![]()

Part I

War and revolution

![]()

1 Imperial powers and pre-WWII Japan

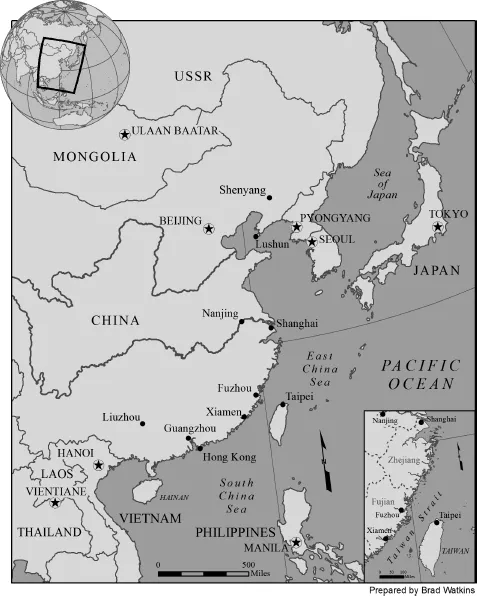

Since “East Asia” is in many ways a modern construction, it should not be surprising that in ancient time the areas we now consider a part of East Asia followed their own unique development trajectories. Wynn Gadkar-Wilcox points out that beginning around two millennia ago, a series of attempts at expansion and conquest from rulers in the North China Plain led to the diffusion of economic ideas, and these disparate places slowly began to share a common heritage.1 Throughout this area, over the course of many hundreds of years, East Asians in what are now China, Japan, and Korea developed patterns of social values, political sensibilities, institutional procedures, religious institutions, military strategies, and diplomatic behaviors which arose through centuries of change, revolution, war, and reform.2

These patterns include commonalities in centralized political institutions, the dissemination of works describing the values and political theories of the Confucian-Mencian paradigm, the spread of Buddhism, and a system of uniquely East Asian diplomatic relations which emerged from that paradigm. These civilizational patterns set a framework not only for the development and evolution of common pre-modern institutions but also for the modern development of East Asia. These common patterns informed economic expansion and reform efforts in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and intellectual responses to Christianity, global trade, and European gunboats from the sixteenth century through to the twentieth century.

This chapter begins with the major development of the principal civilizations and political institutions of East Asia from the ancient time to the pre-modern period about 1500. Then, it examines relations between East Asia and Europe from about 1600 to 1800. The Europeans rushed to East Asia with a spirit of adventure, fed primarily by the search for lucrative trading opportunities. To a lesser extent, they were also motivated by the evangelical zeal to spread Christianity to the “heathen” world.3 Thus, Western countries and merchants were often able to use Christian conversion to cover their true intention of commercial profit. Because of its complexity and international dimension, the European commercial and evangelical pursuit became an ultimate political test for all the East Asian countries.

In the seventeenth century, however, the Europeans were considered uncivilized since they did not know the classic texts, and were treated as other “barbarians” like some ethnic minorities. Then, the emergence of the French and British colonial empires in Asia in the eighteenth century brought the universality of East Asian classical civilization into question. East Asians began to see the French and British as possessing a separate civilization, rather than merely being uncivilized. The urgency of the military and commercial problems wrought by Europeans and Americans greatly accelerated East Asian efforts at political, economic, and technology reform. By the mid-nineteenth century, educational curriculum of Confucianism, political loyalty to the emperor, and native religions like Buddhism and Daoism (Taoism) came to be understood as part of Eastern tradition, and the alternative to them came to be seen as “Western modernity.” This particularistic world view gave rise to proto-nationalistic discourses throughout East Asia. This shift coincided with efforts at reform and social change in East Asian countries.

The second half of the chapter situates Japan’s experiences with industrialization in the indigenous context of the late nineteenth century while taking into account its progress, challenges, and problems. It reveals that the classic civilizations set a framework not only for the development and evolution of common pre-modern institutions but also for the modern development of East Asia. But it also explains why Japan’s economic success had soon turned the country into a militarist, aggressive East Asian power, and how Tokyo colonized Korea and Manchuria in the early twentieth century.

Classic civilizations and tributary system (from ancient time to 1500)

Through traditional institutions such as the civil service examination system (in China and Korea) and the samurai institution (in Japan), East Asian elites relied on universalistic systems of thought. What determined whether a people or culture was civilized was whether they knew certain canonical classic texts; whether they could read the works of Confucius (551–479 BCE) or Mencius (Men-tzu) (372–289 BCE) or key passages from the Classic of Ritual in classical Chinese, and whether they could make decisions about present circumstances based on consulting Chinese dynastic histories. The Confucian-Mencian paradigm is a complex system of moral, social, political, philosophical, and quasi-religious thought.4 During the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the Confucian-Mencian paradigm was adapted as ruling ideology, and Confucius’ four books became classics. Confucian ideas of meritocracy in part resulted in the introduction of the imperial examination system into traditional China. The imperial examination system evolved gradually from its origins in 165 BCE. At that time, when the Han emperor called candidates for public office to the capital for an examination of their knowledge of the classics, the examination was an irregular system of gaining office and an alternative to the usual system of appointment and recommendation of officials.

However, by the time of the Sui dynasty (581–618), Confucianism became more firmly re-established and operated as an ideology alongside Buddhism.5 The national examination had been established as a civil service system to test knowledge of Confucianism. Although the Sui emperors reunified the country, they squandered the treasury to build palaces for their own comfort and vanity. They attempted to re-conquer Korea three times, and several million peasant draftees served as soldiers and laborers for the military expeditions. As a result, the peasants were exhausted and the Sui treasury nearly empty. The burdens on farmers had become unbearable. They rebelled, dealing a fatal blow to the Sui regime. Li Yuan (566–635), one of the rebel leaders, assumed the imperial title at Chang’an and called his new regime the Tang dynasty (618–907).

Confucianism was revived by Zhu Xi (1130–1200), the greatest Confucian master of the Song dynasty (960–1279), in a doctrine that combined commentaries on classical Confucian texts with sensibilities and insights that may have been borrowed from Buddhism and Daoism.6 He developed methods and paths to reach goodness or become a “gentleman”; a concept Confucius and Mencius summarized in the Four Books. This focus on cultivating virtue helped students prepare for their civil service examination. The imperial examination system based on the Confucian-Mencian paradigm had been well established by the Song dynasty and continued until it was abolished in 1905. Under this system, almost anyone who wished to become an official would have an opportunity to become an officer, a position which would bring wealth and honor to the whole family, if he proved his worth by passing written government examinations. The domination of the civilian bureaucracy in military affairs contributed to the Song army’s defeats against the Mongol invading troops. In 1279, the Mongols destroyed the Chinese army, ended the Song dynasty, and established the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). Nevertheless, the Mongol emperors of the Yuan court adopted Zhu Xi’s commentaries on the Four Books for the civil service examinations in 1315.7

The Confucian-Mencian paradigm influenced not only China, but also Korea, Japan, and Vietnam during their classic and middle ages through international trade, travel, and cultural exchanges in East Asia. During the Yamato Period (350–710) in Japan, several kings sent missions to China to gain Chinese confirmation of their dominance. When they returned, they brought back knowledge of Confucianism, Buddhism, and the Chinese administrative system. After Silla conquered the other kingdoms in Korea, many war refugees refused to accept the unified Silla government and fled to Japan. Among them were many learned officials and highly-educated scholars who brought the Confucian philosophy and imperial administrative experience to Japan.8

One advantage of this universalistic focus was that one did not have to be ethnically Han to be considered civilized. Indeed, Korean elites saw the classic texts and histories as very much a part of their own civilization, and not as something “foreign” or “Chinese.” Moreover, non-Han peoples, including ethnically Vietnamese subjects of the empire, could pass the exams in China. The flexibility of this system allowed non-Han rulers such as the Qing to adapt to this system. Mark Elliot, for example, describes the Manchu-Han relations during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) as “ethnic sovereignty” which offered legitimacy for a dynastic central government to run multiple ethnicities in China.9

Before the European expansion in the 1500s, East Asian countries had established centralized dynasties to control their territories, maintained certain social orders, and developed domestic and international trade. Territoriality played an important role for the monarchical governments in the 1500s–1800s, including the Qing dynasty in China, Tokugawa Bakufu (1603–1868), and Choson Korea (1392–1910), allowing them to prove their legitimacy and authority, and to justify their military expansion and social control. According to Charles S. Maier, the term “territoriality” can be defined historically as bordered space (and the properties) under certain political control.10 In the modern European system of nation-states, “territoriality was the basis of establishing national identity, demarcating state boundaries, and conducting international relations.” Yet, Xiaoyuan Liu states that “territoriality did not start in modern time and was not a European specialty.”11

In pre-modern East Asian history, before the full-scale incursion of Western powers, according to Liu, all East Asian states inside the Sino-centric tributary system possessed territoriality, even though such territoriality differed drastically from the modern/European type. To cope with the international relations in East Asia, a tribute system was formed for conducting diplomatic and trade relations between China and other countries and steppe kingdoms such Xiongnu from the third through eighteenth centuries.12 Under this system exchanges of gifts between foreign rulers and the Chinese emperor were carried out. Foreign rulers including the Japanese, Koreans, and Vietnamese saw advantages to seeking a mutual relationship with the Chinese empire. They sent their representatives to the Chinese capital to present their tributes (exotic luxury goods, local special products, or people) to the Chinese emperor, and in return, they were rewarded with promises and gifts from the Chinese emperor, such as political recognition, non-aggression agreements, and gifts like porcelain and silk.13

The symbolism of the tribute system ensured that the Chinese emperor and the Middle Kingdom would be regarded as superior to their trading partners. Under this system, the Chinese emperor recognized the authority and sovereignty of foreign monarchs. He conferred upon them the trappings of legitimacy. In exchange, rulers from foreign lands, adopting a posture of subjugation, recognized the supremacy of the Chinese emperor and the legitimacy of universal civilization as understood within the Confucian-Mencian paradigm. This suzerainty over neighboring lands afforded exclusive trading conditions between East Asian countries and also implied Chinese military protection to the subordinate states. Therefore, all diplomatic and trade missions were construed in the context of a tribute relationship. Under such a system, there were asymmetrical power relations between China as the Middle Kingdom and its surrounding subordinate states. In this system, power diminished with the cultural and geographical distance from the Middle Kingdom, so that Korea was placed higher than others, including Japan, the Ryukyus, and other Indochinese kingdoms that also gave tribute.14

Under the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), countries that attempted to establish political, economic, and cultural relationships with the powerful Chinese empire had to enter the tribute system. To keep it official, for a short period, the tribute was actually the only existing element of foreign trade for China. Hongwu (reigned 1368–1398), the first Ming emperor, prohibited any private foreign trade in 1371. To increase the number of tribute states, the Yongle Emperor (r. 1402–1424), expanded the tribute system by dispatching massive overseas missions to the South Seas in the early fifteenth century. The overseas expeditions of Zheng He (1371–1435) carried goods to build tribute relationships between the Ming dynasty and newly discovered kingdoms in Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Eastern Africa is an example of the success of this philosophy.15

The tribute system had been challenged and interrupted from time to time. During the Han dynasty, for example, Xiongnu came to regard the system as a fraudulent and empty agreement, and chose to utilize the act of tribute with such frequency that it reaped enormous rewards for the subsidiary state. China recognized the disingenuous attitude on the part of Xiongnu and suspended the tribute relationship. In another situation, when there was a war between two tribute states, China was held to its own end of the bargain. The Japanese invasion of Korea in the 1500s is an example of this. Upon the landing of Japanese militants throughout Southeast Korea, the vassal state requested prompt intervention on the part of Ming China in recognition of the binding tradition between the two. Korea had long been most faithful to the Chinese in the tribute system. The two countries had been closely connected since Korea became independent during the disunity of the third through fifth centuries, and China realized that the time had come to uphold its agreement.16

The Chinese tribute system, with its burdensome, ritualistic mannerisms, continued until the Qing dynasty when European merchants began arriving. Because Confucian culture placed a greater reward on non-economic functions rather than extra profit, the Chinese preferred to continue tribute customs even when Western merchants began to arrive at the Chinese coast to trade with China. The Chinese were willing and able to extend to Westerners, as “...