- 446 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Working Through Synthetic Worlds

About this book

Virtual environments (VE) are human-computer interfaces in which the computer creates a sensory-immersing environment that interactively responds to and is controlled by the behaviour of the user. Since these technologies will continue to become more reliable, more resolute and more affordable, it's important to consider the advantages that VEs may offer to support business processes. The term 'synthetic world' refers to a subset of VEs, having a large virtual landscape and a set of rules that govern the interactions among participants. Currently, the primary motivators for participation in these synthetic worlds appear to be fun and novelty. As the novelty wears off, synthetic worlds will need to demonstrate a favourable value proposition if they are to survive. In particular, non-game-oriented worlds will need to facilitate business processes to a degree that exceeds their substantial costs for development and maintenance. Working Through Synthetic Worlds explores a variety of different tasks that might benefit by being performed within a synthetic world. The editors use a distinctive format for the book, consisting of a set of chapters composed of three parts: ¢ a story or vignette that describes work conducted within a synthetic world based loosely on the question, 'what will work be like in the year 2025?', founded on the expert authors' expectations of plausible future technologies ¢ a scholarly review of the technologies described by the stories and the current theories related to those technologies ¢ a prescription for future research required to bridge the current state-of-the-art with the notional worlds described in the stories. The book will appeal to undergraduate and graduate students, professors, scientists and engineers, managers in high-tech industries and software developers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

An Essay on the Cognitive Benefits of Stories

A Story About Stories

A good friend of mine once told me that every good story should start with the words, “There I was…”

So, there I was, a young faculty member at the University of Montana who had through luck and slim virtue been offered the opportunity to ride aboard a Navy command ship, the USS Coronado. The Coronado was based out of San Diego, where it was the floating headquarters of the US Navy’s 3rd Fleet. I had been conducting a series of studies on decision making under time pressure; this activity had led to an invitation to ride the command ship during a simulated warfare exercise.

The exercise lasted two weeks, during which I was allowed to wander freely aboard the ship, attend the various meetings and briefings, interview the fleet staff, and otherwise make a nuisance of myself. I had a wonderful time, and frankly I don’t recall very much about it. But this one thing is firmly embedded in my memory: the evening meals.

For sailors, there isn’t much to do aboard ship except eat, sleep, and work. I noted that the officers and senior enlisted personnel that comprised the Fleet staff tended to sleep about 4 hours per night, minimize their time spent eating, and devote the remainder of each day to work. These men and women typically had the equivalent of two full-time jobs as well as some ancillary duties. So, they didn’t have a lot of time for eating. The exception was the evening meal.

Each evening, the commander of 3rd Fleet, VADM Herb Browne, would attend a formal dinner in the Flag Mess. The Navy is big on protocol; as a visiting professor, I was granted the courtesy of eating in the Flag Mess. On the first night, I showed up for dinner, and discovered that I was seated immediately to the admiral’s right. We made small talk during the meal, and when the dessert was served, the admiral leaned over to take a good look at my name badge, and then he asked me something like,

“What is an egghead from the University of Montana doing on my ship?”

I’m sure his actual words were more polite—but I got the gist. I responded in a properly sycophantic manner with,

“Well sir, I have been conducting research on decision making under time pressure. And I’m here to see how the experts do it.”

Everyone at the table, which included most of the senior staff, had been observing this exchange. The admiral swept his gaze around the table, and looked back to me, and said,

“Decision making under time pressure, eh? Let me tell you a story about the time I was captain of the John F. Kennedy. There I was, …”

And the admiral proceeded to tell us all a story about a particularly hair-raising incident from his earlier career during which he came very close to sinking a nuclear aircraft carrier and creating the world’s most heinous ecological disaster while sailing peacefully in the Red Sea. The admiral finished his story of near-disaster by acknowledging a variety of contributing factors to what was almost an example of really bad decision making under time pressure.

You see, admirals don’t get to be admirals by making mistakes. In the Navy, decisions are frequently judged by the quality of their outcomes rather than the quality of their process. During subsequent meals, I came to understand that the admiral’s story of near disaster was a form of organizational memory. The admiral used me as a foil to tell a story for the benefit of his junior officers. The point of the story was the self-criticism offered at the end, in which the admiral described a few things he might have done differently if he’d had the benefit of his current wisdom.

As I said, I don’t recall much about those two weeks on the USS Coronado. But I remember the admiral’s story almost word for word. This experience was an eye-opener for me. I resigned my tenure at the university, and was hired as a scientist for the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center—SPAWAR for short. During three years at SPAWAR, I had several additional opportunities to ride ships, and visit other shore-based command centers. I repeatedly witnessed storytelling by senior officers in those mealtime settings.

For example, on another cruise aboard the Coronado, I was seated next to Major General Charles Bolden, USMC. The general was wearing aviator’s wings; at some point I asked him if he was a fixed-wing pilot. Without missing a beat, the general acknowledged that he was a fixed-wing pilot, and proceeded to tell me some stories about his days at the Naval Test Pilot School in Paxtuxent River, Maryland. Again, the stories took the form of interesting events that were almost tragic. And although the general was talking directly to me, I know that I wasn’t the only one listening because the next day a young officer approached me and asked, “Did you know that General Bolden flew four Space Shuttle missions, and was the commander for two of them?” Fixed-wing pilot, indeed.

Over the years, I’ve written dozens of scholarly articles about decision making and computer-aided decision support. But, I think one of the most important observations that I’ve ever made is one about which I’ve never written: the role of stories as an aid to memory. In the essay that follows, I explain some of the reasons why stories are important as a method for conveying information. And hopefully, my own anecdotes will help the readers to remember that they can always pull this volume off their shelves when they need access to the details.

Research On Storytelling

Storytelling has been used as a form of communication since ancient times, beginning with chants to convey complex multi-layered stories (Greene 1996, Cooper and Simonds 2003). The first written record of a storytelling activity was found in an Egyptian papyrus called the Westcar papyrus, recorded sometime between 2000 and 1300 BCE (Greene 1996), where King Khufu heard tales told by his sons about the wonders of other days and the doings of magicians. Nietzke (1988) calls storytelling the “ancient new method” because they have been used for centuries and teachers are rediscovering the benefits that storytelling can have for learning.

Other terms that are synonymous with storytelling include narratives, stories, histories, fables, epic, and folktales (Gudmundsdottir 1995). These all refer to a basic structure that: 1) includes accounts of action usually involving humans or humanized animals; 2) develops characters in the story; 3) has a beginning, middle, and an end; and 4) contains parts held together by a plot. A number of taxonomies have been proposed to classify the near infinite varieties of stories (Polkinghorne 1988). For example, Schank (1990) describes four types of stories. Gergen and Gergen (1986) have devised a system with three categories. Frye’s (1957) story taxonomy includes 5 categories: myth, romance, high mimetic, low mimetic, and ironic.

There are a couple of important points to make about these schemes. First, the fact that scholars can’t agree on a single taxonomy hints that none of these are universal for all humans across all contexts. So, the categories might be dependent on factors related to personal experiences such as culture or professional training. But, second, the consistent attempt by scholars to identify categories suggests that such categories do exist, and may be nearly universal within their target population. That is, humans in broad categories may have been exposed to certain types of stories so often that they have become able to recognize and anticipate the story elements. That is certainly the case in the military, with respect to the near-disaster story format. Aircraft pilots tell similar stories; they call it hangar-flying. Hunters and fishermen talk about, “the one that got away.”

These classifications help organize the stories either in published or oral forms. We, as human beings, seem to have an instinctive desire to share our feelings and experiences (Greene 1996, Polkinghorne 1988, Schank and Abelson 1995). We tell stories in order to make sense of our world; we listen to other people’s stories in order to understand them. Everyone has a story. Some researchers (e.g., Schank and Abelson 1995) postulate that virtually all human knowledge is based on stories. Stories have the power to capture and hold attention (Raines and Isbell 1994). Detailed information can be recalled from a story because individuals can internalize and identify with the story (Polkinghorne 1988).

Because storytelling is all encompassing in everyday lives, it’s not surprising to find applications of storytelling techniques in various settings. For example, the court systems utilize storytelling in criminal trials to process vast amounts of information and to make complicated judgments based on governing rules (Pennington and Hastie 1995, Bennett 1997). Organizations draw on storytelling to communicate corporate cultures and transfer knowledge in the workplace (e.g., Swap, Leonard, Shields, and Abrams 2004,

Snowden 2004). Consumer marketing uses storytelling to enhance brand connection to a product (Escalas 2004). In career development, storytelling has been used to help reshape career goals (Riendeau 2004). The counseling professions use storytelling in trauma recovery (e.g., Leseho 2005), grief and bereavement process (e.g., Bosticco 2005), anger-management (e.g., Leseho and Marshall 1999) and in coping skill development of juveniles (e.g., Haggerty 2005). Medical professionals affirm the healing power of story and storytelling (McCaleb 2003, Coles 1990, May 1991). The ubiquitous use of storytelling shows its collective appeal to the workings of the human mind.

Despite its universal appeal, stories or narratives have only recently been examined in the cognitive sciences (Polkinghorne 1988, Jonassen and Hernandez-Serrano 2002). The terminology “narrative intelligence”, born out of work in AI, describes how narratives intersect with intelligence (Mateas and Sengers 2006). It stresses the importance of narratives in sense making. Schank and Abelson (1995), early proponents of the importance of storytelling in human cognition, believe that it is more important to study the cognitive and social nature of storytelling than to pursue abstract, formal and compartmentalized domains of human information processing. They believe “stories about one’s experiences and the experiences of others are the fundamental constituents of human memory, knowledge and social communication.” (p. 1). Virtually all human memory is based on stories built around past experiences. What we know, learn, and understand is structured in stories. Human memory is a collection of thousands of stories we remember through experience; stories we remember because we heard them or stories we remember because we composed them. Our knowing is based on stories.

Cognition and Storytelling

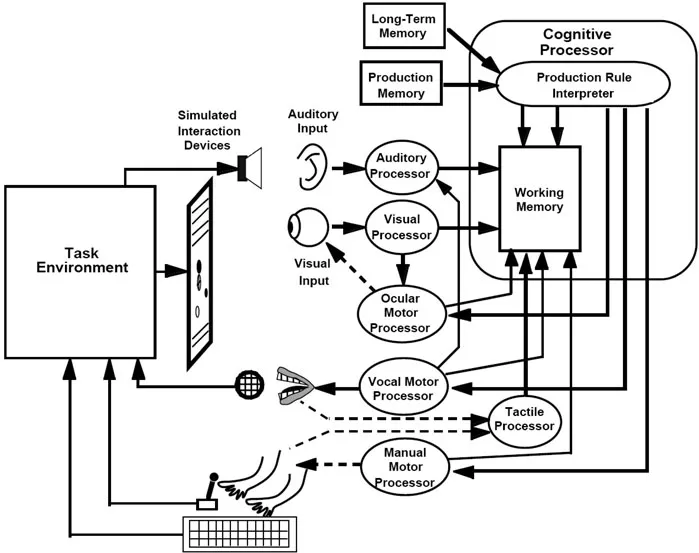

Research in memory and learning has substantially improved our understanding of human information processing. Such research has generated a variety of theories and models describing how people process information. The capacity or resource models (e.g., Kahneman 1973, Navon and Gopher 1979, Wickens and Liu 1988) view the human system as having a limited reservoir of resources that are quantifiable, divisible, allocatable, and scarce. Multiple resource theory proposes that there are separate and finite reservoirs of cognitive resource (Wickens 1984; 2002), some of which are potentially available simultaneously for different purposes. There have been several attempts to characterize the interactions among our cognitive processes (e.g., Card, Moran, and Newell 1983). One such model that has become widely uses is the EPIC model (Kieras and Meyer 1997, Figure 1.1). The model shows various cognitive resources, including different types of memory (long-term and separate working memory stores for visual and auditory working memory), separate processors for perception, motor control, and an executive “cognitive” processor. Working memory refers to temporary or “short-term” memory that humans use to buffer our recent perceptions, or to gather our recollections from “long-term” memory.

Figure 1.1 EPIC Model of Memory (from Kieras and Meyer 1997)

It requires some cognitive effort to retrieve memories from long-term storage. Once those long-term memories are “active” in short-term memory, it also takes some ongoing effort to keep them active. These efforts are expended by the cognitive processor, and are generally referred to as “attention.” Humans have a finite amount of attention resource, which can be consciously directed to a variety of tasks, such as retrieving memories from long-term storage, maintaining memories in short-term storage, directing sensory activities (e.g., looking or listening carefully), and controlling motor processes. We have difficulty dividing attention among several tasks, or attending to all the information provided by the senses (Broadbent 1958, Treisman 1969). As a result, we often do not perceive most of the information that is available to us (Lavie 1995). As Nobel Laureate Herb Simon has said, “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.” (Varian 1995). In the following paragraphs, I offer an explanation why stories have the potential to mitigate the limitations of our cognitive resources.

The presence of separate short-term memory stores has received significant recent support (Baddeley 1992; 1998, Baddeley, Chincotta, Adlam 2001, Wickens 2002, Wickens and Liu 1988). Baddeley’s terminology has been generally adopted as the standard; he refers to these separate resources as “visuo-spatial” and “articulatory-loop” memory. While Chase and Simon (1973a; 1973b) adopted Miller’s (1956) estimate for the size of each short-term memory store as about 7 ± 2 items, more recently, the size of the visuo-spatial store has been estimated as a maximum of 4 items (Zhang and Simon 1985, Gobet and Clarkson 2004, Gobet and Simon 2000). These limitations are additive; it is possible to simultaneously hold about 4 items in visuo-spatial...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter 1 An Essay on the Cognitive Benefits of Stories

- FORECASTING

- FORENSIC ANALYSIS

- COGNITIVE AMPLIFIERS

- TRAINING

- INFRASTRUCTURE

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Working Through Synthetic Worlds by Kenneth W. Kisiel, C.A.P. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Computer Science & Human-Computer Interaction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.