eBook - ePub

Transforming the Latin American Automobile Industry

Union, Workers and the Politics of Restructuring

This is a test

- 250 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Transforming the Latin American Automobile Industry

Union, Workers and the Politics of Restructuring

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This study looks at union responses to the changes in the Latin American car industry in the last 15 years. It considers the impact of the shift towards export production and regional integration, and the effect of political changes on union reponses.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Transforming the Latin American Automobile Industry by John P. Tuman,John T. Morris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Modern Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | The Transformation of the Latin American Automobile Industry |

Introduction

In the early 1980s, many analysts remained optimistic about the possibilities for growth in the Latin American automobile industry. Producing more than one million vehicles in 1980, Brazil became the eighth-largest automobile manufacturer in the world. In that same year, Mexico manufactured more than 500,000 cars and trucks, establishing new records in production and domestic sales; Argentina posted strong gains in sales as well. Against the backdrop of market saturation in Western Europe and the United States, Latin America appeared to be emerging as a large, dynamic market for automobiles.

The emergence of the debt crisis in 1982, however, dramatically altered the course of growth and development in the industry. The spread of the crisis generated a severe recession throughout Latin America, causing sales and production of finished vehicles to plunge to very low levels. The implementation of governmental austerity measures in the wake of the debt crisis only served to reinforce the stagnation of the industry. Faced with recession and uncertainty about the future, transnational firms responded by imposing layoffs, wage restraint, and other policies designed to reduce costs and boost productivity. By the close of the decade, however, companies in selected countries were increasingly shifting toward production for export markets, a project that enjoyed strong support from their host governments, the IMF, and the World Bank. More recently, governments throughout Latin America have liberalized trade in automobiles and parts, reshaping the industry in the process.

The trend toward restructuring and export promotion has produced significant challenges for workers in the Latin American automobile industry. Layoffs and reductions in real wages and benefits have threatened the traditionally privileged position of many automobile workers. Beyond this, however, workers have been confronted with demands for sweeping changes in the preexisting framework of industrial and labor relations. Company managers have argued that quality standards and productivity must be increased to globally competitive levels in order to meet the challenges posed by liberalization. As a result, firms and state elites have sought reforms in labor laws and work rules that would permit the introduction of team concepts, pay-by-knowledge compensation, and other practices associated with the Japanese, or “lean,” model of production.1 Nevertheless, since flexible production systems have directly challenged the power of unions to mediate conflicts and power relationships on the shopfloor, workers and union leaders have faced difficult choices about how to respond to these changes. In some cases, unions have attempted to adapt, create a new role for themselves, and negotiate concessions in exchange for restructuring. In other cases, however, unions and workers have resisted change and sought to preserve work rules and gains made during previous periods of development.

This book focuses on the transformation of the Latin American automobile industry. It discusses the factors compelling firms to introduce reforms and export production in the sector, and it explores the variation in responses that unions and workers have adopted to such changes. The case studies were drawn from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela. These countries were selected because of the size of their automobile industries, and because of their potential to illustrate meaningful contrasts in workers’ responses to liberalization and industrial restructuring. The overall goal of the project is to assess recent changes in the industry, and to do so in a way that facilitates comparisons with other sectors that are experiencing industrial transformations.

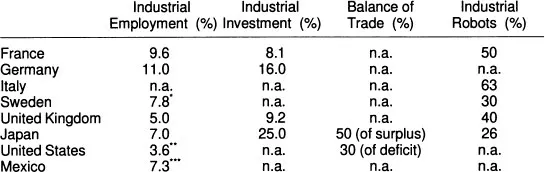

The transformation of the Latin American automobile industry has important public policy implications for the region’s new democracies and liberalizing regimes. Given the size of the industry and its links to other sectors, the performance of the automobile industry often affects industrial employment and growth in the manufacturing sector as a whole (Arbix 1995, 141; Novick and Catalano, this volume; Table 1.1). Moreover, there are strong reasons to suppose that the types of strategies that unions and workers have adopted in response to restructuring have affected the performance of the industry. Indeed, an emerging body of literature has suggested that the degree of union resistance or accommodation to restructuring partially influences the overall success (or failure) of economic reform efforts, both in the automobile industry and in other sectors (Nelson 1992, 245–49; Humphrey 1992, 328–9; Tuman 1994a; Towers 1996, 5).

Table 1.1

Economic Impact of the Automobile Industry in National Economies: 1980s and 1990s

*Estimated using OECD total employment figures for 1994, with data provided by Ruigkrok et al. (1991).

**Estimated using 1994 sectoral data from the American Automobile Manufacturer’s Association, Motor Vehicle Facts and Figures, 1996, and OECD figures for 1994.

***Data for Mexico are preliminary figures for 1993, and were obtained in INEGI, La Industria Automotriz en México, Edición 1995.

While analysts have recognized the importance of the changes occurring in the Latin American automobile industry, most studies have not explored the roles of workers in the processes of adjustment and restructuring (e.g., Lee and Cason 1994). Indeed, the last surveys of labor in the Latin American automobile industry were completed in the mid-1980s, prior to the reforms that transformed the industry’s structure and its systems of labor relations (Kronish and Mericle 1984a; Jenkins 1987). Moreover, much of the recent literature has tended to focus only on single cases, neglecting the contrasts in development outcomes across different Latin American countries (Mortimore 1995; Deyo 1996). As one step in filling this gap in the literature, this volume includes several comparative studies of labor in the Latin American automobile industry, with a focus on the period of 1980 to 1995.

In the remaining sections of this chapter, we provide an overview of changes in the Latin American automobile industry. The chapter begins with a discussion of the development of the industry during the period of import-substitution industrialization (hereafter, ISI), and then analyzes the trend toward restructuring. We then compare selected countries in Latin America to one another, and the industry in Latin America to other regions in the world, exploring the contrasts in patterns of investment, production, and compensation. The final section provides a brief summary of the findings of the country-studies, and attempts to connect those findings with some of the current themes in the literature of comparative industrial relations and political economy.

Historical Overview

The Latin American automobile industry has gone through three clear phases of development and performance since the 1920s: (1) import-substitution industrialization (ISI, 1930–1960); (2) a transitional phase that sought to deepen industrialization while maintaining the protectionist policies characteristic of ISI (1960–1982); and (3) economic crisis and liberalization after 1982. In what follows, we briefly analyze the main tendencies in each of these periods, giving particular emphasis to the structure of the industry and its systems of labor relations.

The Early and Mature Phases of ISI

Transnational automobile firms entered the Latin American market in the beginning of the twentieth century. At first, most companies exported finished vehicles to countries exhibiting strong market potential. However, by the late 1920s, changes in trade and industrial policies in Latin America quickly forced the major producers to establish assembly operations throughout the region.2

Automobile production was initiated in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico between 1916 and 1935, when the major firms, based primarily in the United States, starting exporting completely knocked-down kits (CKDs) for assembly by domestic workers. Ford began operations in Latin American prior to its competitors, establishing assembly facilities in Argentina in 1916, Brazil in 1924, and in Mexico in 1925 (Meza 1984, 25; Jenkins 1987, 18). By the 1930s, General Motors had initiated production in Mexico City and other areas as well. In large part, the decision to import “kits” for assembly had been prompted by new tariffs that made domestically assembled vehicles far cheaper than imported ones (Jenkins 1987, 19). However, since most Latin American countries lacked the technology and infrastructure required to produce automobile parts, firms found it necessary to import kits for assembly instead of manufacturing vehicles in these countries. Throughout much of the early phase of ISI, the initiation of assembly generated a modest growth in industrial employment, but failed to stimulate the development of a domestic automobile parts sector. Indeed, between 1940 and 1947, a high percentage of spare parts and materials used in assembly continued to be imported from abroad (Jenkins 1977; Hinojosa-Ojeda and Morales 1992, 403–4).

The second period (1960–1982) was characterized by governmental efforts to “deepen” the ISI model throughout the region. A much smaller number of transnational producers emerged in the post-World War II era, and competition in foreign markets intensified among the American and European producers. At the same time, state regulators moved to impose new trade and industrial policies on the sector as a result of ongoing concerns regarding the absence of a domestic parts industry and chronic balance-of-payments problems (generated by automotive parts imports). In many cases, these regulations created domestic parts industries by imposing restrictions on imported inputs, and by implementing domestic content requirements and new investment rules (Bennett and Sharpe 1985, 94–6, 129–51; Jenkins 1987, 22–3; Shapiro 1991, 878–89).

The basic framework of labor relations was also consolidated in the automobile industry during this period. Transnational firms operating in Latin American introduced industrial relations systems that partly conformed to the norms established in advanced countries. Often termed “Taylor-Fordism” (or “peripheral-Fordism”), this system was characterized by highly elaborated systems of job and skill hierarchies, combined with multiple categories and grades, a strict respect for seniority, and relatively high wages (Lipietz 1987, 70–9; Jenkins 1987, 78–9; Jessop 1990). In the context of the Latin American, however, Fordism aimed at securing the discipline of workers, and was not, strictly speaking, linked to productivity growth. In Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, Fordist systems were implemented and reproduced through the medium of state-corporatist3 unions that had direct ties to a hegemonic political party or the state bureaucracy.

For a variety of different reasons, governments were confronted with the exhaustion of the ISI model by the beginning of the 1970s. In the first place, the perpetuation of income inequality throughout Latin America limited domestic demand for automobiles. In addition, the combination of many producers, and the proliferation of large numbers of product lines, limited the potential growth of the industry. As a result, most producers were unable to achieve economies of scale (Kronish and Mericle 1984b, 276–7). These problems were compounded by the continuation of balance-of-payments problems generated by automotive imports. In response, transnational producers began to pressure policy makers for greater market access and for reduced trade restrictions on capital goods and parts imports. However, national components manufacturers—which had been nurtured (and even created and owned) by national governments—opposed these measures. In Mexico, the compromises reached in the 1970s specified that capital goods imports could be increased, but that their value had to be offset in exports of vehicles. Restrictions on the number of models were eliminated, but domestic content requirements were maintained (Bennett and Sharpe 1985).4

Latin American countries generally resolved the dilemmas posed by ISI by borrowing abroad, particularly after 1973, when international banks sought outlets for the massive deposits of petro-dollars made by oil-producing countries (Frieden 1991). Nevertheless, by resorting to more debt, policy makers only postponed difficult choices involving the resolution of the structural problems of the ISI model. After a decade of accelerated borrowing, rising international interest rates, combined with a fall in world oil and commodity prices, undermined the capacity of Mexico (and several other heavily indebted countries) to meet their debt service obligations. Mexico informed its lenders in New York in August 1982 that it would not be able to pay interest on its debt. This caused panic throughout the financial sector as it became evident that other regional borrowers, like Argentina, Brazil, and Peru, were in similar danger. The response by private financial institutions of temporarily denying further lending plunged the region into crisis and initiated the so-called década perdida (lost decade). Faced with the complete collapse of a long-standing model of growth, with little hope for restoration, Latin American countries abandoned state-led development and ISI, and began the process of structural adjustment and economic liberalization.

The Impact of the Debt Crisis

In the aftermath of the debt crisis, the cessation of lending and the introduction of austerity measures provoked a strong recession throughout Latin America. As a result, sales and production of automobiles fell in Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and several other countries. Despite some improvements by mid-decade, production in Brazil and Argentina contracted by 5.5 and 28 percent, respectively, between 1985 and 1990. Mexico was one of the few cases to post gains in this period. In any case, growth in the region was restored definitively only in the early 1990s (see Table 1.2).

As noted previously, changes in domestic market conditions in the 1980s forced transnational firms to take drastic measures to shore up the profitability and competitiveness of the industry. Some firms reconsidered their participation in the region. For example, by 1986 Renault had decided to stop producing automobiles in Mexico, and also to reorganize its operations throughout Latin America. However, most of the other companies—including Chrysler, Ford, General Motors, Nissan, and Volkswagen—responded to the crisis by introducing a variety of different restructuring measures. For the most part, these policies involved reducing employment and growth in wages and benefits; introducing changes in the labor process to boost productivity and product quality; relocating production to new greenfield sites; selectively adopting just-in-time (JIT) production methods to reduce shipping costs and inventory; and, in some cases, the introduction of export production.

By the decade’s end, the emerging consensus around neoliberalism in Latin America led to the elimination of many of the trade and investment rules associated with ISI. Most governments privatized state owned vehicle and parts companies and abandoned investment laws that promoted domestic ownership in the sector. During this period, governments also embraced trade liberalization, lifting tariffs and quantitative restrictions on imported vehicles and automobile parts. In the aftermath of liberalization, many transnational producers in the terminal sector began importing parts from abroad, often with devastating effects for domestically owned parts producers. In addition, imports of new veh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Transformation of the Latin American Automobile Industry

- 2. The Argentine Automotive Industry: Redefining Production Strategies, Markets, and Labor Relations

- 3. The Transformation of Industrial Relations in the Brazilian Automotive Industry

- 4. Restructuring in the Colombian Auto Industry: A Case Study of Conflict at Renault

- 5. Economic Integration and the Transformation of Labor Relations in the Mexican Automotive Industry

- 6. The Political Economy of Restructuring in Mexico’s “Brownfield” Plants: A Comparative Analysis

- 7. Recent Development in the Venezuelan Automotive Industry: Implications for Labor Relations

- Bibliography

- About the Editors and Contributors

- Index