![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

PURPOSE OF THIS BOOK

Books, articles and academic papers on executive remuneration have become increasingly common in the last ten years. They are written by economists, lawyers, consultants and journalists. You find them in newspapers, business weeklies, human resources (HR) practitioner magazines and academic journals. They fall into various categories. Some are sensationalist, others apologetic. Some are highly theoretical and beyond the reach of those without an extensive knowledge of economics.1 Few achieve a balance, combining a practical view with an intellectual underpinning. That is the objective of this book: to explain in an intelligent, unsensational and balanced way how modern executives are paid – and why.

Is it possible to reach an equilibrium point, where senior executives, shareholders and companies are happy?

The executive pay question has many facets. Consider the following. Why has executive pay increased so much since the early 1990s? Why is executive compensation, as they call it in the US, typically higher than it is in the UK, which in turn is generally higher than the rest of Europe? Why is the average remuneration of executives in France higher than it is in Germany? Why are Swiss executive reward levels comparable only to those found in the US? Why are equity plans uncommon in Japan? Why have some companies discovered that their long-term incentive plans pay out significant sums at times when their share price is falling? Why have remuneration committees recommended pay proposals which have subsequently been roundly rejected by shareholders? Why are details of directors’ pay disclosed in great detail in the UK while many German companies still resist giving such information?

During the course of this book I will try to answer these specific questions. At the same time I will address the biggest question of all: is it possible to reach an equilibrium point – where senior executives are generally happy with their pay, shareholders are generally happy with what their senior executives are being paid, and companies believe their leaders are properly motivated and incentivised?

BASIC MODEL

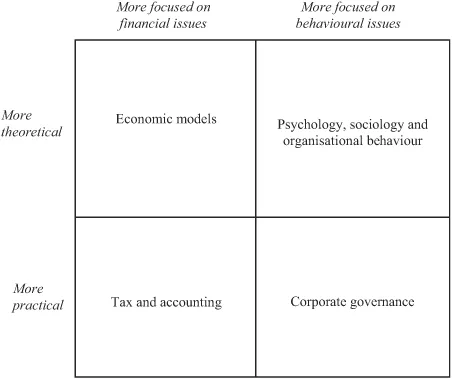

The conceptual framework used here is the consultant’s four-box model (see Figure 1). It groups the issues into four categories. The first two categories, in the top left- and right-hand boxes, deal with economic models, psychology, sociology and organisational behaviour. These are the more theoretical parts of our examination of executive reward – the parts most commonly the subject of academic research. In the bottom left- and right-hand boxes are tax and accounting on the one hand, and corporate governance on the other. These are the more practical aspects of our examination: the domain of practitioners – compensation and benefits specialists, lawyers, accountants and so on. Looking at it in a different way, the left-hand column focuses primarily on financial issues; the right hand column focuses primarily on behaviours.

Summary: This book looks at the theory (economic and behavioural) and the practice (tax, accounting and corporate governance) that inform decisions about executive pay.

Figure 1 Factors determining senior executive reward

The four categories, proceeding clockwise from the top left-hand corner, are each the subject of a separate chapter. The aim of the final chapter is to bring the various ideas together into a single set of principles and best practices.

TWO ASSUMPTIONS

Before we begin we need to make two key assumptions that underpin the analysis which will follow in subsequent chapters.

People are both rational and irrational … psychological factors are at play as well as reason when it comes to executive pay.

The first assumption is about the nature of humankind: what causes us to do the things that we do? The economists’ traditional assumption is that people are rational and self-interested. They take actions with the intention of maximising personal utility, typically thought of primarily in monetary terms, and over the short run in preference to the long run. A more sophisticated approach is proposed by Michael C. Jensen of Harvard Business School. Jensen proposes that people are resourceful, evaluative and maximising:2 they are clever and creative; they want more of the things that they value rather than less; they make choices, trade-offs and substitutions; they seek to maximise the value of their goods, meaning here the things that they value, be they tangible or intangible.

Though persuasive in many ways, the resourceful, evaluative and maximising model of human behaviour is still deficient in one important respect: it rests on the presumption that people are always rational, and we know that this is not the case. People are both rational and irrational. There is a double loop in our mental processes: two sets of systems, one logical, the other psychological, are intertwined. We are resourceful, capable of evaluating situations and making choices. We are also emotional. We have needs. We are affected by the social environment in which we live. We are capable of acting altruistically as well as selfishly. At times we do things which even we cannot really explain. This model of human behaviour, a dualistic model which recognises that there are psychological factors at play as well as reason, is the one we shall assume as we examine various aspects of executive pay.

The second assumption is in response to the question ‘What is a company for?’ The often repeated phrase ‘to maximise shareholder value’ is in many ways inadequate because it places too little emphasis on the legitimate interests of other stakeholders – lenders, customers, employees and so on. The problem with stakeholder theory, which tries to embrace these other perspectives too, is that it fails to provide satisfactory mechanisms for evaluating the competing demands of different interests, leaving senior management unable to make purposeful decisions. A better view is what Michael Jensen and Kevin J. Murphy of the Marshall Business School at the University of Southern California call ‘enlightened value maximisation’ or ‘enlightened stakeholder theory’, which proposes that the proper objective of a company is to create (and ultimately to maximise) the long-run total value of the firm.3

Note the two important elements of this way of answering the question:

• Value is to be maximised in the long run, not the short run;

• It is firm value not shareholder value which is to be maximised.

This admits the legitimate interest in value creation of at least some other stakeholders, including top management and other employees. It is now widely accepted that, just as shareholders contribute financial capital to a firm, so management and employees contribute human capital, being the sum total of their knowledge, skill, experience, intelligence and so on. There are various ways of placing a value on human capital: for example, as a minimum (looking at it solely from the executive’s perspective) the human capital of a company’s chief executive officer (CEO) might be calculated as the net present value of his expected future earnings from his or her best alternative source of employment.

The enlightened value maximisation assumption can itself be derived from one of the fundamental principles of social welfare: society’s object is to maximise total utility, to create the greatest good for the greatest number, and to maximise the efficiency with which society uses resources to create wealth and minimise waste. What it does not do, however, is deal with the question of how value is to be allocated between different stakeholders, which is not a straightforward matter.

Although different stakeholders all have a legitimate interest in the value created by a firm, this does not mean that their interests are equal. One way of looking at the problem of allocation between stakeholders is like this. The interests of some stakeholders might be satisfied if they are simply kept happy, without direct financial compensation; this might be true, for example, for customers and for society in general. The interests of other stakeholders might be satisfied by a fixed-rate return; for example lenders and junior employees who are content to be remunerated solely by wages or salary – a fixed rate for the job in question. Some stakeholders, however, require an equity return – a share in profits – because they share a proportionate amount of risk; this includes not only shareholders, but also top management, given the amount of the human capital they have invested and the risks they run if things do not turn out for the best.

Although different stakeholders have a legitimate interest in the value created by a firm, this does not mean their interests are equal.

TWO DEFINITIONS

As well as making two assumptions, we also need two important definitions.

The first is what is meant by ‘senior executive’. Many books and articles on executive remuneration concentrate on the CEO. But a lot of the issues which apply to CEOs are common to a broader group of senior executives, including the chief operating officer (COO), chief financial officer (CFO), chief technology officer, head of sales and marketing, human resource director and so on. In the US this group is sometimes referred to as the ‘C suite’; in the UK and Europe, the ‘executive committee’, ‘general management committee’ or ‘executive board’; in France, the ‘directoire’; in Germany, the ‘Vorstand’; and so on. Changing trends in corporate governance mean that, while historically in the US and UK many of these individuals would have been main-board executive directors, it is increasingly common to find only the CEO and CFO on the main board. In Continental Europe, where it has been more common to separate supervisory and executive functions into a two-tier board structure, it is the executive board we are talking about. In short, we are focusing on the group of very senior executives responsible for defining and executing a company’s strategy, who through their actions are capable of directly affecting (positively or negatively) the company’s profits, share price, reputation, market positioning and so on.

By ‘senior executive remuneration’, we mean the total reward of key executives who are responsible for defining and executing a company’s strategy.

The second definition we need is what we mean by ‘executive remuneration’ – what the Americans call compensation or what might more commonly in Europe now be referred to as reward. Most executive pay packages contain four basic components: a base salary, an annual bonus typically tied to financial performance, an equity plan or some other type of long-term incentive arrangement, and a retirement scheme. In addition, executives participate in broad-based employee benefit plans and they may also receive special benefits, including enhanced life insurance and medical plans, use of corporate jets and chauffeur-driven cars. There may be other special terms of employment: for example, in the US the provision of formal employment contracts in contrast to the employment-at-will arrangements applicable to other staff. In the UK and Europe the special employment terms might include relatively long notice periods to protect the executives in the event of redundancy (though new corporate governance regulations are increasingly placing limits on long notice periods). Practitioners now refer to this bundle of rights, monetary and non-monetary, as ‘total reward’, and it is that which is the subject of this book.

NOTE ON CASE STUDIES

This book contains a number of case studies and other examples which are intended to illustrate the main concepts that are being described. None of these cases are fictional; most are drawn from public information sources, and only a few involve private knowledge. Nevertheless, in all instances I have tried as far as possible to make the cases anonymous while at the same time remaining true to the underlying facts. My reasons for this approach are various. In particular, my intention is not to comment on or criticise any particular company: other examples could equally well have been used. I am also well aware that there may be other relevant facts and circumstances, not obvious at first sight, which might explain the actions taken.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Compensation, Benefits and Incentives

This chapter describes the basic elements of executive reward – a base salary, an annual bonus, a long-term incentive payable in cash, shares or share options, a pension, and other benefits which may be delivered as cash allowances or in non-cash form. Compensation specialists and others with a good basic knowledge of executive compensation can if they wish move directly to Chapter 3. Others should read on. Note that much of the basic analysis contained in the first part of this chapter is based on the academic work of Kevin Murphy.1

SALARIES

Base salaries for senior executives are typically determined by benchmarking using salary surveys, often categorised by size of company and industry and supplemented by detailed analysis of comparator companies. Since salaries below the median are often labelled as below market, while those in the top two quartiles are considered to be competitive, the survey approach has contributed to a ratcheting-up effect in base salary levels over the years. Pay surveys do not generally take account of other criteria which many economists consider relevant for predicting earnings levels, including previous experience, qualifications and so on. Moreover, company size is at best an imperfect proxy for managerial skill requirements, job complexity and span of control.

Companies devote a significant amount of time to the salary determination process, even though salaries comprise a decreasing proportion of total compensation.

Companies devote a significant amount of time to the salary determination process, even though salaries comprise a decreasing proportion of total compensation. There are a number of reasons for this:

• Base salaries are a key component of executive employment contracts and a reference point for many other elements of reward: target annual bonuses are often defined as a percentage or multiple of base salary; defined pension benefits and severance arrangements also typically depend on salary levels;

• Senior executives who, like many other individuals, are often naturally risk averse will frequently prefer an increase in base salary to a corresponding increase in target bonuses or other variable compensation.

SHORT-TERM INCENTIVES

Annual bonus contracts are generally explicitly set out in a contract or plan, with at most a limited role for discretion. In some firms, boards can exercise discretion in allocating a fixed bonus pool among participating executives, but the flexibility in these cases affects only individual allocati...