![]()

Why Change Defensive Tactics Training | 1 |

The best defense against a surprise attack is not to be “surprised.”

—Bruce Lee

Bruce Lee’s Fighting Method Basic Training, 1977

The subject of force and law enforcement has always been one that seeks constant improvement. Dealing with rapidly evolving situations, law enforcement personnel have had a variety of tools and skill training provided to them over the years. Some have been effective, and some have provided poor or mixed results. This quest for the most effective method of dealing with aggressive behavior is constant as our times and technology evolve.

The concept of police defensive tactics is a relatively new approach to the police and physical encounters. Basic police academy provided some training in such things as punches, kicks, dealing with choke-holds, and grabs. There was training in the handheld weapons such as a baton to deal with more aggressive subjects, but the idea of on-going training and improved training was not truly developed before the 1980s. New recruits were expected to already have had some kind of skill training in that area whether it came from the military or they earned it on the street. However, it was presumed that if you wanted to be a police officer, then you would have the ability to handle yourself in a physical encounter. However, the further police recruits moved from World War II, the Korean Wars, and the Vietnam War, the less likely a new recruit would have this skill set. There was also a shift in the hiring practices, and in an effort to become more professional, police departments sought more college graduates rather than people with military experience.

In the early 1990s, the Los Angeles Police Department set out to make a defensive tactics program that would encompass all of the skills that officers would need in facing the criminal element. They gathered martial arts experts in many different fields and brought them together to create this new and improved system. However, before they did that, they searched their use-of-force records to find the most common occurrences of force application for officers, as this would help determine what kind of techniques should be adapted.

The Los Angeles Police Department found the following situations:

1. The officer grabbed an individual by the arm, and the individual pulled away.

2. The suspect ran at the officer and attacked with arms and legs.

3. The suspect ran from the officer, which resulted in both officer and suspect going to the ground.

4. The suspect assumed a fighting stance but waited for the officer to approach.

5. The suspect was about to be handcuffed.

This resulted in the development of a program that included not only standard defensive tactics in punches and kicks but also ground fighting because that was often lacking in basic training programs for law enforcement. It is interesting to note that those same situations are prevalent today in suspect-police encounters.

The 1980s and 1990s saw the development of many effective defensive tactics programs that were based on practical street applications and experiences. Some of the major development programs were ones like Bruce Siddle’s Pressure Point Control Tactics, which were adopted by many departments as basic academy defensive tactics training. Modern Warrior in New York created many realistic training opportunities by bringing more realism to the training and developing ground fighting and weapons training. Tony Blauer introduced his SPEAR technique to deal with the sudden assault situations that officers may face. FORCE created a, by the numbers, method of dealing with active aggression during arrest or violent encounter situations. Many other innovative programs were developed as well during this time. It seemed that the field was rich in the development of effective training for officers to deal with active aggressive suspects. Even so, with all of this development and skills, there were times when officers found themselves on the losing end and their skills failing them. The training and techniques were sound, so where was the weak link?

Law enforcement personnel did not always have to rely on just their hands to take on aggressive suspects. Throughout the years, different tools have been provided to them, which the public supported. The most common tool, of course, was the baton, which has evolved over the years from a wooden stick to the martial-arts-inspired PR-24 to the now metal collapsible baton. Once items such as saps and sap gloves were permitted, but these have been banned by most departments today. Even the flashlight was used as an impact weapon if the situation called for it. Many officers carried three and four D-cell flashlights that provided the required light at night and could be used as an impact weapon, but now that tool has been replaced by the smaller and more powerful tactical flashlight. The creation of mace was thought to be the new “self defense in a can” tool, but its effectiveness was very limited, as officers and suspects alike were usually sprayed and felt its effects.

Today, two options seem to be the preferred methods of many departments: the OC spray or pepper spray, which has mixed reviews from different sources and agencies, and the taser, which also has its supporters and opponents. As we look at such things as OC spray and the taser, officers are afforded the ability to diffuse a violent confrontation with these aids. However, these tools are not 100% effective, as many cases will attest. Because of that, officers must be ready and prepared to go to alternative force options to deal with the aggressive behavior. Officers still are acutely aware of the need for physical techniques that will enable them to go hands on with a suspect, and with that, there is a greater potential of injury not only to the suspect but also to the officer.

An interesting experiment conducted by Modern Warrior in New York revolved around the effectiveness of OC spray. They had volunteers who agreed to be sprayed with OC spray directly in the face. After the OC spray was sprayed on the face, the volunteers were given the task of walking the length of a pool, grabbing a knife placed on a table, and stabbing a target. In theory, OC spray should have made that very difficult for the volunteers to accomplish; however, during the test, they found that all of the participants were able to accomplish the mission, which put into doubt the ability of OC to be as effective as advertized, when the person has a goal or mission to accomplish.

While the taser has been the most effective “self-defense in a can” system to date, even this has some weakness. If both of the barbs from the taser do not encounter the subject’s body or if the subject is wearing heavy clothing, the contact between the two barbs may not occur. Information has also been found that some inmates in prison practice twirling their shirt to catch the barbs, so that when they get out of prison and encounter this tool, they can counteract it. No tool is ever foolproof, and that is why officers need to be as complete as they possibly can be, when it comes to force options.

Officers receive empty-hand techniques training while going through their academy, and those skills are often enhanced with in-service training or even supplemented with training on their own. For a time, the use of force continuums helped to direct an officer’s use of force when dealing with a rapidly evolving situation and authorized him or her to follow the plus one rule of being able to use one level of force above the resistive behavior. This type of training helped provide an understanding for the public and officers alike. Although the force continuum allowed for differences in officer’s size and other such factors, it did not take into account an officer’s emotional state at the time of attack.

Force continuum

Deadly force

Impact weapons

OC spray and taser

Hands-on techniques

Verbal commands

Officer’s presence

The emotional state of an officer can have a major effect on whether or not the training that he or she had received and the techniques that he or she had learned will be effective. For example, an officer who may be like the Biblical David, who had to face Goliath, would find it unnerving perhaps to confront the huge Goliath in a head-to-head physical altercation. Following the force continuum, the officers should be able to go one level up and utilize some of the tools that have been provided to assist them, such as the taser, baton, and OC spray. However, what happens when there is not enough time to respond with one of the tools that an officer has readily available or the tool is ineffective when deployed, and as a result, the officer must rely on his or her hands-on techniques and skills? Will those skills be able to overcome the advantage of the aggressor? If the officer does move beyond that force level to a higher one, will it appear to the public that the officer is now using excessive force? The video camera that views an officer’s actions will only see the action, not what the officer is experiencing, and this is an area that is left unexplored.

The issue of panic can cause multiple problems in a physical encounter. When someone is faced with a situation that his or her brain cannot analyze and cannot provide a suitable solution to, the brain freezes and so does the officer. A simple example is when you find yourself out somewhere, say at a shopping mall, and you come across someone you know. Their face is very familiar and you know him or her, but still, you cannot remember his or her name. The harder you try to remember the name, the less you are able to remember. This is a form of panic. Now, after the person leaves and the situation returns to normal, suddenly you can remember their name. This is how the brain works when we are panicked. Under great stress, solutions are not found because the conscious mind is overwhelmed with the situation. When this happens in a physical encounter, it can have devastating results.

Most police defensive tactics training programs treat officers in a “cookie-cutter” fashion in that one technique fits all, no matter the size or stature of the officer. The problem develops when an officer is required to execute a technique that his or her body is telling him or her to abandon. For example, imagine that you are faced with an opponent who is much larger than you are. If this subject charges you, do you truly want to meet him head on? Isn’t there a moment where the natural thing to do is to retreat away from the charge? This is why some techniques, while valid and effective, fail in the execution. The body goes in one direction and the mind tries to steer it in another, which results is poor application of the technique.

The secret is to have the mind and the body on the same page, and then, the application of the technique will be more effective, and there will be a greater chance of stopping the aggressive behavior without injury. However, when you are David and facing Goliath, getting both the body and mind in sync can be a problem. In addition, the time needed to respond could be under seconds, leaving little time to process the attack and form an effective defense. Remember that the attacking suspect has the initial advantage, because he knows when he is going to launch his attack, and the officer must process this and then form a response, all of which takes time.

Basic police training in defensive tactics teaches the principle of the reactionary gap. This creates time on the side of an officer to notice an attack and form a response to the attack, allowing the officer to use distance to give him time. The closer an officer is to a suspect, the less time he will have to react to an attack. Therefore, good tactics teach that the officer needs a good distance, and the further the distance, the more time an officer will have to perceive the threat and respond to it. The recommended distance is about six feet. Although this sounds good in training, in reality, this distance is usually much closer on the street. Just imagine if all police officers stood six feet away from people they were dealing with. How friendly would that department seem, and would the community feel that they are truly fulfilling their needs? The whole concept of community-oriented policing is for officers to become more involved in the community, and this is not truly possible with a six feet standoff zone. Therefore, while this may be tactically sound, it is not going to be possible for an officer on the street because of the assignment and mission that he or she delivers to the public. While the six feet standoff area may be impractical, the officer should make use of what distance he can, to allow him to formulate a response to the attack—even a few steps will aid in dealing with a rapid attack.

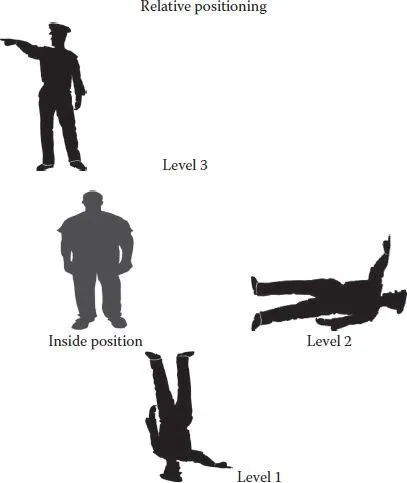

Another basic tactic taught to officers is relative positioning. The concept comes from the work of James Morrell and one of his students, John Desmedt. Morrell designed the principle called the Three Levels of Avoidance, which gave a numbering system to guide officers on dealing with a subject and where backup officers could take better tactical positions. In this system, the position directly in front of a subject was named level three, as this is where the officer is open to all of the physical weapons that a person may possess. The position standing next to the subject on either side was level two, which is a good one for an escort or control position, and the position directly behind a subject was called level one, which presented few weapons from the subject but gave the officer the advantage of gaining control (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 This chart demonstrates the three positions in the concept of relative positioning. Notice that the officer stays away from the inside position on the suspect to avoid being directly in front of the primary weapons of the suspect. (Courtesy of pixabay.com.)

Desmedt changed this a little by calling the position directly in front of a subject as the inside position. Then, he adjusted the positions around a subject to being slightly off center but still in front as being level 1; level 2 was the same as Morrell’s, and this was from either side, but Desmedt added a level 2 and a half, which is where the officer is slightly offset but at the rear of a subject. Level 3 as per Desmedt was where the officer faced the back of the subject.

The ideal position for an officer for talking to someone on the street is to stand slightly off center of a...