![]()

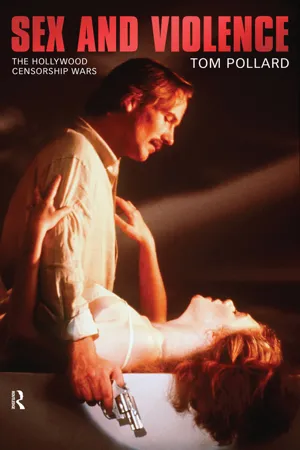

Chapter One

Introduction to Movie Censorship

When audiences sit down in theaters, on airplanes, or in the privacy of their homes and hotel rooms to watch Hollywood films they rarely consider the rules and regulations governing the form, content, and advertising of the motion pictures they view. Most recognize that ratings provide information about the acceptable age of film audiences, although few know the complex assessment structure behind the ratings—currently ranging from G (general audiences, all ages admitted) through NC-17 (no one seventeen and under admitted). Few ponder the tense, behind-the-scenes negotiations between filmmakers and the Classification and Rating Administration (CARA) of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), the outcome of which determines a film’s financial success or failure, or realize the unofficial power of lobbyists, journalists, clergymen, and powerful organizations that pressure studio executives and film raters advocating their own agendas. Even fewer know of the historic struggles involving censorship, sexism, and racism that periodically embroil the film industry.

From the very birth of motion pictures filmmakers faced censorship. They swiftly adapted by inventing ingenious strategies to minimize artistic restrictions. With some modification, this early dynamic between censors, producers, and audiences remains operational today. The level of controversy over film ratings continues unabated, and interactions between producers and regulators can turn contentious at any stage of the rating process. By learning to evade censorship filmmakers crafted some of cinema’s greatest classics and most enduring genres, and their evasion strategies remain vital to the filmmaking process even today.

Conflicts surrounding film ratings reflect broader sociopolitical “culture wars” that continue to flare even today. Current conflicts often pit “conservatives” against “liberals,” terms that defy precise definitions, although conservatives traditionally demand strictly enforced regulations aimed at sanitizing movies from offensive scenes, episodes, images, and dialogue, claiming that a “liberal media” dominates movie content. Liberals grant filmmakers greater latitude to craft their movies. Film critic Michael Medved charges that currently liberal movie critics undermine traditional social values. Medved writes:

Why is the critical fraternity so liberal now? It didn’t used to be. There used to be very conservative critics and they put out reviews from a specifically moralistic point of view. What’s amazing to me was how that entire voice representing that third of America who consider themselves conservative is basically not represented other than by myself in the film commentary business.1

Conservative commentators like Medved often assume a liberally biased media without attempting to prove or justify these views, and the term liberal media has acquired a life of its own. An online journal, NewsBusters: Exposing and Combating Media Bias, recently embarked on a mission to expose “liberal bias” in media without bothering to prove the existence of the alleged bias. Such charges frequently occur, usually without proof or justification.

Noam Chomsky refutes the “liberal bias” claims as a myth, given the enormous cloud of large media corporations headed by conservatives like Rupert Murdoch. Chomsky refuted charges of liberal bias in a 1997 documentary titled The Myth of a Liberal Media. And, despite the frequent cry of liberal bias, the conservative Fox News currently outpolls all other television news programs. Other cable news channels, including CNN, increasingly reflect Fox News’s conservative bias. These corporations also control movie theaters and movie ratings services. In addition, religious movie ratings services currently provide mass audiences with their spin on the latest movies. Established periodicals including The Christian Century, Movieguide, The Conservative Voice, and The American Conservative currently host online movie ratings services. Recently, critic Roger Ebert appealed to both sides of the debate to moderate the level of acrimony in their writings and embrace critical diversity: “I think both the left and the right should celebrate people who have different opinions, and disagree with them, and argue with them, and differ with them, but don’t just try to shut them up.”2 Unfortunately, if the past is any indication, Ebert’s pleas may go unheeded, as political and religious beliefs continue to affect movies as they always have.

Production Codes Defined

Movie ratings derive from Production Codes, systems of rules and regulations governing film form and content. In order to placate detractors, Hollywood periodically reinvents Production Codes, which then play powerful roles in forming film genres, conventions, and social and political messages. Clashing social movements promote competing codes, each reflecting popularly held values and beliefs, which ultimately result in film censorship. For example, during the permissive pre-code period of the late twenties and early thirties weakly enforced rules allowed filmmakers to depict the newly emancipated female “flappers” as well as the bootleggers who supplied them with abundant alcohol. Heroes of this period included seductive vamps and flamboyant gangsters, but by 1934, fueled by a massive religious boycott, a more restrictive code appeared that forbade the popular “gold diggers,” flapperlike female characters who seduce men, as well as bootleggers, rum runners, and other Prohibition-era protagonists. In response, filmmakers created more subtle characters who still managed to evoke the forbidden lifestyles. These struggles over film form and content constitute Hollywood’s “censorship wars” in action.

Critics often employ the term Production Code synonymously with “Hays Code,” which applies to one particular set of industry rules and regulations in effect during 1934–1968. However, Production Codes existed long before the Hays Code, and other codes arose after the Hays Code’s demise. Today, Production Codes continue to exercise considerable influence on film form and content. In this study the term Production Code describes any system—formal or informal—that influences and attempts to regulate motion picture form, content, and advertising. Formal Production Codes date back as early as 1909, and informal ones arose even earlier. Before 1909, court cases, state and local governmental actions, and influential individuals and organizations created informal “codes” by which filmmakers learned the often painful limits of their art. Formal codes appeared in 1922, 1927, 1930, and 1968. The Hays Code (1934–1968) embodied portions of former codes, and today’s MPAA Code retains many of the same basic issues, updated for contemporary tastes. A study of the history of Production Codes and the surrounding controversies exposes aspects of the film industry normally hidden from public view. In fact, wars between producers and censors provide graphic evidence of society’s most taboo issues.

A few codes eventually grew stronger and more effective than others at censoring films. The Hays Code exercised the most influence, but the current MPAA “Valenti Code,” which arose in 1968, remains in many respects equally potent. Whether weak or strong, codes function as effective buffers between the film industry and its more obstreperous critics. The existence of codes presents the appearance of vigorous self-censorship, often staving off more restrictive governmental intervention. There are other unstated rules and regulations, like the potent McCarthy code and the current evangelical code. All of these codes, whether formal or informal, wield a form of control over film form and content, as the following chapters reveal.

Initially, codes arose informally through mutual understandings between producers and outside pressure groups and eventually formalized into written documents and organizations designed to enforce rules. Formal codes censored film content, distribution, and advertising, functioning at times as virtual laws regulating film content, while at other times performing as weak negotiating bodies armed with little real authority. Today most code “enforcement” more closely resembles “negotiation” than adherence to formal laws, a dynamic process of give-and-take between producers and censors.

Hidden Censorship

As Gerald Gardner observes, “not all censorship originated in Hollywood and the state censor boards.” From the beginning, he notes, “pressure groups that represent special interests” constituted “some of the most powerful forces for censorship.”3 Lobbyists, pressure groups, and political and military spokespersons pressure studio executives to suppress various plot elements and controversial subjects. For example, liquor industry lobbyists urge producers to include scenes of alcohol consumption and suppress scenes depicting the harms of alcoholism, while tobacco representatives and soft drink manufacturers persuade producers to focus on the pleasures of their products. The cumulative effect of the presence of lobbyists and pressure groups functions as a hidden “code.” The McCarthy movement and the evangelical movements exemplify this hidden censorship. McCarthyism profoundly influenced film form and content for an entire generation. At the same time filmmakers learned to code their films with symbolic attacks on McCarthyism that often escaped attention. As a result, many McCarthy-era films share a defiant yet symbolic subtext. Today another powerful code demands family-oriented films and strict limits on movie sex. Producers ignore this large group, constituting more than one-third of film audiences, at their peril. Hollywood obligingly produces a growing number of evangelical-oriented family values films designed with this audience in mind, and in so doing practices a kind of self-censorship regarding film form and content.

Movies’ powerful role in youth socialization remains the most often-cited rationale for regulating motion pictures. Even more than novels, motion pictures engender efforts to protect children from exposure to features with “adult” content. Although novels may ridicule or satirize sacrosanct values and beliefs, films pose a far greater threat to the status quo due to their ability to reach mass audiences, causing mounting pressures to reflect conservative social values. Critics often cite the hypnotic attraction of movies to justify censorship and control, assuming that movies function essentially as a form of brainwashing. In fact, motion pictures always fascinate children, who flocked to the earliest nickelodeon features, composing around one-third of early audiences. Today, children, especially teenagers, dominate movie audiences as never before.

Censorship Wars

A fascinating history of controversial social and political beliefs emerges from an examination of Production Codes. At times, conflicts focus intensely on political values and beliefs, while at other times they evoke religious or social issues. The conflicts surrounding film regulation reflect widespread social change, dissension, dissatisfaction, and turmoil. As a part of the larger cultural battles, conflicts over movie ratings punctuate the history of motion pictures, providing valuable insights into social taboos and sensitive issues and ideas. Ultimately, hero types reflect restrictions imposed by Production Codes, as different codes encourage different heroes. As codes change, so do the protagonists and villains. Tami D. Cowden, Caro LaFever, and Sue Vidors postulate the existence of eight “archetypes” for both male and female characters in popular media. Male archetypes include the chief, the bad boy, the best friend, the charmer, the lost soul, the professor, the swashbuckler, and the warrior. Female archetypes include the boss, the seductress, the spunky kid, the free spirit, the waif, the librarian, the crusader, and the nurturer.4 Film ratings conflicts in the past focused on the appropriateness of one or more of these archetypes.

Filmmakers inevitably adapt to new codes, undermining their original purpose as they do so. As standards erode, critics call for new, stricter codes. In every era creative filmmakers learn to crack the codes, avoiding or at least blunting their restrictions. The process of circumventing codes often yields movie classics. In fact, many of the films that challenged prevailing codes are now recognized as classics, in part because filmmakers of necessity relied on inventiveness and adaptability in their efforts to thwart the codes. In order to attract audiences in the highly competitive film industry, producers managed through their own ingenuity to expand permissible limits, thereby further challenging and eroding the codes.

Not surprisingly, censorship wars erupt most often during periods of rapid social change in which pressure groups confront each other. At times, filmmakers choose to defy the Production Code, in effect refusing to submit to censorship. During the forties, fifties, and sixties a few producers defied the code and released unrated, uncensored films rather than submit to the changes demanded by the censors, generating controversies and affecting changes in the Production Code. In the long run, unrated films undermine regulators and may help affect changes and reforms in ratings systems.

Censorship Defined

Movie censorship exists in every age, and major censorship cases have occurred throughout film history. Censors may ban movies or, more often, may force film-makers to edit, remove, or otherwise alter or obscure words, behavior, or images. Censorship bodies police ideas, images, scenarios, situations, and language. Suppression may commence early in the production process, as soon as producers negotiate for the screen rights to popular novels or Broadway plays. Legal scholars label the attempts to influence films or other works of art prior to their completion as prior censorship or prior restraint. Postcensorship, on the other hand, refers to efforts to edit, rewrite, excise, or ban films after production. In the postcensorship system filmmakers may reedit and resubmit their movies. Both kinds of censorship have enjoyed popularity with regulators and censorship advocates at various points in history. And movie censorship still exists, although in altered appearance. Despite the U.S. Supreme Court ruling against prior censorship, Production Codes continue to define moviemakers’ boundaries.

Censorship subdivides readily into several distinct categories:

- Moral censorship. Producers remove or alter subject matter deemed “immoral” or contrary to prevailing moral codes.

- Political censorship. Censors ban or edit films containing references to sensitive political issues including unionization, communism, socialism, or depicting government corruption.

- Religious censorship. Films attacking or belittling religious organizations or leaders may succumb to religious censorship.

- Special interest censorship. Trade organizations or other powerful groups and individuals apply pressure to filmmakers to depict their self-interests positively and avoid negative depictions.

- Self-censorship. Producers often organize industry-dominated agencies to limit and censor films in order to forestall official government intervention in the film industry.

- Prior censorship (prior restraint), ruled unconstitutional in 1965, involves censoring movies while still in the production stages.

- Hidden censorship. Producers respond to hostile forces by altering or otherwise obfuscating censorable content even before submitting their films for ratings.

Sex

The moment motion pictures arrived in theaters, opposition to sexual depictions in movies crystallized. During the eighteen nineties and nineteen hundreds pioneer filmmakers routinely deleted or obscured nudity and seductive dancing to placate censors. Later, the sexy “pre-code” films produced from 1930 through the summer of 1934 presented sexual relations fairly realistically, as normal, natural events. Seductresses played by Clara Bow, Marlene Dietrich, Jean Harlow, and Mae West made indelible impressions on audiences. Eventually the Hays Code banned the kinds of characters they depicted. Thereafter, promiscuity, adultery, miscegenation, prostitution, homosexuality, and nymphomania appeared in films only obliquely, through innuendo, symbolism, and double entendre. In the nineteen sixties, in response to the relaxing of earlier censorship, sexuality once again appeared in films, openly depicted by characters played by Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and Jane Russell.

Today movie sexuality constitutes cinema’s most controversial issue. The current Production Code proved vigilant in protecting teenagers from frank, realistic depictions of sexuality and sexual relationships. Currently, only small independent studios risk making realistic depictions of sexual relations, creating a two-tiered system with only a handful of filmmakers willing to undertake the risks of having their films banned from mall theaters, video rental outlets, and large retail outlets. Therefore, the Production Code itself is responsible for...