![]()

1 Introduction

As I begin writing this book the recent ratification of the ISO 9000:2015 and ISO 14001:2015 versions of the standard come sharply into view, in particular the emphasis on the role of quality, safety and environmental management systems on achieving sustainable development goals. There is a sense that quality management theory has evolved whilst sustainability is evolving (Figure 1.1). The complex nature of sustainability as concept at times leads to an ambiguity reflective of earlier challenges faced by business in regards to Total Quality Management (TQM) (James 2015; Fust and Walker 2007). TQM is a mature management concept defined as an organisation-wide approach to understanding precisely what customers need and consistently delivering accurate solutions “within budget, on time” and with the “minimum loss to society” (James 2015. The concept of customer in this sense includes both “individuals or organisations that are downstream in the life cycle process of a product” and by extension global society (Garvare and Johansson 2010). The development of service–quality improvement processes to create a sustainable environment is compatible with TQM is described as total responsibility management (TRM). As with quality, there is no singular definition of sustainability, but an understanding of quality management helps improve the success of sustainability initiatives (Fust and Walker 2007). There have been suggestions of a conceptual shift in terminology from quality and corporate social responsibility (CSR) to corporate sustainability and responsibility (Figure 1.1).

This may ignite a new quality revolution that builds on concepts such as “doing things right the first time, doing the right things, continuous improvement and innovation” (Zwetsloot 2003). Sustainability/CSR implementation shifts the focus beyond mechanistic systems to value-driven decision making for both the organisation and society – “doing the right things” (Zwetsloot 2003). This avoids misalignment of organisational goals and stakeholder interests and prevents the aggregation of risks created from “known knowns”: “there are things we know we know or known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know but there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know” (BBC 2007). Deforestation, resource scarcity and lack of biodiversity are “known knowns,” and continuing apathy for these risks manifests itself in their acceptance as the price of human progress. Climate change, the ultimate risk multiplier, fits all three categories (“known knowns”, “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns”) with acceptance on an individual level of the phenomena of increasing greenhouse gas (GHG) levels in the earth’s atmosphere but limited appreciation of the effects on natural cycles (e.g. weather patterns) (James 2015). The goal of sustainable development aims to meet “the needs of the present without compromising the future”, which in itself presents uncertainty as the future is unknown. What is known is that the earth is finite, with interconnected natural cycles. This understanding supports the use of the “one-planet living” approach, engendered to resolving rather than balancing the pillars of sustainable development (society, environment, economy and information) or the three Ps of sustainability (people, planet, profit); the ubiquitous manifestations of twenty-first century progress (waste electrical and electronic equipment, or WEEE); and the looming presence of artificial intelligence and robotics (Tsai and Chou 2009; Environmentalist 2015a; James 2015). Alternatively, should global society focus on the sustainability issues of the “few” 100 companies that account for 71% of global GHG emissions whilst discounting the wider economic actions and consumption choices of the “many” (CDP 2017). To overcome the socio-economic and operational complexity created by climate change and environmental degradation, leaders require evolved sustainability thinking and adoption of multi-criteria decision aids (Porter and Derry 2012).

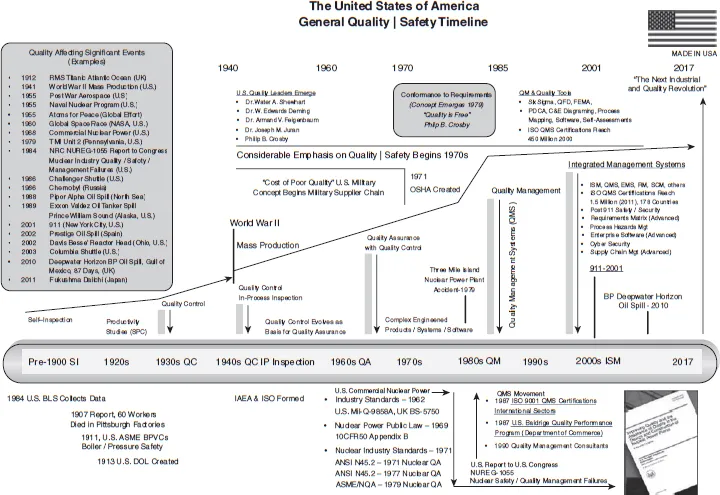

Figure 1.1 General quality and safety timeline (GQM Advisors 2017)

Businesses that were early adopters in the TQM revolution during the twentieth century (e.g. Toyota and Motorola) are paralleled today by organisations that view sustainability as a profit centre rather than a cost centre (Fust and Walker 2007; James 2015) (Figure 1.1). TQM in its post industrial revolution reincarnation has focused on three main themes: variation reduction, waste reduction and loss. Early emphasis on these themes, evident in Henry Ford’s assembly line, was an attempt to instil craftsmanship and reduce variation in automobile manufacture – but Ford found scrap wood and metal to be an undesirable output. With his leadership at Ford Motor Company, alternative uses for scrap wood were found in energy generation and the development of charcoal briquettes, which are still used in outdoor barbecues (Ford 2015). Similarly early adopters of sustainability/CSR initiatives reap competitive advantages arising from improved organisational structures, and better talent management and risk management (Fust and Walker 2007). Quality management is mirrored through three evolutionary stages:

- Early – sustainability change initiatives are adopted as part of risk reduction.

- Intermediate – sustainability change initiatives viewed as both a risk and opportunity.

- Advanced – sustainability change initiatives considered a competitive differentiator.

(Fust and Walker 2007)

Therefore sustainability and quality are arguably both sides of the same coin, with sustainability propelling the need for TQM (Zairi 2002). “Without sustainability there is little benefit to be gained by TQM” (Curry and Kadasah 2002). Similarly, without TQM, sustainability as a concept has limited applicability in a rapidly evolving socio-economic landscape. Interconnectedness has become acute in an era of human labour displacement with preference for automated or robotic systems as both organisations and individuals are striving for telos or purpose for their existence (James 2015). This reveals itself in the business context in terms of values, mission statements and policy (James 2015). The tragedy for organisations such as Volkswagen is that although it does not belong to a “sin sector” (e.g. alcohol, tobacco, gambling, nuclear energy and firearms industries), its foundations are based on a nefarious purpose that cannot be divorced from its present context (Grougiou et al. 2016). Unethical actions by the organisation affected Volkswagen’s license to exist, license to operate and license to sell its products/service globally (Labuschagne and Brent 2005).

Volkswagen was established by the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF), or “German Labour Front”, of the Nazi Party as part of its Kraft durch Freude, or “Strength Through Joy” program, as free trade unions were banned under Hitler’s leadership (BBC 2015). The Strength Through Joy program was meant to appease workers by providing subsidised cruises and holidays, an affordable automobile, and social activities once the domain of the German upper classes. This program was implemented along with Schönheit der Arbeit, or “Beauty of Work”, the improvement of factories and work spaces, the emphasis being “smoke free” environments. The Volkswagen, or “peoples car”, and its iconic “beetle” design was produced in 1938 with the intention to provide German workers with an automobile at the price of a German motorcycle, through a payment plan. Many German workers opted for this payment approach, but with the onset of war some prospective car owners lost their deposits (Auto News 2015). This led to protests regarding the leadership of the DAF under Dr Robert Ley, who boasted that he controlled workers’ lives from the cradle to the grave (BBC 2015a). Subsequent Volkswagen automobiles for both domestic and military use prior to 1945 were made by an estimated 15,000 slave labour victims from concentration camps who comprised 80% of the company’s wartime workforce (NY Times 1998). In 1998 Volkswagen accepted corporate responsibility for its actions and set up a fund to compensate victims.

The use of forced labour is not relegated to black and white newsreels from a darkened past. The International Labour Organisation estimates that there are 20 million people in forced labour worldwide, 90% of them in the private sector – more than the estimated 12.5 million Africans shipped to the Americas during the transatlantic slave trade, which created the foundations of our global trade system (Environmentalist 2016c; PBS 2017).

In its post war reincarnation Volkswagen develop a renewed purpose as Das Auto, or “the car”, built around a fun, friendly image of the “beetle” shape embellished with pictures of flowers and bright colours, as popularised in Disney movies such as Herbie Goes Bananas – a long way from the militarised look of the original models. The whimsical nature of the Herbie film genre had a lasting impression on my childhood, as one of my elementary school teachers owned a Volkswagen that some of my classmates described as a “dustbin on wheels”. This analogy was not unfounded when compared with Japanese brands such as Datsun, which not only provided economy but were quieter due to the use of coolant rather than air to reduce the engine temperature (BBC 2015a). The company continued its focus on volume rather than quality as its strategy for success. Consecutive Volkswagen executives pursued this expansion strategy, acquiring 18% market share in China and 22% in the Brazilian market, coupled with a ruthless search for cost savings through component sharing between production models (Economist 2012). The effects of this strategy are evident in Volkswagen’s wind noise issue in 2011 and prior power train non-conformity, contributing to a decade-old crisis in reliability that has not been forgotten by consumers in key markets such as the United States (US), where sales fell by 22% in summer 2014 (Business Insider 2014). The J.D. Power Initial Quality Study has consistently rated the Volkswagen brand near the bottom for every year except 2009 (Business Insider 2014).

The engineered rigging of emissions test and data arguably is symptomatic of an organisational culture with a misaligned purpose on “the car” rather than the customer/stakeholder, i.e. global society. As a result, more than 1M tons of pollution have been produced in the form of emissions to air (e.g. nitrogen dioxide, or NO2) from approximately 11 million vehicles containing rigged components (Guardian 2015). Pollutants such as nitrogen oxide (NO) and NO2 pose a respiratory threat to humans and animals by inflaming breathing passages. The European Union is disproportionately at risk due to the higher level of diesel vehicle ownership when compared to the US where 3% of automobiles use diesel (Guardian 2015).

The Volkswagen quality ethos is focused on reliability, visual appeal and service with the absence of sustainability. Sustainability can be achieved by cultural acceptance within the organisation that it has a duty to global society arising from the life cycle impacts of its products and services – its corporate sustainability footprint. Sustainability footprints are methodologies for assessing the social and environmental impacts of the economic investment in a specific strategic option in relation to other strategic alternatives, and their potential risk to the survival of future generations (e.g. carbon footprint); these methodologies can assist Volkswagen in monitoring and measuring its business performance, leading to a culture of innovation instead of deception (James 2015). By implementing sustainable business practices, Volkswagen will transform from being Das Auto to rather truly being the “people’s car”, thus putting individuals and society at the core of its corporate strategy and adopting a cradle-to-cradle approach to managing its processes. The Volkswagen emissions scandal is symptomatic of a far wider erosion of trust between business and society that pre-existed the financial crisis of 2008 (Zink 2005; Castka and Balzarova 2007). This lack of trust between business and society is a failure of CSR, corporate citizenship and sustainability initiatives in delivering:

- reduction of climate change impacts despite environmental best practices and increasing environmental degradation with 21% of plant species facing extinction affected by a changing climate (Environmentalist 2016f);

- green washing effect of CSR reporting that masks the impact of corporate activities being “less bad rather than good”; and

- good corporate governance that would not naturally accrue within a market-driven economic context (Visser 2010).

CSR is also hampered from having a revolutionary impact organisational performance in three main areas.

1.1 Incremental CSR

The implementation of CSR initiatives emphasises incremental improvements to address the challenges of sustainability and environmental and social governance (ESG) concerns, being underpinned by concepts that evolved within the quality management movement concerning continual improvement (Visser 2011). The ISO 14001:2015 standard takes into consideration continual improvement as an underlying principle that supports organisations seeking a fine balance between sustainability and profit making (Visser 2011).

1.2 Peripheral CSR

Social responsibility activities are an extension of public relations campaigns, an absurdity that persists in the presence of initiatives to create infrastructure, and to appoint a CSR manager and other personnel in support the achievement of organisational objectives (Visser 2011).

1.3 Uneconomical CSR

Sustainability and CSR initiatives do not necessarily translate themselves into shortened lead times between investment and rewards, which may be non-financial in nature (Visser 2011).

To bridge the gap between stakeholder perceptions and actual outcomes there should be synergy between CSR, corporate governance and quality (Castka and Balzarova 2007). Fortunately some leaders have “awoke to the reality”, taking steps to refocus organisational efforts on quality by constituting expert panels to examine quality, environmental and safety issues (James 2012) In a nutshell, decisions are being made close to the source with project schedules and costs not given priority over quality. Therefore the risks (i.e. the likelihood or consequence of sustainability impacts) that are unaccounted or unconsciously acceptable to senior management are reduced.

However as identified during the early period of the quality management revolution, some stakeholders consider sustainability/CSR as an “unrecoverable cost” that is incurred based on a weak business case (Castka and Balzarova 2007). As with quality, sustainability/CSR concepts fall on barren ground, with limited interest in developing a sustainable business culture, resulting in the development of an aspect-based approach where quality is the domain of the “quality department” (Metaxas and Koulouriotis 2014). Within this backdrop it can be surmised that sustainability is the new quality. There is undoubtedly is synergy between sustainability/CSR and quality. The quality movement can be invigorated if it embraces sustainability as a concept; alternatively it can stifle sustainable innovation despite the benefits of embracing standardised approaches embodied in the ISO 26000 or by building on the implementation of existing standards (Guardian 2011). The embodiment of management technology approaches such as the ISO 9000:2015 and ...