![]()

Part 1

Theoretical Features

![]()

1

Development of Cognitive Analytic Therapy

Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) is a brief, integrative model of psychotherapy originally created and delivered in the health service in the United Kingdom. CAT was developed during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s by Dr Anthony Ryle. Ryle was originally a GP and so brought a medical perspective to his work. He moved from this role to working as the director of the University of Sussex Health Service before becoming appointed in 1980 as a consultant psychotherapist at St Thomas’s Hospital in London. He had a desire to develop a compassionate understanding of a person’s difficulties and to do this collaboratively, using a shared language that his clients could understand. Ryle was, at this time, also concerned with access to therapy and equity of provision within the NHS and was working with a particularly complex and socially and economically disadvantaged group of clients within Inner London. He developed CAT in response to these needs, creating a therapeutic approach that was time limited and focused on empowering clients to develop understanding and skills that they could take forward and use in their lives beyond therapy.

During the 1970s Ryle wrote a series of papers based on research projects he had undertaken, exploring why people do not revise dysfunctional patterns of behaviour, feeling and thinking (Ryle, 1975). He also researched and wrote papers in which he described his focus on relationships in his clients’ lives (Ryle, 1985). He documented concepts for describing beliefs, emotions and actions that people repeat in their interactions with themselves, the world and others. Ryle noted parallels between his clients’ relationships with others and their internal working relationship with themselves. Through this research, Ryle aimed to create an integrated model which took the most effective elements from other models, including psychodynamic therapy, personal construct theory and cognitive psychology.

By integrating Kelly’s personal construct theory (Kelly, 1955) with object relations theories (Ogden, 1983), Ryle was able to bring the analytic tradition into a model that would allow for joint understanding and shared language to develop with the client whilst retaining a focus on the important processes of transference and countertransference.

Ryle’s ideas were taken forward during the 1980s by a group of colleagues who shared a similar passion. They integrated further ideas of dialogism (the social and psychological context to our communications) and Vygotsky’s activity theory (the theory of the social context of development) (Ryle, 1991). The result was a theory of how we as people are, and how we move through our lives responding to the various challenges this inevitably brings, as opposed to simply a theory aimed at explaining disorder. What followed was the development of a new and exciting training programme which led to the beginnings of the training in CAT that exist today.

The integration of these ideas led to the concepts that are central to the CAT model: that we are social beings and that often at the heart of mental distress is a difficultly in how we are relating to ourselves and others. The emphasis on how our internalised early relationships shape our adult behaviour allows for an empathic understanding of a person’s presentation. The therapeutic relationship becomes a major ‘vehicle for change’ within therapy as observations are made of the repeating relating patterns that the client brings and new ways of relating are tried out. Such understandings are shared with the client using diagrammatic reformulations (a map) and prose reformulation (a letter).

In its origins, CAT was designed to help those clients who were complex and difficult to treat and CAT retains such a place today within the NHS, often as an ‘end of the line’ approach. CAT evolved initially as a brief (16-session) therapy and can be extended for working with those with more complex presentations such as personality disorders or eating disorders. Although originally developed as a model for individual therapy CAT has also been further developed to use in therapy groups or in teams. As explored in Chapter 29, using CAT in indirect work can be a way of helping other professionals in their work when direct therapeutic work is not possible or as a supplement to therapy.

Whilst the model was first designed and used within adult mental health settings, the approach has grown over the years and there is increasing evidence for its usefulness across a variety of client groups and settings, as discussed in Chapter 27. The CAT model is continuing to demonstrate its usefulness in various applications and settings and in different formats, making it an essential model for effective work within the modern-day NHS.

![]()

2

Development of reciprocal roles

Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) is an integrative model of therapy which, as its name suggests, draws upon aspects of both cognitive and psychoanalytic theories. At its centre is its assertion of the importance of early life experiences and the roles and strategies we develop in response to these. As such it is a theory of how we are as people, rather than a theory of specific disorders or problems.

Within CAT early experiences are seen as central to how we learn about ourselves and others. From these experiences, templates are formed of our early relationships that are taken into adult life and used as templates for future relationships. These are used to predict others’ behaviours and responses, as well as influencing how an individual relates to themselves. In CAT these templates are called reciprocal roles (RRs).

When considering the development of RRs it can be useful to reflect on the interaction that may be seen between a young infant and its caregiver during a simple task such as bath time. What would we see during this interaction? What would the parent be doing, and how might we observe the infant respond in relation to this? We are likely to observe the caring nature of the interaction: of seeing the parent gently talk to and play with the infant, of eye contact, the parent explaining what they are doing, even though the infant can’t understand verbally what is being said. We will also see how the parent prepares the infant for the bath, gently undressing her, and the infant’s anticipation of this as she recognises predictable cues, which may bring happy squeals of excitement. What we see in this interaction is an illustration of a secure attachment relationship that will shape the development of an RR; of a parent modelling attuned, compassionate and predictable care; and the infant having the experience of receiving care and compassion in a kind and predictable way (Stern, 1985).

This interaction, if it occurs repeatedly and consistently, will be internalised by the infant in the form of an RR (Ryle, 1985). This comprises two linked components which include the parentally derived experience (what the parent does to the child) as well as the child-derived experience (how the child experiences this). So in the previous example the RR would be one of caring (parentally derived role) to cared for (what is experienced by the child). Within CAT it is proposed that these roles are played out intrapersonally in how we relate to ourselves and interpersonally within our relationships with others, thus determining future relationship patterns.

As the infant develops the ability to communicate verbally, more sophisticated social behaviour may emerge. Young children may often be seen replicating events that they themselves have experienced; dressing or bathing their dolls or cuddly toys, taking them for walks in their buggies, or reading to them. Older children may be observed re-enacting events from school: playing teachers, lining up their toys or younger siblings on the sofa whilst taking the register, and taking on the rather stern teacher’s voice. This is illustrated further in Silver’s (2013) observational studies of play in children, in which children play ‘making tea and cake’ and share this with the other children around them. Those children who have learnt these behaviours from their own interactions at home know how to respond, politely taking the tea and demonstrating learnt social skills of offering thanks and positive comments. In contrast children from families where this learning has not taken place will instead re-enact the behaviours observed in their own home, resulting in a different type of interaction. What we see in these behaviours is the early re-enactment of RRs.

Not all are fortunate to receive healthy nurturing experiences, and many clients may have been subject to a critical, abusing or neglecting environment. In the same way as positive nurturing experiences, these relationships are also internalised and influence how the child acts and responds in other relationships. Consider, for example, the situation of a parent helping a child to learn to ride a bike. What we may see in this interaction is the parent running alongside, holding onto the bike, and then letting go, allowing the child to take those first few metres alone. The child may pedal a short distance but then wobble and fall. If she is lucky she will receive praise and encouragement. “Well done! Look how far you went! Let’s get you up and have another go!” In response the child is likely to get up excitedly and want to try again. However, imagine a different response from the parent: “Why did you stop pedalling? You should have kept going! You’ll never learn to ride a bike if you keep doing that, we may as well go home now!” Such an experience, if it occurs repeatedly, is likely to lead to the internalisation of a very different RR, and may result in the child feeling upset, useless and wanting to give up.

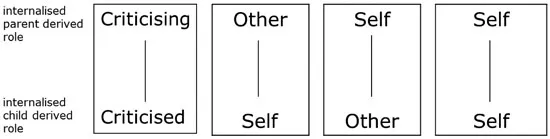

The previous examples illustrate the central concept of RRs: that as children we learn from what we experience and internalise the interactional patterns of our early relationships. This is beautifully illustrated in the poem ‘Children Learn What They Live’ by Dorothy Law Nolte (1972). These RRs are then re-enacted in future relationships, both with ourselves and others. Therefore those who have had a predominant experience of the world and others of being OK will internalise a sense of the world and others as being safe and secure. In CAT this experience is internalised as an RR of caring to cared for and will influence patterns of relating to self and others. RRs may be re-enacted in three different ways as outlined in the following list and illustrated in Figure 2.1:

- Other to self: the adult will expect others to take the parentally derived role in relation to herself

- Self to other: the adult will adopt the parentally derived role in relation to others

- Self to self: the adult will take the parentally derived role in relation to herself

This means that a child shown kindness and care will come to anticipate and be open to experiencing kindness from others (other to self) as well as be able to show kindness to herself (self to self) and other people (self to others). In contrast, a child who experiences others as critical or rejecting will expect criticism or rejection from others (other to self), behave in this way towards themselves (self to self) and may also relate to others in a critical or rejecting way (self to others) (Ryle, 1985).

Figure 2.1 Reciprocal role illustration of self to self, self to other and other to self

The range of RRs will be dependent on an individual’s experiences, but are likely to be associated with repeated persistent patterns in key relationships and/or significant traumatic experiences. However, from clinical experience some broad categories may be observed which are associated with common themes, as outlined in Table 2.1. In addition to RRs that develop in direct response to a child’s experiences of care, compensatory, idealised roles may develop from a sense of what is missing or observed; for example an idealised role may develop in response to an absent caregiver, such as in the case of divorce or bereavement (“if only my mother were here, then …”), or from observation of a charismatic parent who receives admiration from others. Alongside these more problematic RRs may be healthy RRs that may have developed from positive relationships with other caregivers, such as a trusted relative, teacher or friend. The presence of these can act as a healthy island (McCormick, 2008, p. 35) and buffer and lessen the impact of problematic roles.

The challenge in therapy is when there is a limited range of roles available and the absence of healthy roles to draw upon, as is often seen in individuals who have experienced severe trauma and neglect and who may have difficulties associated with personality disorder. In these situations, the therapist is likely to be readily invited into these RRs; for example, being experienced either in an idealised, perfectly caring role or a rejecting, abandoning role, with little sense of middle ground or transition between these. Within therapy the aim is to develop awareness and understanding of the full RR repertoire, strengthen and facilitate the development of healthy roles, and enable the individual to draw upon a range of roles with flexibility and a lack of critical judgement.

| Childhood experience | Reciprocal role |

| Physical, emotional or sexual abuse Bullying | Abusing – abused Attacking – attacked |

| A carer who is critical or for whom nothing is ever right or good enough Conditional approval or acceptance | Criticising – criticised Judging – judged Disapproving – disapproved Contemptuous – contemptible |

| Absent Neglecting Too busy | Abandoning – abandoned Neglecting – neglected Rejecting – rejected Overlooking – overlooked Invalidating – invalidated |

| Idealised (fantasy) roles, often associated with an absent or distant parent | Perfectly caring – perfectly cared for Rescuing – rescued Admiring – admired |

Table 2.1 Examples of reciprocal roles

![]()

3

Development of survival strategies

Central to the Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT) model is the basic premise that we are not born acting or responding to situations in a particular way, but that how we react to others and the world around us is shaped by our early experiences and environment. These experiences, along with our biological disposition and inherited temperament, combine to make up who we are as individuals and our typical ways of thinking, responding and relating to others and ourselves. As we have seen, in CAT, early relational experiences are seen as important, and are internalised in the form of internal cognitive structures which are named reciprocal roles (RRs) (Ryle, 1975).

As human beings we have essential needs in order to survive and develop into healthy adults. These include the need for physical and emotional care, and evidence from neuroscience shows us that both are of central importance for healthy development (Gerhardt, 2004). A helpful way of thinking of this is in terms of the development of a seed. Given optimal conditions, seeds have the capacity to grow into healthy plants. However, in order to achieve this, a set of conditions must be met. This may include the need for temperature, light, water and nutrients. Not only this, each of these needs must be met at the right time. For example, some plants may need moisture and darkness in order for germination to occur, whereas others may need light and warmth. Not having the optimal conditions doesn’t mean that the seed will not germinate and grow, but how it grows will be influenced and shaped by its early environment. For example, without the ideal level of light, moisture or temperature it may grow tall and spindly, or weak and fragile.

In a similar way, as human beings we have needs that must be met to ensure healthy development. As well as basic physical needs for food, water and an optimal environment, as mammals we also have a need for emotional nurturing and care which is essential from an evolutionary perspective to ensure survival (Gilbert, 2009). A healthy attachment relationship between an infant and a responsive and caring other has been shown to be important to the development of healthy emotional and social behaviour (Bowlby, 1969; Ainsworth, 1973). Research such as that carried out by Harlow in the 1950s illustrates the importance of emotional care, as demonstrated by the finding that infant monkeys need physical comfort as well as food in order to thrive (Harlow and Zimmermann, 1958). This is supported further by studies into human infants, which show that emotionally deprived environments can impact negat...