![]() PART 1 Enterprise Risk Management and Corporate Governance

PART 1 Enterprise Risk Management and Corporate Governance![]()

CHAPTER 1 Risk Management and Governance in Context

Corporate Governance

In a superficial sense, corporate governance is something of a fancy term for good corporate management. However, the term ‘good management’ perhaps lacks the gravitas and locus of accountability implied by ‘corporate governance’, which is very much the primary responsibility of the board of directors. Corporate governance refers to the system by which companies and other organizations are directed and controlled (FRC 2010).

A board’s governance responsibility encompasses the expression of corporate values; setting the desired tone and attitude; issuing policies, strategies, control standards and criteria for accountability, transparency, probity and risk; monitoring and reviewing performance; and demonstrating leadership with a clear focus on sustainable success.

Ultimately, corporate governance is all about ensuring that the interests of shareholders and other stakeholders (for example, employees, customers, the public) are protected. Without an effective risk management system, it is self-evident that no board could ever claim convincingly that the organization is under good governance. Boards should take a comprehensive approach to what ‘all significant risks’ means. Governance therefore requires that all significant risks to the business should be identified, analyzed and managed appropriately, whether by elimination, avoidance, reduction, control or other means (Waring 2001a). Although differing in emphasis and some aspects of principle and practice, this is the thrust of the original and revised Turnbull code in the UK (London Stock Exchange 1998, Turnbull 1999, FRC 2005), as well as other national codes, for example PRCCCG (2002), HKCCG (2005) and SCCG (2005) and generic international guides such as ISO 31000 (ISO 2009).

Corporate Risk Exposures

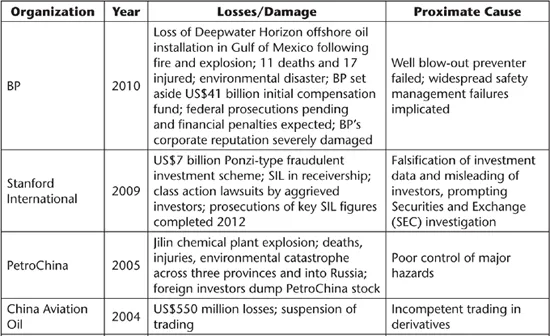

The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) annual Global Risks Report for 2011 (WEF 2011) emphasizes that business leaders and decision-makers need to switch to longer-term thinking for mitigating increasingly complex and interlinked global risks. Organizations are exposed to multiple and often complex and interacting areas of risk, including mergers and acquisitions (M&As), treasury risks, credit risk, integrity risks, security, marketing, product liability, contracts, capital projects, health and safety, major hazards, environment and many more. Above all these, two over-riding and critical issues are corporate reputation and brand, both of which take years to build up and perhaps only hours or days to destroy. Share values, market confidence and willingness of other companies to engage with yours all depend on reputation and brand and ultimately the very survival of the organization can be put at risk. Examples include:

Table 1.1 Some high-profile examples of business risk failures

China in particular is vulnerable worldwide to the fall-out from highly publicized cases of corporate fraud, environmental disasters and safety disasters in its industries (Waring 2005), such as Jilin/PetroChina and coal mines. Officially, well over 120,000 people are killed and over 600,000 handicapped in workplace accidents in China every year but the real figures are likely to be higher owing to under-reporting. In 2004, the official cost to China of its workplace accidents was 2 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) (Wang 2005). China has achieved a momentous industrial expansion and has secured inward investment from numerous Western corporations who have set up factories in China while others queue up to buy Chinese-made goods. These same companies are now nervous about ensuring that safety standards in their Chinese factories are as good as those back home. No Western CEO wants a public scandal with criticism in the media (for example, see cases 13.1 to 13.4 in Chapter 13) and major shareholders demanding his or her resignation for damaging the company’s reputation and share values.

The Global Marketplace

Today, we all operate in a global marketplace and have to think and act in a way that reflects the demands of the marketplace. Those demands now include a clear demonstration that the organization in all aspects of the undertaking meets the requirements of good corporate governance, including sustainability, corporate social responsibility and risk management. Many large companies in Asia, the Middle East and South America now want to be seen as global players and establish strong business relationships with the West: how will they be accepted if they ignore or pay only lip service to corporate governance as understood in the global context, including risk management standards? A poor risk management record will damage the mutual trust and confidence upon which inward investment and trade depend.

Equally, many enterprises in Asia, the Middle East and South America are now buying companies abroad and entering into joint ventures (JVs) and capital projects overseas. They will therefore need to undertake risk evaluations of the other parties and the contexts in which they will be operating. Such pre-contract ‘due diligence’ audits, which are relatively familiar to Western multi-national companies (MNCs) (see Chapter 8), are quite novel in Asia and the Middle East. Such audits need to cover not only the obvious areas such as finances/accounts and legal/contracts but also environment (who wants to discover too late that they have acquired major contamination legacies with horrendous clean-up costs?), human resources (HR) (who wants to discover too late that the corporate cultures do not match and they have entered a ‘marriage made in hell’?) and political threats (who wants to waste time and money pursuing a foreign asset whose acquisition is likely to be blocked by their government?). For example, the attempted US$18.4 billion purchase of Unocal by China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) in 2005 and the US$6.8 billion takeover of six US Ports by Dubai Ports in 2006 were thwarted by objections in the US Congress.

The Problems of Growth

The so-called BRICS Group (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) have shown higher economic growth rates in recent years than most developed countries. China’s economy, for example, has grown on average 10–12 per cent per annum for the past decade and only in 2010 began to show signs of a modest fall in growth rate. The benefits of growth are self-evident in China’s rapid modernization, its rising standard of living and consumer culture. However, the rapid economic growth which has been on the back of phenomenal industrial expansion has also brought problems (Barton et al. 2004), for example:

• few planning controls, leading to major hazards sites located in urban centres (for example, PetroChina/Jilin);

• poor process and waste controls, leading to major environmental damage (for example, Pearl River Delta);

• poor health and safety management, leading to many accidents, injuries and occupational ill-heath (Wang 2005);

• potential over-heating of the economy;

• raw material and energy deficits;

• the temptations of fraud and corruption;

• magnification of urban–rural gaps in economic and social benefits, leading to social tensions and unrest.

Steps have been or are being taken by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Government to address some of these issues (for example, SOASAC 2006, Yuanyuan 2004) but a lot remains for individual enterprises, whether State Owned Enterprise (SOE) or private, to do their part in prevention, control and general risk management. There remains a huge gap between the fine words of state regulations and codes on risk management topics and what actually gets implemented. There is, as yet, very little evidence that Chinese corporations are engaging seriously with corporate governance and risk management principles as outlined in this book (see Waring 2006b and c). Without such engagement and ongoing commitment and programmes, the disparity in standards between Chinese companies and the expectations of their overseas investors and customers is likely to cause them increasing problems with inward investment, their external operations and overseas markets. A similar picture emerges for companies in other Asian countries, the Middle East and elsewhere. The US$multi-billion so-called ‘Rajagate’ fraud and corruption case involving several mobile telephone companies in the Indian telecoms industry and a former government minister is just one example (see case 9.3 in Chapter 9). As recent World Economic Forum Global Risks Reports (WEF 2011, 2012) observe, economic disparity and global governance failures are exacerbating and driving a range of other risks, especially illicit trade, crime, corruption and state fragility. Economic imbalances contain the seeds for future financial crises.

The Purpose of Risk Management

As the Institute of Risk Management Guide to Enterprise Risk Management and ISO 31000 states (IRM 2010), a successful ERM initiative can affect the likelihood and consequences of risk materializing, as well as deliver benefits related to better informed strategic decisions, successful delivery of change and increased operational efficiency. Other benefits include reduced cost of capital, more accurate financial reporting, competitive advantage, improved image and perception of the organization, brand enhancement and, in the case of the public sector, enhanced political and community support.

Risk management provides a means to cope with a multiplicity of different kinds of risk and risk exposure so as to enhance beneficial outcomes and reduce harm and detriment. Risk management seeks where possible to reduce the uncertainty over how big an impact the risk would have if it materialized and how likely it is that the risk would materialize. However, there are two distinct types of risk exposure likely to affect an organization. The first type of risks are the so-called ‘upside risks’ which the author prefers to call speculative/opportunity risks, for example marketing, cash flow, product innovation, M&As, JVs, business investment. With these, the aim and expectation is to maximize beneficial outcomes and minimize detrimental ones. In reality, both beneficial and detrimental effects often occur in tandem and the art of effective risk management is to ensure that the balance is always heavily in favour of beneficial outcomes. The other type of risks is the set of pure risks, where success is determined by nothing bad occurring, for example health and safety, environment, fire prevention, security and information technology (IT) reliability.

In the author’s experience, there is a tendency for many directors and executives to believe that they should concentrate on speculative/opportunity risks, as these represent ‘normal management’ whereas pure risks such as health and safety, fire, security and other technical risks are ‘nuisance’ issues to do with tedious compliance requirements imposed from outside. This somewhat bizarre attitude is usually based on their often limited personal experience rather than any tutored knowledge of risk and its management. Associated with this line of thinking is the equally bizarre belief that pure risks are typically ‘operational’ and therefore less important and not a matter for the board. This demonstrates a confused understanding of what ‘strategic’ means, that is, to such individuals, strategic matters are of high importance and for the board’s purview whereas operational matters are far less important and should be kept away from the board. Of course, on the contrary (Waring and Tunstall 2005), the world is awash with examples of apparently workaday operational risks that, owing to poor risk management, suddenly became huge strategic risks for the organization (for example, the BP Deepwater Horizon case). A board should always know which operational risk exposures it needs to keep a close eye on and which it can safely delegate to executive management. See Chapters 3 and 4 for further discussion.

Corporate Culture, Risk Appetite and Risk Aversion

According to Turnbull (1999) and FRC (2005), the sound system of internal controls required for good governance ‘should be embedded in the operations of the company and form part of its culture’. Organizational culture is a complex subject that can only be touched upon within the scope of this book. Briefly, organizational culture may be regarded as: a set of unwritten, and usually unobtrusive, attitudes, beliefs, values, rules of behaviour, ideologies, habitual responses, language expression, rituals, quirks and other features which characterize a particular organization. For deeper insight into organizational culture in relation to risk see Douglas (1992), Turner (1992, 1994), Glendon et al. (2006), Waring and Glendon (1998) and Waring (2001b).

A survey of 1,419 business executives conducted jointly by Zurich Insurance and Harvard Business Review Analytic Services in 2011 found that, although the importance of risk management had risen in organizations since 2008, companies still have a long way to go in building an effective, risk-aware culture. Although two-thirds of respondents agreed that the importance of risk management had increased in their organizations, only 10 per cent reported that their executive management was ‘highly effective’ in creating a strong risk management culture. The implication is that senior managements are having difficulty with risk management implementation. This finding echoes the author’s experience over the past decade. The increasing attention by regulators, investors, the public and the media on risk issues, coupled with external reporting and scrutiny, inevitably has pushed risk management up the managerial agenda. However, despite what may seem a non-controversial subject having obvious benefits, as noted above many directors and executives still regard risk management as something rather alien and unwelcome, an imposed nuisance that ‘gets in the way of’ what they see as normal management. Such an attitude makes many reluctant to do much more than soft-peddle on risk management. See Chapters 3 and 4 for further discussion.

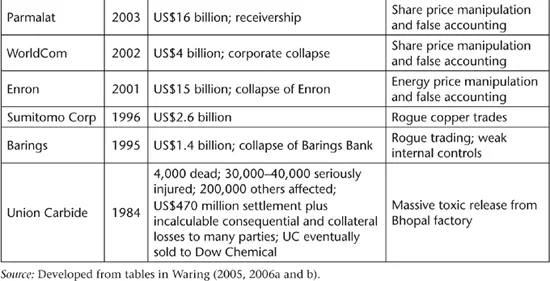

One test of the strength of an organization’s culture is to compare, on the one hand, risk management objectives that either the organization and/or professional advisers consider to be desirable with, on the other hand, the actual level of achievement against these objectives. Table 1.2 summarizes what in the author’s experience is found typically in many large organizations anywhere in the world but those organizations operating under corporate governance requirements and adopting ERM principles tend to reach the desirable objectives more quickly and with more lasting results.

Table 1.2 Disparities between some desirable risk management objectives and typical level of achievement

The board’s appetite (or propensity) for speculative or opportunity risks needs to be properly recognized and understood. It represents the motivational engine for growth and success. However, as the Institute of Risk Management Guidance Paper on Risk Appetite and Tolerance notes (IRM 2010), different functions and locations lower down in the organization are also likely to have different risk appetites and it will be important for the board to get these aligned and in harmony with those of the board so as to avoid potential distortions to the company’s risk profile and the creation of unwelcome exposures.

Responsible risk-taking requires that speculative or opportunity risks should be taken in an informed way and with adequate risk controls, so as to counter a reckless gambling or cavalier approach. Equally, there should be a healthy aversion to any pure risks that lack adequate risk controls.

The next 10–15 years will test the ability of many organizations to change from a culture of complacency and minimal compliance with a narrow set of risk-related regulations to one of a culture of responsible risk-taking that seeks to protect all the stakeholders’ interests and addresses the full array of risk exposures enterprise-wide. The development of such a mind-set requires strong leadership and a demonstration by the board and senior management that enterprise risk exposures have to be managed competently and effectively.

Risk Management Frameworks and Standards

Over recent years, a range of risk management frameworks and standards has been published and applied widely in businesses and other organizations. For several years, the Australian and New Zealand standard ASNZ 4360 proved very popular around the world as a useful guide to ERM. Other frameworks and standards have found favour in particular countries or with particular sectors or disciplines, for example Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX 2002) and COSO (2004) (the US and accountants), Basel II (2004) (banking and finance sector), DEFSTAN 56 (the UK defence sector and project managers). All of these have strengths and weaknesses but all share in their various ways a common thrust of requiring the assessment of significant risks and the implementation of suitable risk responses. This requirement is now expressed in the international standard ISO 31000: 2009 which applies to all kinds of organization regardless of sector. The overall risk management process expounded by ISO 31000 has the following essential components:

• Establishing the Risk Context (both internal and external).

• Risk Assessment (identification, analysis, evaluation and prioritization of risks, reference to board’s risk appetite, tolerance and acceptability positions; reference to legislation and standards both internal and external).

• Assessment-Based Risk Treatment (appropriate combination of control/mitigation options including cessation, avoidance, deferment, reduction, sharing, transfer and risk financing).

• Mo...