![]()

Chapter 1

Investigative Psychology:

David Canter’s Approach to Studying Criminals and Criminal Action

Donna Youngs

It is not possible to capture anything more than a flavour of Professor Canter’s contributions thus far to 20th and 21st century social scientific activity in a single volume. In part this is because he is a prolific scientist, exploring everything from alternative medicine (Canter, 1995) to open plan offices, with consultancy work on biscuit and chocolate usage, and the impact of solitary confinement along the way.

The focus in this chapter is on his work in relation to crime and criminals which has dominated his activities for the last quarter of a century. It is no exaggeration to say that he masterminded and actualised the development of a whole new sub-discipline within psychology in a few short years. Working with a team of energetic PhD students, he carried out most of the studies that laid the basis of the new sub-discipline of Investigative Psychology. This early work inspired a first generation of Investigative Psychologists many of whom are now established figures themselves and have contributed to this book.

Others have taken his ideas into a practical context and as a result of what they learnt under his tutelage are now changing the way investigation systems work around the world. Professor Canter himself eschewed the lure of becoming the police’s expert ‘profiler’, preferring instead to limit his forays into working with the police or lawyers to those cases where the science was being used in new and innovative ways. This has given rise, for example, to ways of assessing the possibility of entrapment by undercover officers both in cases of supplying drugs and those pertaining to anti-terrorist legislation. Another instance is his work exploring the veracity of rape allegations.

Perhaps one of his most significant contributions to actual cases in court grew out of his concern at the hold that the Cusum technique was starting to have in legal proceedings, purporting to be able to determine whether the claimed authorship of questioned documents or statements was trustworthy. Notably, he set about carrying out careful studies of the proposed Cusum procedure (Canter, 1992) and even managed to get the Crown Prosecution Service to fund a detailed report that resulted in Cusum no longer being allowed as evidence.

His fascination with the role of psychological analysis of linguistic claims, like Cusum, which have legal implications, that he has called Forensic Psycholinguistics (Canter, 2000), reached widespread public notice in his examination of the conviction of Eddie Gilfoyle for the murder of his wife Paula, even though a suicide note clearly written by Paula was found at the time of her death. Once again, his initial interest in the psycholinguistic challenge of determining the validity of the suicide note, which friends of Paula had claimed was dictated by Eddie, led Professor Canter to set up studies of suicide and associated notes which gave rise to a number of postgraduate dissertations and pieces he wrote directly for The Times (<http://hopc.bps.org.uk/hopc/hopc_home.cfm>; see Canter, 2005).

But the challenge in capturing Professor Canter’s contributions to date is also a product of their eclectic nature and his refusal to follow the perhaps easier, more narrowly-defined route to personal success that is the tradition within academia. Many of those who know him in the investigative context are familiar with his related contributions to the understanding of human behaviour in emergencies from the Bradford City Football Ground fire that gave rise to his contribution to the Popplewell Enquiry and his subsequent book Football in its Place (Canter et al., 1989). He also contributed to the Taylor Enquiry that followed the King’s Cross underground fire (Donald and Canter, 1990). More recently he has studied the evacuation of the World Trade Centre on 9/11. But they are surprised to hear that Investigative Psychology is not the first sub-discipline he has been centrally responsible for creating. Professor Canter’s first specialisation in what became known as Environmental Psychology was originally known as Architectural Psychology. Indeed in his early 20’s when he was a PhD student in the School of Architecture at Strathclyde University (studying the psychological effects of open plan offices, Canter 1968) he organised the first ever Architectural Psychology conference to be held outside the US (Canter, 1970). This involvement in the exploration of human activity in naturally occurring settings was very influential in leading him into his subsequent study of behaviour in emergencies, which was the launch pad for contributing to police investigations out of which Investigative Psychology grew. (He describes this in Mapping Murder (Canter, 2003), as well as in his bestselling Criminal Shadows (Canter, 1994). This intellectual pathway is also documented in Canter (1996) and at <http://hopc.bps.org.uk/hopc/hopc_home.cfm>.

Professor Canter’s Investigative Psychology

From his early work contributing to police investigations and his awareness of how scientific disciplines develop through his experience of the growth of Environmental Psychology, Canter identified Investigative Psychology as a scientific discipline waiting to happen. He saw the need to bring together the contributions that psychology can make to the investigation of all forms of criminal behaviour through the psychological and social scientific analysis of the actions of offenders as well as the investigative strategies and legal processes (for overviews, see Canter, 1993; Canter and Youngs, 2009; and Canter, 2011). From the start he was clear that this encompasses the modelling of patterns of criminal action to facilitate the identification and location of a potential perpetrator through to examinations of detective decision making and interview strategies in an investigation and on to assessments of the credibility and validity of evidence as well as the effective court presentation of the case. It also quickly became apparent that many aspects of legal and investigative processes in civil as well as criminal courts, such as psychological autopsies (Canter, 2000), hostage negotiation and the examination of criminal networks or the forensic psycholinguistics of anonymous letters, were all very appropriately within the Investigative Psychology domain.

Given its power and breadth it is perhaps not surprising, then, that Investigative Psychology represents an increasingly prominent perspective among criminal psychologists. It has reset the focus of forensic psychology over the last two decades, perhaps prompting the Telegraph’s description of Professor Canter as ‘the father of forensic psychology in the UK’. But it is particularly noteworthy that despite its origins deep within scientific, academic activity, Investigative Psychology has also had a significant impact on investigative practice throughout the world, underpinning the development of ‘offender profiling’ and ‘geographical offender profiling’, for example. Specialist IP units now exist in countries including Japan, Israel and South Africa. In the US recognition of his contribution to Geographical Offender Profiling has led to national debate about the most effective of these techniques (National Institute Justice: Evaluation Geographic Profiling Debate; 8th International Crime Mapping Research Conference September 2005, Savannah, USA)

But perhaps the broadest legacy of the rapid emergence of Canter’s Investigative Psychology will come from his mapping out of an approach to psychological research, through the development of this discipline, which has relevance far beyond the criminal context. This is an approach to studying people and their actions in their natural context. In conversation Professor Canter has often referred to this approach as a form of anthropology or even archaeology. By this he means it is a psychological study that looks at what actually happens rather than creating artificial, laboratory situations in which to study behaviour. This is not to confuse his work with the anthropological and archaeological study of cultures past and present. His work is still firmly rooted in the study of individuals. He is also quite comfortable with standard psychological procedures such as questionnaires, provided they deal directly with aspects of people’s actual lives, although he has favoured work that examines their actions rather than what they say about them. Further he has always claimed that it is most appropriate for psychologists to attempt to answer questions initially formulated by people who must act on the answers. This eschews issues that are only of interest to other academic psychologists, but does not prevent him from encouraging exploration of fundamental psychological issues that may be relevant to assisting practitioners and policy makers.

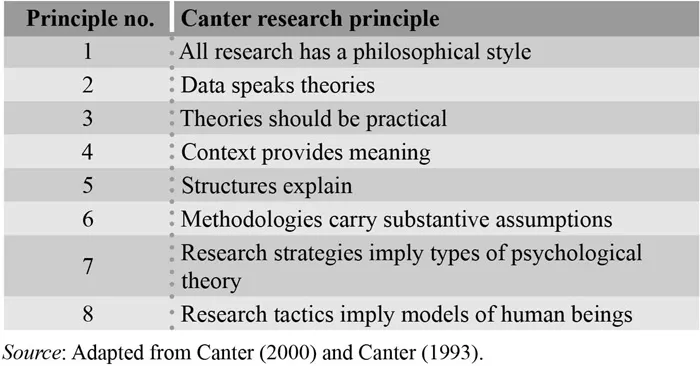

However, he has long emphasised that there is a world of difference between applicable research, applied research and consultancy. Canter sees the need to formulate research questions, methods and results that enables the work to be drawn on by practitioners. Yet he distinguishes this scientific activity from what he calls ‘engineering’, which is the attempt to build processes and conclusions that can be put directly into use. The overall principles (see Table 1.1) on which the approach is based are described in Canter (1993), Canter (2000) and Canter and Youngs (2009).

It is an approach that seeks to work directly with the material available within any context no matter how limited or challenging that ‘data’ may be. But although problem-focused it is an approach that looks for solutions in the understanding of human meaning and agency. This comes together in the approaches Canter developed to allow the advanced and complex quantitative modelling of psychologically-rich qualitative material, producing models that give rise to problem-solving tools and solutions. It is illustrated well, for instance, in his development of methods for linking crimes that draws on advanced conceptual models generated by a form of non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (see Canter and Youngs, 2009).

Investigative Psychology, both as the specific crime and investigation-focused discipline and as a style of and approach to doing psychological and social research, emerged as a result of the tension created by Canter’s attempts to resolve the inherent contradictions in the particular intellectual tendencies and convictions he held. David Canter spent the first six years of his early career within a School of Architecture, where the humanist, artistic academic tradition merges with the concrete, mechanical disciplines. Within this context he developed a keen sense of the different contributions of the different forms of academic discipline to the human condition. As he describes it he saw the engineering and technology disciplines that make life comfortable and the arts and humanities that make it worthwhile. His quest to integrate these fundamentally distinct ways of thinking about human beings is an influence that can be seen throughout his work.

Table 1.1 Canter’s principles for research

David Canter is on the one hand, a conventional empirical scientist yet at the same time, paradoxically, has a strong interest in those aspects of psychology and in particular the significance of human agency that has its origins in the work of William James and George Kelly. He has always argued that, what was known in the 1960’s as the ‘third stream’of psychology – distinguished from the first stream of psychoanalysis and behaviourist second – a constructivist, humanist approach to looking at human beings, but using what many would regard as highly positivist, empirical procedures, was particularly appropriate for a problem-solving psychology that was firmly rooted in what he refers to as ‘real world issues’. Three intellectual strands can be identified, then, within the work of this distinctive psychologist.

‘Third Stream’ Perspective on Human Beings

Professor Canter’s core sympathies sit with the humanist and phenomenological schools. His researches draw on ways of understanding the individual that go back to William James, being concerned with the person’s way of making sense of and dealing with the world. In line with Harre (1979) amongst many others, they assign the individual the role of expert on his or her own life. This standpoint was clear in his earliest student project, a study of his correspondence with his friend, film director Mike Leigh.

This concern with understanding the meanings events and objects have for people as the basis for understanding their behaviour is writ large in his long-standing interest in George Kelly’s Personal Construct Theory. He has used this approach most recently and particularly notably in studies of the radicalisation processes of terrorists; although he first started using this procedure in the school of Architecture in the mid-60s. The studies of terrorists that he supervised (for example, Sarangi, Canter, and Youngs (in press)) were some of the first to examine directly the actual psychological processes of convicted terrorists. In the most recent example of this fascinating work, conducted with a senior police officer (Canter, Sarangi, and Youngs, 2012) Personal Constructs concerning the significant figures in their lives were elicited from 49 Islamic Jihadis in India.

These Personal Construct analyses throw light on the psychological processes of radicalisation of Islamic terrorists and the different pathways to terrorist involvement. To take just one example as an illustration, one terrorist saw himself as very law abiding at the time he met active terrorist X who he saw as a law breaker but he also saw the Police as law breakers. Curiously, the important people in his life include his wife and both Rajeev and Indira Ghandi. Furthermore analysis of this man’s Repertory Grid also shows that this individual does not see any changes in his view of himself in relation to his involvement in terrorism. He was actually convicted of helping finance terrorism and declares that he has no commitment to an armed struggle. This challenges the common belief that Jihadi terrorists are simply driven by fundamentalist religious beliefs. It also shows how Canter sees psychological explanations as part of a broader social set of explanations which he brought together in his recent book on the Faces of Terrorism (Canter, 2009).

Some may be surprised to learn that a third stream perspective also runs through his Geographical profiling work. For although that is concerned with analysing offender spatial behaviour, it is through understanding the sense individuals make of their environments rather than the more mechanistic, direct route learning models that other researchers have implicitly favoured that he has developed his approach. This distinction between a general understanding of the environment and an unthinking use of it he recognised as reflecting the Hull-Tolman debate within 20th century psychology (see Canter and Youngs, 2007). Canter tied offender spatial behaviour into environmental psychological concepts from those outlined in his ‘Theory of Place’ (Canter, 1977) as well as ideas about mental maps, environmental buffers, scale consistency, domocentricity and magnitude estimation (Canter and Larkin, 1993; Canter and Gregory, 1994; Canter and Hodge, 1998; Canter and Hammond, 2006). The much-cited Commuter–Marauder model however was always a heuristic device rather than a psychological theory of offender spatial behaviour. His most recent thinking on the processes underpinning offenders’ spatial decisions, described in the popular book Mapping Murder as well as the Investigative Psychology text (Canter and Youngs, 2009) is opening up considerations of individual differences in this field.

A Problem-solving Focus

Professor Canter’s research has been driven by a basic desire to do something useful. The origins of this no doubt lie in his socialist perspective on the world; the belief that everybody’s challenges have merit and that the focus should be not on any value judgements but on overcoming those challenges. Canter wants to move away from what he saw as the default academic position whereby problems are defined in terms relevant to moving on a given discipline, meaning that academics end up talking only to each other. He sees such a focus as particularly inappropriate for a psychologist because psychology is fundamentally about how people deal with their world and interact with others. Moreover because human beings are enormously adaptable and responsive to their external environments any research that ignores the context of human activity is doomed to be superficial. Consequently, he remains deeply sceptical of the controlled laboratory experiment, with its reductionist, atomising of dependent and independent variables. He sees that methodological emphasis as destroying the possibility of considering the whole person.

Rather than attempting to control out the real world, Canter’s argument is that research should find ways of exploring what people actually do and the processes that underlie those actions. This also allows research to be sufficiently grounded in the concerns of the real world and its results can be integrated directly with action strategies. In this way research is ‘investigative’ ...