eBook - ePub

Environment, Development, Agriculture

Integrated Policy through Human Ecology

This is a test

- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Summarising the democratic experience in modern Western civilisation, this text defines the term and looks at its changing meanings over the past two centuries or so. It records criticisms, and is especially concerned with the conditions that are necessary for democracy to exist.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Environment, Development, Agriculture by Bernhard Glaeser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

PART ONE

A theoretical paradigm

CHAPTER 1

An outline of human ecology

This chapter sets out to provide an introduction to human ecology. The intention is to acquaint the reader with the substance and problems of this still young science. In so doing, attention is given to a portrayal of so-called established knowledge, but also to the author’s own point of view. The following questions will be dealt with in detail.

What is human ecology? §1.1, “The concept and its delimitation”, is concerned with the starting point of human ecology in “environmental science”, on the one hand, and ecology, to which it owes its concept, on the other. In addition, Chapter 1 shows how human ecology can be incorporated into various other scientific disciplines.

What can human ecology do? What will it do? §1.2, “Goals and methods”, deals with the subject matter of human ecology – the relationship between humans and the environment, its application in various fields of work, and the methods used in dealing with human ecology concerns.

To bridge the gap between theoretical and methodological issues, it is often useful to design and employ conceptual models. A variety of such models are scrutinized in §1.3, ranging from those with a purely biological orientation, and thus of limited validity for human ecology, to models that take social aspects into account and thus have greater relevance.

1.1 The concept and its delimitation

Environmental science – the starting point

The applied natural sciences have had some success in finding technical solutions to environmental problems – particularly air, water and soil contamination – since these problems were first brought to public attention. In the USA, environmental awareness had already begun to take hold by the mid-1960s, followed by western Europe in the late 1960s and by most of the former socialist and developing countries only after the first United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) in Stockholm in 1972. The social sciences, which entered the field of environmental research even later, have also produced considerable results, for instance in the areas of environmental economics and awareness, social indicators, politico-administrative implementation and mediation between the interest groups involved. In all areas, remedial action taken against existing damage is in the foreground.

Since the oil crises in the 1970s, political pressure for the introduction of preventive measures has been increasing steadily. Among other things, this has resulted in greater emphasis being placed on basic environmental research. Examples from the natural sciences include energy use, the impacts of waste energy and ecosystem research. Basic research in the area of environment is still not prevalent among the social sciences, although some beginnings have been made. Consider, for instance, the question of social impacts of environmental policy measures or the range of theories covering everything from the social to the defensive costs of environmental protection.

It is here that the field opens up for human ecology, a basic research discipline located somewhere between the natural sciences and the social sciences. Its subject matter is the structure of the relationship between humans and nature, or society and environment. If one emphasizes the society-environment aspect, with particular reference to environmental damage as the starting point, then human ecology is primarily political ecology and, as such, its methodology will be clearly orientated towards social science, although some elements of natural science still have an important role to play. This is the concept supported here. Conversely, if one emphasizes the ecology aspect of human ecology, tying it more closely to the biological sciences, then obviously methodological elements of natural scientific study will move into the foreground of the research.

In any case, human ecology is not to be regarded as typical in the sense of conventional, compartmental university scientific research disciplines; rather, it introduces an epistemological element, an intellectual interest (Habermas: Erkenntnisinteresse), which tends to unify scientific disciplines. Enzensberger’s critical assertion emphasizes this difference: “First of all, human ecology is a hybrid discipline in which natural and social science categories and methods must be applied concurrently, without any theoretical explanation of the resulting complications” (Enzensberger 1973: 1; see also Bruhn 1974, Young 1974). This means that the subject matter of human ecology must be defined and that adequate methods be developed. The hypothesis that nature is exploited as an economic resource provides the occasion for such innovative efforts.

From ecology to human ecology

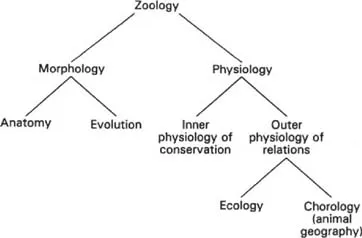

The first definition of ecology was given in 1866 by Haeckel, a prominent German biologist (1834–1919): “Ecology is understood as the entire science of the relationships of the organism to the surrounding outside world, which, in the widest sense, can be taken to include all the conditions of existence” (Haeckel 1866: 286).1 In his inaugural lecture in 1869, Haeckel made use of this definition of ecology as the basis for organizing the zoological sciences under one system (Haeckel, 1870: 364 f.). Here, Haeckel understands ecology to be the “science of the economic management of the faunal organism household”, which investigates the “totality of an animal’s relationships to its organic and inorganic surroundings”2 and forms a branch of the “outer” or “relation physiology”, which deals with the relationship of the organism to the outer world, as opposed to “inner” or “conservation physiology”, which treats the functions of the organism as such, namely self-preservation, growth, nutrition and reproduction (Fig. 1.1).

Contemporary natural science ecology proceeds from the concept of biosphere, defined by E. Suess in 1875 as essentially the entire living area of organisms that inhabit the surface of the Earth.

A given section of the biosphere with all its living and non-living components is labelled an ecosystem. The size of this biospheric section is not defined. All the organisms in the world together with their environment make up one large ecosystem, the biosphere. In 1877, Möbius introduced the concept of biocenosis for the living part of the ecosystem, organisms in their entirety, whereas the non-living part of the ecosystem was referred to as biotope or habitat (Bornkamm 1971: 467).

Human ecology is a growing field of academic and practical interest. In dealing with the different relationships and interactions between humans and the environment it involves a wide variety of academic disciplines and policy fields. The growing concern in both areas of expertise is reflected in the increasing number of college and university courses, and national and international conferences on the subject.

The international conferences have taken place on an annual basis: 1989 in Scotland, 1990 in Japan, 1991 in Sweden, 1992 in the USA, 1993 in Austria and Mexico, and in 1994 and 1995 in the USA again. These conferences usually combine a multitude of subjects and focus areas, and they attract academics from the natural, social and planning sciences as well as environmentalists and politicians.

Figure 1.1 The organization of the zoological system according to Haeckel (1870).

More than any other human ecology society, the Commonwealth Human Ecology Council, GHEC, based in London, exerts quite a bit of political influence through its environmental and developmental work in its member countries. Through its membership and via conferences, CHEC fosters exchange between high-ranking academics, foreign diplomats and politicians, including heads of state.

Apart from CHEC, there are other national and international human ecology societies in North America, Europe, Asia (including large countries such as China, Japan and India), Latin America and Africa. The German Society for Human Ecology (DGH), to give an example, was founded in 1975 and extends its membership to include Switzerland, Austria and Belgium. The DGH holds annual workshop conferences on specific themes such as gerontecology, a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part One A theoretical paradigm

- Part Two Ethical–political dimensions

- Part Three Implementation: two examples

- Part Four Consequences for future thinking and action

- References

- Index