord, and they are considered mere renters or tenants. In any case, landlords exert a lot of control over what peasants can do. Even if landlords don’t own the land, they control it, and they can use this control to exact concessions. Peasants usually must produce enough to turn over part of their product to the landlord, and they often have to provide labor services by working on the landlord’s own land part of the time. Landlords get rich, and peasants stay poor—at least, this is what happens most of the time.

In some areas of the world there is not enough rainfall to sustain agriculture of any type, and peoples living in these dry regions have taken to depending only (or at least primarily) on stock raising, that is, animal herding or pastoralism. Animals raised for food, such as sheep, goats, or cattle, cannot be eaten very often because they are capital investments. People therefore live principally on animal products, especially milk and its processed forms, such as cheese. They may also bleed their animals periodically and drink the blood. When animals die a natural death, they will be eaten, and occasionally a healthy animal will be sacrificed.

But there is another way to make a living—by buying and selling goods. Craftsmen can make goods, and merchants can buy them and sell them to someone else at a higher price than their cost. In order for these things to be possible, a society has to have a market, or a set of rules and procedures for economic exchange. Hunter-gatherers have been found to practice very small-scale trade, but they don’t have markets, and small-scale horticulturalists don’t either. Some more advanced horticultural societies have long had them (for example, in the Andes before the Spanish conquest in the early 1500s and in West Africa), but markets didn’t really get going until the rise of agrarian societies. Merchants are the key figures in markets; they buy, sell, and trade. In the earliest markets goods were traded locally or within relatively small regions. But gradually trade expanded to larger regions, and different world regions became linked to each other in long-distance trade networks. Eventually, after several thousand years, the stage was set for the development of modern societies.

When did modernity begin? Most sociologists would say it was during the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, after which people began to work in factories or offices. This makes modern societies no more than two hundred years old at the most. However, the major features that we associate with modern life did not really develop until the twentieth century. As late as 1900, the majority of people were still working in agriculture rather than in factories or offices. People drove not cars but horses and buggies. Most people did not have telephones, and televisions and modern conveniences like automatic washers and dryers, refrigerators, and electric vacuum cleaners were still decades away. Electricity was relatively new, and many people did not yet have it. And the standard of living was very low compared to today. But over the twentieth century, the most developed societies became rich, and they became democracies. This chapter and the next tell the story of the rich democracies and how they got that way.

BEING AND BECOMING A RICH DEMOCRACY

A rich democracy is a modern society with very high levels of social and economic development, along with a democratic mode of governance. Here we discuss the social and economic side, leaving the democratic side for the next chapter.

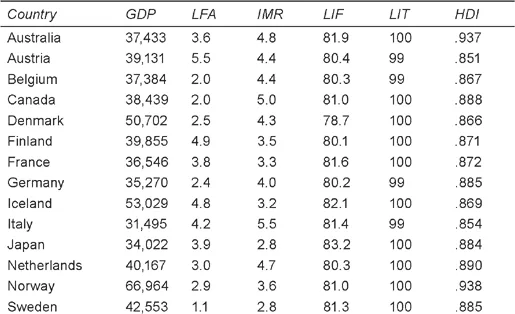

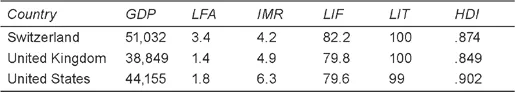

A society’s level of economic development can be measured in a number of ways, several of which are shown in Table 1.1: the level of economic productivity as assessed by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, the percentage of the labor force working in agriculture (LFA), the infant mortality rate (IMR), life expectancy (LIF), and the level of literacy (LIT). GDP is the total value of goods and services produced by a country per person per year. There is also a composite measure known as the Human Development Index (HDI), which is a weighted average of life expectancy, educational attainment, and GDP.

The first column of Table 1.1 shows per capita GDP levels for countries that qualify as rich democracies. All of these numbers are extremely high. Most people have a great deal of disposable income and can actually be considered rich by the standards of previous centuries. Even people who live below an officially designated poverty threshold have much more than the vast majority of people in these earlier times.

Table 1.1 Characteristics of Rich Democracies

Legend: GDP = Gross Domestic Product per capita calculated in US dollars (2008); LFA = percentage of the labor force employed in agriculture (2004–2010); IMR = infant mortality rate, calculated as the annual number of deaths of infants in the first year of life per 1,000 infants born (2009); LIF = life expectancy at birth (2010); LIT = percentage of the population age fifteen and older that is literate (2008); HDI = Human Development Index, a weighted average of life expectancy, educational attainment, and GDP (2010).

Sources: HDI and LIF from United Nations (2010); IMR from Central Intelligence Agency (2009); GDP and LIT from World Bank (2011); LFA from Central Intelligence Agency (2011), World Resources Institute (www.wri.org).

In rich democracies only a tiny number of people make a living from farming, with a low of 1.1 percent in Sweden and a high of 7.0 percent in New Zealand (the average in the table is 3.8 percent). Most people work in factories or offices; they manufacture things or sell people a wide range of services. People also live a long time, in most cases more than eighty years (in the case of women, about eighty-five years). The main reason is advanced medical care and lifesaving drugs, but good prenatal care for pregnant women is also important.

The infant mortality rate is the number of infants who die in the first year of life for every 1,000 infants born. We can see from the table that Sweden and Japan have extremely low infant mortality rates, in both cases 2.8. This means that only 0.28 percent of infants die in their first year. In the United States infant mortality is 6.3, which amounts to just 0.63 percent of infants dying in their first year. These are extremely low numbers when we consider that the United States in 1850 had an infant mortality rate of approximately 160 (16 percent of infants dying in their first year). In terms of literacy, in rich democracies virtually everyone can read and write.

The Human Development Index (column six of Table 1.1) provides an overall view of the extent to which any society is a rich democracy. It was constructed by the United Nations and intended as an indicator of a society’s overall level of well-being.

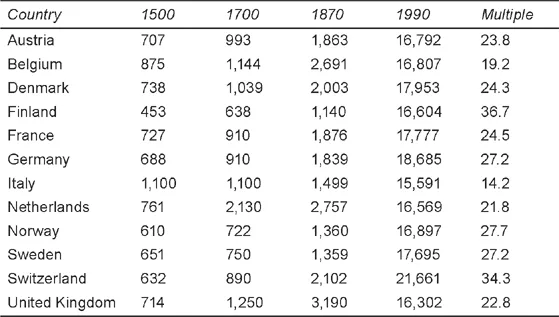

A deeper understanding of modern rich democracies can be gained by looking at them in historical perspective. After all, today’s rich democracies not so long ago were neither rich nor democratic. Table 1.2 shows per capita GDP levels for twelve current rich democracies from 1500 to 1990. The figures are all given in 1990 US dollars, which allows inflation to be taken into account. It can clearly be seen that in 1500 today’s rich democracies were poor, in 1700 they were only slightly better off, and in 1870 they were still far from rich. It has mainly been in the twentieth century that today’s most developed countries became the highly developed, affluent countries they are today. The last column in Table 1.2 shows the multiple of 1500 GDP and 1990 GDP. The numbers indicate how much wealth has multiplied over those five centuries. In 1990 these countries had between 14 and 37 times the national income they had in 1500, the average being 25.3. Rich democracies indeed!

Table 1.2 Long-Term Economic Growth in Twelve Rich Democracies

Note: Figures are given in constant 1990 US dollars.

Source: Maddison (2010).

How is this massive economic growth over the past five centuries, often referred to as “the Rise of the West,” to be explained? There is no widely agreed upon answer to this question. My own interpretation emphasizes a combination of geography, feudalism, the presence of autonomous towns, a particular type of interstate relations, and a long-term commercialization trend (Sanderson 1994).

Europe was highly favored by its geography. It was a relatively small continent that had the Mediterranean at the southern and eastern ends, the Atlantic to the west, and the North and Baltic Seas to the north. The presence of large bodies of water favors trade, especially maritime trade, which is much more efficient than overland trade. Much more can be traded, and much more wealth can be created.

Europe also had a political system known as feudalism, in which there was really no central government. Feudal lords had limited power over limited territories. This decentralized political system encouraged commerce and the growth of towns because highly centralized bureaucratic states tend to constrain commerce. Europe’s towns became highly autonomous. And during the long period of feudalism, usually known as the Middle Ages, a lot of commercialism developed. Trade and markets expanded. By the sixteenth century, Europe had developed a market economy that was on the verge of breaking out into something on a much larger scale.

Europe was also favored because it consisted of many small countries that competed with each other. Actually, many of these countries had not yet become unified states; what became Germany was a collection of small states and bishoprics until 1871, and Italy was divided into hundreds of very small city-states. The Netherlands was composed of seven provinces, the largest being Holland. And Switzerland had several dozen cantons. In any event, economic competition in Europe was fierce, and such competition was highly favorable to economic growth.

These were important preconditions favoring the development of capitalism, an economic system devoted to producing goods for sale on the market in which the objective of the producers is to make a profit, and as much profit as they can. But we still need to ask why capitalism developed when it did? Why only after about 1500? Why not earlier? The answer begins with the recognition that merchants and commerce occupied a low status in the agrarian societies that dominated world history for thousands of years. As we have seen, in these societies landlords controlled the economy and made their living primarily by using peasants to create wealth for them. Landlords have almost always disdained merchants, whom they have regarded as dirtying their hands in the search for “filthy lucre.” But landlords also needed merchants to provide many of the luxury goods they wanted. And so merchants were controlled but could not be eliminated. This gave merchants an opportunity to improve their lot, if only slowly and ...