![]()

1

The Necessity of Feeling “Out of Place”

New York—Seoul—New York (1978–1992)

Section 1: Half-Siblings

Pic. 1.1 Before my siblings arrived in New York (from left to right: me, my mother, and my father (1980))

My parents immigrated to the United States in 1977 during the third wave of Korean migration to the US that began in 1965.1 I was born the year after in 1978 in New York as the only child to my parents. When I was six, my half-siblings, who were ten, six and four years older than me (born to a different mother), arrived from Korea to our home in New York. Before then the use of Korean, which I learned at home by speaking to my parents, was, according to my mother, predominantly for requesting things I wanted—food, toys, attention and so on, which my mother would give me unhesitatingly to prevent me from having tantrums. With the arrival of my half-siblings and to sustain a family of six, my parents both worked throughout the day and I was looked after by my half-siblings. I quickly learned that my tantrums didn’t have the same effect on them as they did on my parents. Getting what I wanted or, more importantly, being provided with things that I needed, such as meals, would require me to ask them nicely in Korean. I was anything but nice to them, however, because I resented having to ask in the first place when it was “my” house.

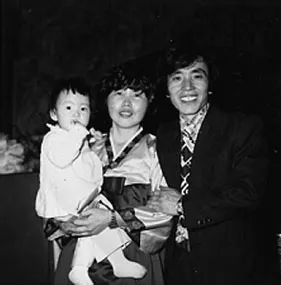

Such feelings of ownership are clearly reflected in certain artifacts from my past, as, for example, in pic. 1.2 where I state, “This is my home and my remote control and my parents and my country!!!!!!!! … my house … I want them to go back to their country!” They become “them” and Korea becomes “their country”—not mine. (Note: this template is also a part of another artifact in Chapter 4, pic. 4.2.)

Pic. 1.2 Template for writing diaries handed out in school during 4th grade. New York (1987)

Transcript:

I was watching tv and stupid dorko #1 stole the remote control! This is my home and my remote control and my parents and my country!!!!!!!! I threw the remote control and it landed on his head! OOPS! But that was an accident!! I swear!

Cut out their photos because this is my house! Puhahahahaha! [Note on picture of my brother: This is stupid dork #1]

Stupid dorko #2 and #3 [my two sisters] then came and blamed me for everything. HATE them all! I want them to go back to their country! They make me feel like the ugly duckling. 3 against 1! I’ll run away and never come back and then you’ll all be sorry!!

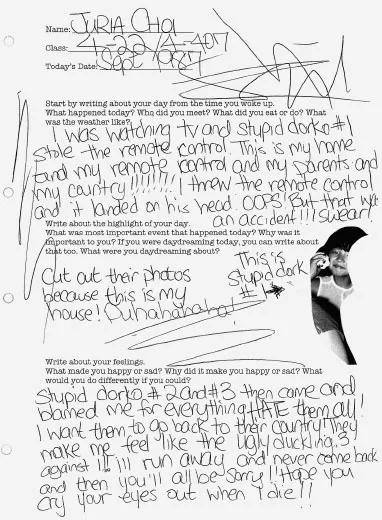

I saw myself as a member of the dominant society (as American), but the home was becoming a place where Koreans were the dominant group. Even to win a verbal battle, I needed to win it in Korean, which was impossible for me. I can only speculate now that cutting out everything else in pic. 1.3 might have been my way of seeing my parents and me as the “legitimate family.”

Pic. 1.3 Pictures of only mom, dad and me. Notice the cut out [see circled] of my brother’s face behind me. The missing part is the picture in pic. 1.2. New York (1987)

In looking more carefully at these silent acts of cutting, removing and self-writing, which Lemke (1995) might call having an “inner dialogue” (p. 89), what strikes me most is my sense of perceiving English as a form of power. It is not only that English was the only language I could fluently write, but in it, I could “talk back” (in this case, “write back”). Here, we need to take into consideration a nine-year-old child, fuming (“Hate them all,” “I want them to go back to their own country”), feeling that everyone is against her (“3 against 1!!”), feeling she is being treated badly (“They make me feel like the ugly duckling”), and seeking to gain attention (“I’ll run away and never come back and then you’ll all be sorry!!!”). She retreats to her room trying to find an outlet to speak. The diary and English were powerful tools that allowed her to speak. English was my secret code, since my siblings were unable to read it. However, by carefully cutting around and pasting my brother’s picture, I may have also wanted them to know I was saying something about them. In reflecting on her story of her childhood, Jeannette Winterson (2011) describes what it felt like for her when her parents locked her in the coal-hole. She states,

I made up stories and forgot about the cold and the dark. I know these are ways of surviving, but maybe a refusal, any refusal, to be broken lets in enough light and air to keep believing in the world—the dream of escape.

(p. 21)

Writing about “them” and how they positioned me may have been a way of survival, a way of maintaining my difference from them and sustaining my position as the “rightful,” legitimate owner (“This is my home and my remote control and my parents and my country!!!!!!!!”).

It is not uncommon for children of immigrant parents born in the US either to be the only members of the family who speak English or for children and parents to converse by mixing English with another language, but because of the dynamics of my family during those years, i.e. my half-siblings not being able to speak English, this ordinary ability of speaking English became a special feature in our house. I became of value to my half-siblings, and my ability to speak English with what they called a bonto bareum [native pronunciation] was something useful to them. Activities that involved speaking English, such as speaking to someone over the phone, receiving deliveries, writing letters to boys, and looking over their homework, were tasks they reserved for me. English was my specialty: what defined me as different from them while at the same time what brought me closer to them. When they began to communicate in English and no longer needed my help, we spoke regularly in what was popularly known at the time amongst Koreans in our community as “Konglish,” a mixture of Korean and English that created a specific way of speaking and communicating within and amongst members of the Korean or Korean-American community that we became a part of. Even then, when there didn’t seem to be any struggle for language, there are various connotations in my diaries showing that I secretly perceived myself to be the “real” speaker of English. From another angle, it is also not uncommon for children born to Korean immigrant parents to speak Korean with varying degrees of fluency without much desire or anxiety to speak like a “native Korean speaker,” but while desiring to maintain my difference, I also wanted to fit in, to speak like they did, to speak Korean in a way that didn’t set me apart. These centripetal and centrifugal forces, the push and pull, the contradictory desires and acts, were always present in my relationship with them, in the spaces we had to occupy together.

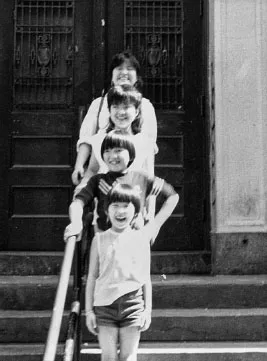

Pic. 1.4 My half-siblings (from top to bottom and eldest to youngest): Kristine, Anna, Ken, and me, in front of the junior high school we all attended. New York (1984)

Having to share the space at home, receiving only partial attention from our parents, suddenly having to wear only hand-me-down clothes, were less than desirable experiences while I was growing up, but my siblings’ unexpected arrival in my life, our “3 against 1” dynamic, the linguistic differences, and the tensions between us also gave me the opportunity to grow up with various cultural discourses and practices, experience beliefs of ownership, feelings of being out of place, and develop ways of escape through language and writing. My multilingual practices and dispositions, as I understand them today, are rooted in the dynamics of these early years, shaped by the changing structures of my family.

Outside of home and towards the beginning of my teenage years I began to feel a disinclination to speak in any language. Even twenty-two years after the experience, I find myself tracing my silence back to a particular relationship I had during my life in New York, which is the focus of the next section. In critically reflecting on that relationship now, I realize there are different dimensions to those experiences I can learn from in relation to the tensions of feeling “out of place.”

Section 2: Gina Kang

In junior high school, I became friends with Gina Kang, a trendy Korean girl who had emigrated to New York at the age of four. Gina took me to pool halls, clubs, and gang houses, taught me how to smoke, and how to put on makeup; she cut my hair and lent me her clothes. She would often remind me that if I were ever in trouble, she’d “have my back,” meaning she’d get into a fight with others for me. We slept over at each other’s homes frequently and soon people thought we were like twin sisters. Gina, to me, was different from other Koreans/Korean-Americans/Americans that I knew at the time, and the feelings, behavior and utterances that were produced in my relationship with her and her world were equally new to me. Being with her made me realize the degree of my desire to break free from norms and the extent of my capacity to do so, but also how strange it felt when I did speak, dress, behave and live the way she did. To me, Gina symbolized disruption, and her uninhibited sense of fear drew me to her. We hardly ever spoke in Korean, but when she did, it was as if she was translating expressions in English using derogatory language that I understood but couldn’t imagine saying to anyone in Korean. In English, her sentences didn’t necessarily consist of many swear words but she had a way of combining words that conjured a more graphic image of certain derogatory statements, such as “I’ll rip her ass apart” or “pull out her eyelashes one by one.” Even at the age of thirteen, Gina had various experience with boys, and she cut class most of the time to go to pool halls in Astoria, Queens to meet up with Chinese gangs she hung out with. She took me to these places and introduced me to these people. The guys would often be dressed in black, their hair dyed orange, layered, usually standing tall with hairspray, and they wore yellow gold chains and round jade necklaces that hung on red strings around their necks. Hanging out with them made me feel “cool.”

In the dark, smoke-filled pool halls in basements where we gathered every morning, drinking and flirting with older guys, I was free from any sense of pressure that had to do with school, family or life goals that my friends seemed to be worried about. I thought I was engaged in something deeper and more philosophical in life than other kids my age were involved in, i.e. school tests, what high school would be like, and what to wear to school every day. I was part of matters more important, such as thinking about money, having what I thought of as mature relationships, and not being controlled by society’s rules. I wanted to believe that I had outgrown my former peers at school, but entering that dark pool hall every morning, I couldn’t shake off the lurking sense that something was wrong, that this wasn’t where I should be at ten o’clock every morning, that I could never get comfortable with this kind of lifestyle. I knew I didn’t belong there, with Gina, in that space, with her friends, speaking their language. Fear and nervousness that trouble was waiting for me around the corner weighed on my mind constantly.

Gina was even shorter than I was at the time (about 5 feet 2 inches) and very thin, but there was power in her appearance that could intimidate others. The choppy layered and dyed hairstyle, the slight slit of the black liquid eyeliner that ran across her eyelids, the dark auburn nail polish and lipstick, the expensive black clothes she stole from malls, the big hoop earrings and the cigarette she usually had pinned between her fingers became my image too. Even though she was nice to me, being unable to have any sense of what she was thinking about, what made her vulnerable or how she would react to a certain comment, made me stammer while talking to her. I grew increasingly uncomfortable with her and her group of friends and sensed deep trouble as I became increasingly more involved in her world. My diaries of that period are filled with panic at the thought of being left behind at school even though I never thought of myself as a devoted student.

I decided to stop meeting Gina and try going back to school. This infuriated her and we had several malicious verbal and physical arguments. From then on, there was endless gossiping and threatening phone calls. I have not been able to forget two warnings from Gina that terrified my twelve-year-old self when she uttered them: “I’ll burn down your house” and “I’ll scratch your eyes out if I ever see you.” For whatever reason, Gina left me alone and the result was that I finished the seventh grade. However, back in school, I had an unavoidable lurking feeling that someone would protest that it wasn’t fair to the other students, after all the school days I had missed, to allow me to pass. I felt increasingly like a fraud. My peers had worked hard. I was cheating. Coupled with this feeling, I became fearful of the Asian youth culture in New York, particularly of those who had Korean ancestry and spoke English: in short, people who had my particular cultural background and linguistic abilities. I wanted to withdraw from people like me. I wanted to be with others completely different from me, which wasn’t very difficult given the majority of the students in this school were Italian-Americans. They couldn’t make me feel out of place since I didn’t belong with them in the first place. This understanding that I could be “neutral” with those who were not like me provided me with some feeling of comfort.

The net result of these experiences with Gina, school and my feelings about those who resembled my cultural and linguistic characteristics was to make me deeply self-conscious. At any sighting of Asian teenage girls, I learned to instinctively turn or look the other way. I was quiet at home and at school and all I wished for was to flee from the space of New York and start over again. New York was my physical home but I didn’t feel I belonged there or to my family or the life my parents built in that city. Similar to Said’s (1999) description of not feeling quite at “home” and in describing his perception of how his family was seen in Cairo, I felt New York was “a city I always liked yet in which I never felt I belonged. There was something ‘off’ and out of place about us (me in particular), but I didn’t yet quite know why” (p. 43). Reading through diary entries, I thought at the time that if I could have been a full-Korean, i.e. Korean-Korean, or a white American, my life would have been so much easier.

Social, political, cultural and historical dynamics are undoubtedly a part of the construction of feelings of being out of place, but in writing this reflection of my relationship and experience with Gina, the importance of locating particularities, that is, particular events, people that cross our paths, emotions that are felt that guide us to make certain decisions, is made clear to me. Affect, in particular, stands out in my experience with Gina and school. Feelings of discomfort, fear, nervousness, trouble, intimidation, anxiety, panic, fraudulence, foreignness and neutrality fill my memories of this period, but they are also not expressed as passive states of mind that I have experienced; rather, they are denotative of how they guided me to take some form of action, i.e. to stop meeting Gina, go back to school, withdraw from speaking, join “other” groups, and so on.

In her study of gender enactments in immigrants’ discursive practices, Vitanova (2004) points out that where emotional struggles are involved in participants’ stories, the tone quickly changes to containing “the seeds of resistance and future action” (p. 274). Drawing on Lorde (1984) and other discourse analysts, she takes the position that feelings and emotions are discursive phenomena and should be studied as talk that performs social actions, and they can also serve as a guide to social analysis. The workings of affect are unpredictable, uncontrollable and not fully up to us to control (see Ahmed, 2004), but this does not mean affective ‘lines of flight’ (Deleuze & Guattari, 1980) cannot be empirically traced. Emotions are an assemblage of the spatial, semiotic, discursive, and historic; thinking about them seriously gives us an opportunity to see the flows, intensities, spontaneity and complexities of affect as it moves with language in situated practices. Focusing on my emotions and how they have guided me moves me away from the powerful hold Gina’s words have had on me to think about how our constantly developing dispositions negotiate the familiar and unfamiliar, old and new feelings and experiences in different spaces and practices.

At the end of the seventh grade, I got my wish to leave New York and move to Seoul to live with my cousins. There, I experienced a different kind of “out of placeness” that made me feel I belonged back in New York.

Section 3: Moving to Seoul (1991–1992): Attending an International School

I moved to Seoul for one year and lived with my cousins while I attended an International School. I remember my mother showing me brochures of the school and pointing out that a high percentage of high school graduates from the school were accepted into Ivy League universities, with several being accepted into Harvard. Although I understood my mother’s aspirations and efforts to provide me with an “elite” ...