eBook - ePub

Blaming the Government: Citizens and the Economy in Five European Democracies

Citizens and the Economy in Five European Democracies

This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Blaming the Government: Citizens and the Economy in Five European Democracies

Citizens and the Economy in Five European Democracies

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This work examines the impact of macroeconomic conditions on public support for the government in Britain, France, Netherlands, Denmark and Germany.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Blaming the Government: Citizens and the Economy in Five European Democracies by Christopher A. Anzalone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

Introduction: Politics, Economics, and Public Opinion

All political history shows that the standing of a

Government and its ability to hold the confidence of the

electorate at a General Election depend on the success of

its economic policy.

Government and its ability to hold the confidence of the

electorate at a General Election depend on the success of

its economic policy.

—Harold Wilson, cited in

Watt, “Labour’s Hard Road to Recovery,” 1968

Watt, “Labour’s Hard Road to Recovery,” 1968

Without the benefit of an election, in October 1982 the German Free Democratic Party (FDP) left the government of Social Democratic chancellor Helmut Schmidt. This marked a watershed in post-war German* politics as Schmidt’s party, the Social Democrats (SPD), had governed with the FDP in a coalition for thirteen years, since 1969. What drove the change? The answer lies, at least partly, in the dynamics of public support.

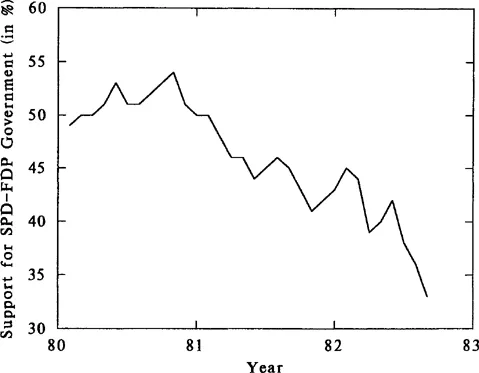

Figure 1.1 shows popular support for the incumbent SPD–FDP coalition between 1980 and the end of 1982. The graph reveals how public support for the governing parties, expressed in monthly polling data, steadily deteriorated after the 1980 election until the FDP left the government. Apparently, the FDP leadership believed that such a massive erosion of public support indicated the public’s desire for a change of government and threatened the party’s chances of survival after the next election, given the 5 percent threshold built into Germany’s system of proportional representation (Dalton 1993).

Figure 1.1. Support for the German SPD-FDP Coalition Government, 1980–1982

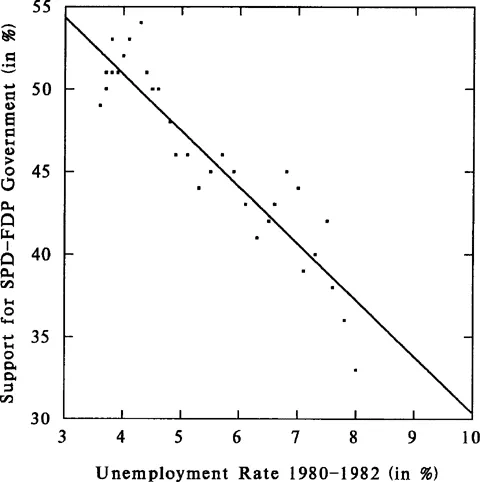

What may explain the sudden and extraordinary downturn in public support for the governing coalition? Figure 1.2 plots the popularity of the German government between 1980 and the end of 1982 and the monthly rate of unemployment. As unemployment rose after the 1980 election, the fortunes of the SPD–FDP government under Chancellor Schmidt plummeted. The graph thus seems to suggest that at least part of the explanation for the decline in public support for the government has to do with hard economic times. Both the break-up of the governing coalition and the government’s standing with the public appear to have been influenced by two factors: public opinion and economic performance.

This book tells a story about the connection among politics, economics, and public opinion. Conventional wisdom has it that the state of the economy drives public support for governments. Yet the relationship between economic performance and mass opinion appears to vary in strength and direction across time and across countries. Why? In order to answer this question, I examine the impact of macroeconomic conditions on government support in five West European countries between 1960 and 1990. It is my thesis that theories that seek to relate economic conditions to public opinion require the systematic incorporation of a country’s politics and institutions—that is, the political context—in explanations of government support.

Figure 1.2. Support for the German SPD-FDP Coalition Government and Rate of Unemployment, 1980–1982

Public Opinion, the Economy, and the Political Context

Public opinion matters. What people think about politics—especially in the aggregate—matters to politicians seeking election or defining policy agendas, to journalists trying to find a new story, and to political scientists who are interested in the connection between citizens and their governments in democratic polities. Representative democracy as a form of government has an inherent need to know what people think about politics, not only on election day, but also during the course of a government’s tenure: public opinion is a constraint on political choices.

Fifty years of systematic research on political attitudes and behavior have taught us that citizens’ abilities to understand politics and the time they spend thinking about politics are limited and in many ways incompatible with the lofty ideals of democratic theory. But we have also learned that voters are not fools (Key 1968), and that, by and large, they have a reasonably good understanding of political life, considering that most people prefer to think about their jobs, their families, their friends, or such seemingly (to political scientists, that is) mundane things as the latest hockey or basketball results. Politicians and political observers take note of what the public thinks about politics when they propose policies or make public statements. In fact, most modern democracies have developed well-functioning survey industries that constantly take the pulse of public opinion by polling representative samples of the population on who is up, who is down, and what the country’s most pressing problems are. Public opinion polls, conducted at regular intervals, are of great help to politicians and policymakers for gauging whether citizens are satisfied with the way the people’s affairs are handled. At the very least, polls provide a quick and rough regularized indicator for the public’s preferences.

The economy matters as well. The politics and economics of democratically governed societies have long been intertwined. It is, for example, widely accepted political lore that democratic governments are more likely to fall when economic performance is less than satisfactory. Virtually all politicians will concede that favorable economic performance is beneficial to incumbents. This implies that the performance of the economy influences what ordinary people think about politics. In particular, it implies that incumbents are held responsible for whether there are jobs and whether people can afford to buy the things they need. In fact, the economy is of such overriding political concern to citizens and politicians alike that virtually all advanced industrialized democracies have developed political institutions that are designed to help governments manage the economy in order to avoid the social and political consequences that can result from inferior economic performance.

We have also long been aware that institutions and political structures matter. They matter because they “provide the framework within which human beings interact …” (North 1981: 201).1 Constitutional rules are the most fundamental constraints on political behavior because they determine the range of political choices for citizens. While public opinion may drive politics to some extent, the structure of political institutions at least partially determines the way people think about politics. Moreover, politics and political contexts vary widely across individual countries. Party systems, political events, and power relationships also differ across countries and are themselves subject to change over time. Given the fact that institutional structures and political contexts vary across democratic systems, what and how people think about politics vary as well.

Public opinion, economics, and political structures play crucial roles in the functioning of democratic societies. What, then, is their interrelationship? This study is an attempt to explain some of the links among these three elements of democratically governed capitalist societies. It is argued in subsequent chapters that public opinion, economics, and a country’s political context (which includes its institutions) are intimately intertwined dynamic phenomena. Both economic performance and political structures—broadly conceived—are variable across time and across countries, and both influence what people think about incumbent governments.

The following questions guide this inquiry: First, is there a relationship between economic performance and public support for the government? Second, is the relationship necessarily negative, that is, do mass publics necessarily blame the government during hard economic times? Third, how can politics and political institutions be systematically incorporated in models of government popularity?

I argue below that the effects of economic performance on the popularity of governments are better understood if a country’s political context and political institutions are systematically incorporated as part of the explanation together with indicators of economic performance. Put simply: if we seek to understand the ups and downs in government popularity, we need to understand both its economic and its political determinants and establish their systematic effects.

Economics and Political Behavior

There are three main elements to the study of politics and economics in advanced industrialized democracies (Hibbs and Fassbender 1981; Clarke et al. 1992): the economy, citizens, and governmental actors. These components constitute what has frequently been called the political-economic system.2 Figure 1.3 shows a simple version of such a system.

The components of the political-economic system are expected to interact in the following way: The electorate expresses support for governing and opposition parties both at election time and in between, based on the performance of the economy. If economic conditions are good, so the most common argument goes, the electorate will reward incumbents, while it will punish the government if economic performance is less than satisfactory. Political actors are usually well aware of their standing with the mass public, as well as the potential political consequences of inadequate economic performance. It has often been alleged that governments therefore attempt to influence economic policy outputs by manipulating the levers of fiscal and monetary policy (for discussion, see, e.g., Alt and Crystal 1983; Clarke et al. 1992). The outcomes of such attempted manipulations—that is, economic conditions—serve as guidelines for the electorate’s evaluations of government performance.

This admittedly simple representation of political-economic interactions has the virtue of describing almost all areas of interest to scholars of the domestic political economy. Each of these elements, their interaction, as well as the entire system, have been the focus of intense scholarly efforts (Hibbs and Fassbender 1981; Alt and Crystal 1983; Clarke et al. 1992). This study is not concerned with the attempted or successful manipulation of economic levers by governments with the aim of achieving desired policy outcomes.3 Instead, it focuses on the connection between the electorate and government support and on the role economic conditions play in shaping that connection. However, it is important to recognize that citizens must assign responsibility for economic performance in order for there to be a relationship between the electorate and gover...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1. Introduction: Politics, Economics, and Public Opinion

- Chapter 2. Post-War Economic Performance and Management in Western Europe: Growth, Decline, and Transition

- Chapter 3. Politics, Citizens, and the Economy in Western Democracies

- Chapter 4. Politics, Institutions, and the Definition of Incumbency

- Chapter 5. Models of Government Support in Western Europe

- Chapter 6. Politics, Economics, and Support for Coalition Governments

- Chapter 7. Popular Support for French Presidents and Prime Ministers: The Consequences of Institutional Uncertainty

- Chapter 8. Politics, Economics, and the Structure of Credit and Blame: An Exploration into Measuring Responsibility

- Chapter 9. Citizens, the Government, and the Economy: Conclusions

- Appendix: A Note on Data Sources

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author