![]() PART I

PART I

The European Perspective![]()

CHAPTER 1

What is “Ethnic”? Reappraising Ethnic Food and Multiculturalism among the White British

SEAN BEER*

Keywords

gastronomy, ethnic, ethnic food, Great Britain.

Abstract

This chapter explores some of the issues related to the nature of the terms “ethnic” and “ethnic food” within a multicultural Great Britain. The analysis focuses on definitions of ethnicity and whether white British ethnic groups exist with distinctive language, art, culture and gastronomy. Evidence in support of this distinction comes from an examination of popular interest in white British food and a regional case study of West Country cooking. The term “ethnic” is a complex one, but, the author concludes, must be used inclusively or possibly be eliminated altogether.

Introduction

The word “ethnic” seems to have varying applications. By its very nature, the term is a social construct that has been developed from an epistemological perspective, though based on ontological truth in terms of varying ethnicity. As such, it is used by many people in different ways, although in Great Britain, it is largely used in association with comparatively recently migrated, predominately non-white racial groups. The contributions of these groups to a dynamic food culture and the culture of the country cannot be underestimated, but what of white British ethnic groups and their food culture? Do such groups exist? Are there distinctive gastronomies, and can the term “ethnic” be applied to these groupings, or are there different and more appropriate approaches?

This chapter explores some of the issues related to the nature of the terms “ethnic” and “ethnic food” within a multicultural Great Britain. It starts by considering definitions of ethnicity and how it is determined according to government classifications; definitions based on customs, language, dialect, food and geography; and the idea of self-determination. The discussion then moves to an examination of whether white British ethnic groups exist. The analysis focuses on ideas of localness, rurality, language, art, culture and gastronomy, which provide evidence in support of the concept of distinctive white British ethnic groups and gastronomies. An examination of popular interest in white British food and a regional case study of West Country cooking further supports this notion. The chapter concludes with concerns about the loss of heritage and authenticity and the nature of the term ethnic. The term is complex and must be used inclusively. If it continues to be used as it currently is, particularly in a pejorative way, it debases the culture of non-white British ethnic groups. If the term is used in a more positive way but to the exclusion of white British ethnic groups, it in effect denies the ethnic origin of white British and their cultural heritage. Possibly, it is best to stop using the term altogether.

Definitions

As a term, “ethnic” has been used in a variety of different ways. Generally, though, reference to the term in a British context describes groups of people connected by race, although the use of this term remains complex. When “ethnic” groups are referred to within the population, they tend to be minorities that have formed part of society comparatively recently. Thus, among many others, Great Britain contains Afro-Caribbean, Chinese, Indian and Pakistani ethnic groups that form parts of a modern multicultural society.

British society has always been in flux, having experienced past, often violent, migrations of Anglos, Danes, Romans and Normans. Thus, it is difficult to refer to a settled or homogenous cultural map at any one time. Further complications result because of the connection between the term “minority” and ethnic, which indicates that a particular group forms a minority of the total population. Yet, geographically, concentrations of particular groups might not represent a minority within a particular subregion or area, even if they do on a national basis.

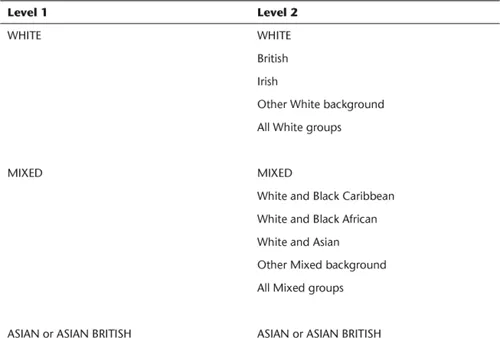

These classifications have been formalized in several ways. Perhaps the most accepted is the National Statistics classification (identical to that used in the 2001 Census in England and Wales), which contains the groups indicated in Table 1.1.1

The general tendency has been to ascribe the term “ethnic” to more recently arrived groups in society. In Great Britain, these groups tend to be non-white, though there also are recent developments with regard to white European groups, such as Polish and Latvian migrants, as well as more established groups, such as Italians and Greeks. However, the term “ethnic” does not seem to be applied to subgroups of white British people, which in many ways represents an anomaly. When we look at ethnicity from a cultural or sociological perspective, a more reflective definition indicates that we refer to a group of people whose members identify with one another on the basis of a presumed common genealogy or ancestry.2 Other common traits may include culture, language, geography or even recognition by others. This term therefore may be contrasted with race, which tends to indicate common physical and genetic traits.

Table 1.1 Ethnic classifications used by the Office of National Statistics

Race and ethnicity can be sensitive areas for discussion. In this context, the use of the term “ethnic” in relation to food is an interesting and complicated issue. For example, do people from non-white ethnic groups feel offended by having their gastronomy and themselves labelled as “ethnic” and do white people feel left out? Is “ethnic” the best term to use?

Are There White British Ethnic Groups?

So what of the ethnic white British and their subgroups? Do they exist? What of the lost tribes of the white British? Do they have distinctive gastronomies and gastronomic histories? Why do we not recognize them and celebrate them as we do other ethnic cuisines? It might be argued that the white population has become homogenized and that, as a result of migration, immigration and intermingling, ethnic diversity has declined. But is this really the case? Certainly there is evidence to suggest diversity in the white population. Customs, language, dialect and food all indicate potentially different ethnic groupings, often (though not necessarily) on a geographic basis, and differentiation on a geographical basis is one of Smith’s criteria for ethnic identification.3 Thus, Welsh, Scottish and English groups exist; the English category contains the Cornish, Cumbrians and Devonians.

At this juncture, two crucial points are necessary. The phrase “white British” does not exclude people of non-white backgrounds who belong to those groups. Rather, it is a term that recognizes antecedence, whether by blood or adoption, and the right of individuals to decide on their own ethnic background, just as individuals in Great Britain have the right to decide their own gender. As such, “white British” may be considered a clumsy term, but it is probably the best that we have. Second, for many white people, the act of trying to identify and tie down their ethnicity creates dissonance. It forces them to look at the past, consider injustices that may or may not have been committed by one ethnic group on another, and question motives. Billy Bragg, long the singing standard-bearer of the Left in Great Britain and a fervent campaigner against racism, has addressed these very issues in his book The Progressive Patriot.4 His important, somewhat controversial stance explores the nature of what it means to be a white English man, a discussion that the Left is often uncomfortable with and that the Right seems, at times, fixated on. The Progressive Patriot offers an excellent account of Bragg’s attempts to reconcile the many things that constitute his Englishness and, in many ways, review his own ethnicity. The account has been a long time coming; its roots can be seen, as he admits, in his most political album, The Internationale, as well as his 2002 album England, Half English. Further discussion in this chapter should be taken in this light. In the spirit of acknowledging the subjectivity of qualitative research, I also acknowledge that I have faced turmoil similar to that Bragg describes in looking at his past, which may emerge in the following analysis.

LOCALNESS

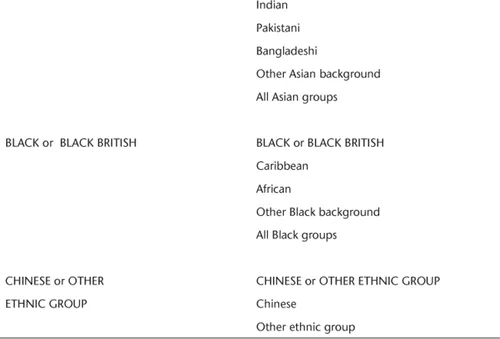

During the past decade, growing interest in food and where it comes from may have derived from insecurities about food as a result of problems such as E. coli infection, BSE (bovine spongiform encephalopathy), and foot and mouth disease. Changes in attitudes towards animal welfare, support for the natural environment and support for local economies and the British farming industry may also have had an effect. Food consumers are gradually experiencing more complex motivations and, theoretically, becoming more demanding in many ways, both collectively and as individuals. Yet it remains debatable whether this complexity really exists or whether there are considerable divergences within the population. In other words, consumers may look at food from a whole host of different perspectives,5 as indicated in Figure 1.1.

In turn, it becomes valuable to consider in more detail the idea of localness. Considerable evidence suggests that localness has become very important for some consumers.6 In this context, local may be a euphemism for ethnic white, but, then again, not all local food is of white British origin, although much is. All ethnic white food may be local (presuming that is it is being sold locally), but not all local food is ethnic white – just as a square is a rectangle but a rectangle is not a square.

Figure 1.1 An impression of the range of perspectives with which British consumers may well view their food choices

Source: S. Beer (2008).

Organizations that try to promote and protect local distinctiveness include the Campaign for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE),7 which has been involved in this sort of campaigning since 1926. A registered charity, with 60 000 members, the organization actively tries to support local food production and consumption. Various publications, including Sustainable Local Foods,8 Local Action for Local Foods,9 Mapping Local Food Webs10 and The Real Choice: How Local Food has Survived the Supermarket Onslaught,11 along with active campaigning, have aimed to support local food production and consumption. The organization Common Ground12 has also worked hard to promote all aspects of localness. Its rules for local distinctiveness highlight the direction from which they, and a number of other organizations, are travelling. Som...