eBook - ePub

Reducing Global Poverty

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reducing Global Poverty

About this book

This is the first volume in an ambitious new series-"Patterns of Potential Human Progress"-inspired by the UN Millennium Development Goals (MGDs) and other initiatives to improve the global condition. The first and most fundamental of these goals-reducing poverty worldwide-is the focus of this book. Using the large-scale computer program called International Futures (IFs) developed over three decades at the prestigious University of Denver Graduate School of International Studies, this book explores the most extensive set of forecasts of global poverty ever made-providing a wide range of scenarios based on an authoritative array of data. It transcends the "$1 a day" baseline measure of poverty and probes important concepts like income poverty gaps and relative poverty. The forecasts are long-term, looking 50 years into the future, far beyond the 2015 date set out by the MDGs. They are geographically rich, spanning the entire globe and drilling down to the country level, including one of the most important global focal points, India. The poverty forecasts in this book, and all the volumes in the series, are fully integrated in perspective across a wide range of human development arenas including demographics, economics, politics, agriculture, energy, and the environment. Full of colorful, thoughtfully designed graphs, tables, maps, and other visual presentations of data and forecasts, this large-format inaugural volume ensures that the "Patterns of Potential Human Progress" series will become an indispensable resource for every development professional, student, professor, library, and indeed, country around the world.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Global Poverty

Poverty, the inability to attain a “minimum” level of well-being, is the most fundamental economic and social problem facing humanity. In the extreme case, poverty actually kills people. Even when it does not kill, poverty is a basic deprivation that stunts the very possibility of human development. It is therefore stating the obvious to declare that the reduction and ultimately the eradication of poverty must be a central goal for the people on this planet.

Even before the widespread publicity associated with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by the United Nations, global poverty was understood to be a somewhat intractable problem. World Bank documents in the 1970s and 1980s illustrate the many efforts to analyze the state of global poverty and many proposals to reduce global poverty. However, with the increased emphasis given to the goal of poverty reduction in the MDGs, the measurement of poverty and its speedy amelioration have now become central to the efforts of the entire global development community.

There are deep moral motivations for a commitment to poverty reduction. To take one well-known approach, the Rawlsian principle of justice as fairness leads directly to the consideration of the state of the poor and a commitment to improve their lives. More recently, the Nobel laureate Amartya Sen advanced an even broader concept. According to Sen’s capabilities approach, a liberal society is committed to the equalization of capabilities that roughly correspond to one’s ability to lead a human life with reasonable longevity, nutrition, health, and social functionings. The upshot of Sen’s approach is also that we must seriously try to improve the conditions of the poor in this world.

The Character and Extent of Poverty

Poverty is not a single phenomenon with a simple foundation, invariant across geographic location and social condition. Poverty has many faces. Important aspects of the global poverty profile include its global distribution, the rural-urban divide, its gender aspect, and features specific to particular countries or regions such as the caste system in India.

The spatial nature of poverty

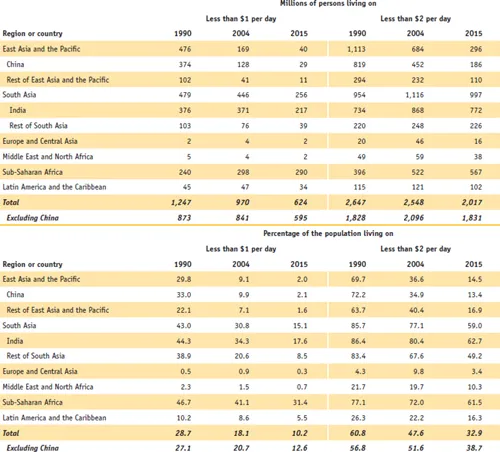

Using two standard measures of poverty, namely living on less than $1 or $2 per day, Table 1.1 shows World Bank data and forecasts across the economically less developed part of our world. South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have two of the largest concentrations of the poor. In the more than sixty years since the end of World War II, East Asia has undergone the greatest progress in reducing poverty. In the last thirty years, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has shown a remarkable reduction in poverty also, although in absolute numbers China still has a large number of poor people.

More specifically, approximately 1 billion people globally lived on less than $1 per day in 2004, and more than 2.5 billion or half of all those in low- and middle-income countries lived on less than $2 per day. Although there has been limited reduction in those numbers since 1990 (none at all at $2 per day), the percentages have declined significantly, and the World Bank anticipates substantial further decline by 2015. In fact, the Bank expects the percentage of those living on less than $1 per day to have been cut by almost two-thirds between 1990 and 2015. Clearly, the extremely rapid reduction of poverty in China greatly influences broader trends. In India the numbers of the poorest fell little in the 1990s, but Thailand and Vietnam (not shown) achieved significant reductions.1 And sub-Saharan Africa has experienced much smaller reductions since 1990 in the percentage living on less than $1 or $2 and, in fact, has seen substantial growth in the numbers of people living at those levels.

Table 1.1 World Bank data and forecasts of poverty

Source: World Bank 2008: 46 (Table 1.5).

In addition to region of the world, urban/rural location affects the likelihood of living in poverty. The UN calculated that the urban share of global population reached 50 percent in 2007. In developing countries, however, the portion of the population in urban areas is closer to 40 percent, with the 50 percent number to be reached in about 2020.2 Poverty is, however, disproportionately a rural phenomenon, and only about 30 percent of the world’s poor live in urban areas (Ravallion 2001b: 2). Poverty will likely become predominantly an urban phenomenon as urban population growth outpaces that in rural areas. Martin Ravallion forecast that the urban share of poverty will reach 40 percent in 2020 and 50 percent about 2035 (when the urban population share reaches 61 percent).

The social nature of poverty

Subpopulations within societies differ significantly in their poverty levels. Both case studies (Agarwal, Humphries and Robeyns 2005; Nussbaum and Glover 1995) and empirical analyses (UN ECLAC 2005: 44–45) indicate that being female makes one more vulnerable to poverty.

One of the distressing manifestations of poverty and gender inequality is the phenomenon of excess mortality and artificially lower survival rates of women in many parts of the world. This phenomenon is known as “missing women” (Sen 1992b). In the United States and Europe, there tend to be more women than men in the total population, with a female-male ratio of 1.05. One reason is that women are biologically “hardier” than men and, given equal care, survive better. The situations in the developed West and in less developed nations reveal a sharp contrast. The contrast is especially grim in parts of Asia and North Africa, where the female-male ratio can be as low as 0.95. Using the Western ratio as the benchmark, approximately 100 million women worldwide appear to be “missing.” Even adjusted measures with other benchmarks suggest that the number is roughly 60 million.3

The effects of income poverty and various dimensions of social exclusion upon the lives of individuals and subpopulations overlap and interact. A further element of vulnerability comes from being in the wrong segment of a status-hierarchical society. One example of this is the caste system in India. Particularly in rural areas, the intersection of gender and caste can make a woman very vulnerable, as the following example so movingly illustrates:

“I may die, but I still cannot go out. If there’s something in the house, we eat. Otherwise, we go to sleep.” So Metha Bai, a young widow with two young children in Rajasthan, India, described her plight as a member of a caste whose women are traditionally prohibited from working outside the home—even when, as here, survival itself is at issue. If she stays at home, she and her children may die shortly. If she attempts to go out, her in-laws will beat her and abuse her children (Nussbaum and Glover 1995: 1).

Like gender, age often shapes poverty rates, with the young and old suffering disproportionately. Ethnic differences within countries also commonly coincide with considerable differences in poverty levels. For instance, indigenous populations typically have rates of poverty that are multiples of the rates in European settler populations, as do the descendents of imported slaves. An extreme example is Paraguay, where the rate is nearly 8 to 1 (UN ECLAC 2005: 49).

This report will not be able to forecast poverty specifically for social subgroups, and its differentiation of poverty will be overwhelmingly structured by the borders of countries. Moreover, it will focus heavily upon the income bases of poverty. It is important, nonetheless, to recognize the complex social character of poverty around the world.

Why This Report?

The phenomenon of global poverty is the fundamental issue of global development, and a web search on “poverty” brings up over 50 million cyber addresses. One might therefore reasonably conclude that enough has been and is being done by others. Yet there are several remarkably large deficiencies in the huge body of studies and policy analyses on poverty. First, partly because of the time horizon of 2015 identified by the Millennium Development Goals, and in spite of the very long horizon of many interventions to reduce poverty, little analysis explores the longer-term human future on this critical issue. Second, global analyses of poverty typically do not cover regions of continents, much less individual countries. It is critical, however, to be able to explore the spatial dimension of poverty broadly. Third, there is a natural tendency for analysts and institutions to focus on specific, targeted interventions for several reasons: (1) sometimes because they are seen as “silver bullets”; (2) sometimes because of scholars’ knowledge of or familiarity with the research terrain; and, more fundamentally, (3) because it is critical that we understand the different implications of various interventions. A much smaller portion of analysis explores a wide range of interventions, however, both singly and in comparison and in combination.

The need for a long horizon

Poverty will not disappear by 2015, even when defined with a bar as low as an income of just $1 per day for each individual. If the MDG of reducing the rate of poverty in the developing world by half between 1990 and 2015 were met but not exceeded, there would still be nearly 890 million people living on less than that amount. And although there is substantial consensus that the goal will likely be met and even exceeded globally, it will almost certainly not be met in sub-Saharan Africa.

We thus need to think beyond 2015, as well as maintaining and strengthening our efforts through that year. As humans, we understandably tend to be impatient. We want to see change in our lifetime so that we and our families and communities can benefit from it. Yet much sociopolitical change is slow. Payoffs for investment often accrue to successor generations, sometimes the children of those who act, but often their grandchildren and even great-grandchildren. In addition, changes often require sequencing. Thus shorter-term and longer-term horizons are essential.

It is also important to understand that, as critical as the reduction of poverty may be, it is not the only high-priority human goal. When historians of the future look back on the twenty-first century, hopefully they will be able to look at it in terms of a long, broad sustainability transition. That transition is likely to be defined, much as it already is today, in terms of individual human development (including poverty reduction and the development and exercise of human capabilities), social development (including the expansion of human participation in governance and social decision making on the basis of justice and fairness), and a sustainable relationship between humanity and its broader environment. The positioning of poverty as one aspect of this larger transition is another reason that both longer-term and near-term perspectives are needed.

The importance of maintaining global and country-specific perspectives

The global assault on poverty requires simultaneous attention to multiple levels of analysis. Global and continental perspectives help us to grasp the magnitude of the problem, to understand trends, and to begin to speculate about the appropriate interventions. Although some action against poverty is clearly being undertaken at the global level, most of it remains at and within individual countries.

This study crosses levels of analysis. Earlier chapters devote more attention to the global and continental level. Chapter 7 begins to explore regions within continents, and Chapter 8 dives into s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- List of Boxes

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Concepts and Measurement

- 3 Drivers and Strategies for Poverty Reduction

- 4 Tools for Exploring the Future of Global Poverty

- 5 The IFs Base Case: A Foundation for Analysis

- 6 The Future of Poverty: Framing Uncertainty

- 7 Changing the Future of Poverty: Human Leverage

- 8 The Multiple Faces of Poverty and Its Future

- 9 Poverty in a Broader Context

- 10 The Future of Global Poverty and Human Development

- Appendix 1 Cross-Sectional and Lognormal Formulations for Poverty

- Appendix 2 Using Lognormal Income Distributions

- Appendix 3 Deep Drivers of Economic Growth and Distribution

- Appendix 4 Countries in UN Regions and Subregions

- Appendix 5 Points of Leverage in International Futures (IFs)

- Bibliography

- Forecast Tables: Introduction and Glossary

- Forecast Tables

- Index

- Author Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reducing Global Poverty by Barry B. Hughes,Mohammod T. Irfan,Haider Khan,Krishna B. Kumar,Dale S. Rothman,Jose Roberto Solorzano in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.