![]()

1

Developing a Theoretical Orientation to Performance Excellence

Joanna M. Foss, Emily Minaker, Chad Doerr, and Mark W. Aoyagi

People have moments in their lives when they feel like they were able to perform at their best, when it mattered most. These fleeting moments are often labeled peak experiences or optimal performances. Performance excellence captures these moments but also broadens the perspective and encapsulates performing at a consistently high level over time and enjoying the process of performance. The field of sport and performance psychology (SPP) has dedicated itself to understanding what underlying mental and emotional factors contribute to a performer getting the most out of his or her ability in those important moments as well as in the moments training outside of the spotlight and developing capability. Professionals in the field of SPP have developed effective and complex theoretical understandings that guide their work. These theories help consultants conceptualize and understand why performers may experience a peak performance, perform consistently well over time, and, as is bound to happen, perform less than desirably at times. They also inform and provide rationale for the use of interventions targeted at training specific mental skills that will help their clients perform to their highest abilities.

Although many would argue for the importance of practicing from a theoretical orientation, a gap exists within the SPP literature around this issue. Steps have already been taken to remedy this gap (see for example Aoyagi & Poczwardowski, 2012), and continued attention within the literature will support this foundation of SPP practice. Thus, the purpose of this chapter is to identify the current state of theory within SPP, to discuss the importance of developing and of working from a theoretical orientation, and to propose a model to guide students and other practitioners through the process of developing their own theoretical orientation to performance excellence.

Theoretical Paradigms in SPP

When examining the state of theoretical paradigms in SPP, it is first important to define what is meant by a theoretical paradigm. Terms such as theory, model, philosophy, and frameworks are often used semi-interchangeably within the SPP literature. This has led to confusion as each of these terms has a particular nuance (Aoyagi, 2013). A theoretical paradigm refers to a framework with a high level of abstraction (Prochaska & Norcross, 2010), which guides practitioners in attaining a global understanding of the area of interest (e.g., performance excellence) and is typically built from several theories (i.e., explanations of specific phenomena). Additionally, theoretical paradigms enable practitioners to understand and to explain why certain characteristics or interventions impact clients in the ways that they do (Aoyagi, 2013). Thus, a theory is abstract enough to allow practitioners to make sense of vast amounts of information or to generate hypotheses based on incomplete information.

Currently, SPP literature tends to rely on models as opposed to overarching theoretical paradigms. These models may be based on theoretical paradigms; however, they often lack the depth or the ability to predict behavior that is expected when utilizing a theoretical paradigm. For example, the psychological skills training (PST) model often utilized in SPP reflects aspects of cognitive-behavioral therapy; however, it lacks the ability to explain behavior inherent in its parent theory (Tod, Andersen, & Marchant, 2009). In addition to models, specific theories are sometimes confused with theoretical paradigms. An example here is Self-Determination Theory (SDT [Ryan & Deci, 2000]), which has been widely adopted within the SPP literature to explain motivation due to its well-researched and practical applicability. However, SDT is a theory, as opposed to a theoretical paradigm, and therefore is not at a high-enough level of abstraction to explain overall behavior, performance excellence, or areas outside of motivation. SDT may be a component of a theoretical paradigm but is not one itself. Rather, theoretical paradigms can inform practitioners to intervene on a wide range of issues with performers as opposed to specific subsets of their presenting concerns. The limited scope of information coverage that models and theories provide clearly does not allow for practitioners to make sense of large amounts of information from various contexts.

Furthermore, the theoretical paradigms that are utilized in SPP are often taken from general psychology. These general psychological paradigms have been developed to “explain and understand pathology, and to assist practitioners in preventing, eliminating, or assessing, symptomatic, maladaptive, or undesired behavior” (Aoyagi, Portenga, Poczwardowski, Cohen, & Statler, 2012, p. 33). However, the needs of the populations with whom SPP practitioners work are often different from the needs of populations experiencing psychopathology. General psychology theoretical paradigms can certainly provide a framework for practitioners to support athletes, and in many cases may contribute to performance excellence; however, theoretical paradigms specific to understanding and facilitating performance excellence would better guide practice for the provider seeking to offer performance excellence services and even more importantly for clients seeking performance excellence consultation (rather than therapy).

Performance psychology was defined by the American Psychological Association Division 47 Practice Committee as “the study and application of psychological principles of human performance in helping people consistently perform in the upper range of their capabilities and more thoroughly enjoy the performance process” (2011, p. 9). Although this is the definition of SPP, it is clear that there is a distinct lack of theoretical paradigms describing the underlying constructs behind performing to the upper range of their capabilities (Aoyagi & Poczwardowski, 2012). This is not to say that practitioners are atheoretical in their approaches to working with athletes; however, few practitioners directly working with performers in the field have articulated their theoretical paradigms in the literature and exposed them to scientific scrutiny. In an age of accountability and evidence-based practice, further attempts to address this gap would enhance the scientific credibility of the field.

It is from theoretical paradigms that practitioners develop their Theoretical Orientation to Performance Excellence (TOPE). A TOPE is a “consistent perspective on human performance, psychological facilitators and inhibitors of performance, and the mechanisms of influencing performance excellence” (Aoyagi, 2013, p. 142). This is comparable to practitioners within the field of psychology working with clients from the lens of specific theoretical orientations (e.g., cognitive-behavior therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy); however, the TOPE is meant to inform reaching performance excellence and high-level functioning, rather than the reduction of psychopathology.

Why Develop a TOPE?

Developing a TOPE is a task that should be embraced by future professionals in SPP, as it provides support and guidance for understanding issues and proactively informs service delivery (Christensen & Aoyagi, 2014; Henriksen & Diment, 2011; Stambulova & Johnson, 2010). We believe that a TOPE gives you a framework from which to build on for the remainder of your career and challenges you to engage in a process of lifelong learning. However, developing a TOPE can often be seen as difficult, and sometimes tedious. “I am only a first year student with little experience, so why am I developing a TOPE?” is a question I (EM) asked myself before developing my own TOPE and one that was frequently echoed by my classmates. I soon realized that this was precisely the reason why, as a novice consultant, I needed to develop a TOPE. With my lack of experience in SPP fieldwork, it was imperative that I had a foundation of theory to guide future service delivery. This strong theoretical underpinning provided a basis for determining the best strategies or interventions to use with my clientele. By embracing the uncertainty and realizing the task was not as daunting as first thought, I was able to see the increased confidence it would bring me in working with a client for the first time. It also made service delivery personally meaningful and more enjoyable (and less stressful!). Answering the question of “why” made the process more sensible, and I was able to see the benefits in guiding my applied work. (See Chapter 7 for in-depth exploration of initial practicum experience.)

Developing a TOPE represents a sophisticated approach to service delivery. It allows you to proactively conceptualize how to move a client toward performance excellence, as opposed to reactively responding to issues by eclectically selecting interventions. As a novice consultant, I (JF) found myself trying to cater to coaches’ desires or “in the moment” problems rather than stepping back and viewing client concerns from a wider lens. I picked interventions that would alleviate the current problem as opposed to considering the “real issue” behind the problem. I recall one of my first consulting experiences working with a high school soccer team where this issue was particularly present. During that time, I had no overarching plan for what I intended to do with the team. Instead, I would take observations from practice or from the game and then do a session on related topics the following week. For example, there was a game where the team became very angry and frustrated with an opponent, so I followed with a session on composure. In approaching from this angle, I missed social and cultural considerations that impacted the athletes’ emotional states. Other times the coaches or I would notice players going through the motions in practice, so I would follow with a session on commitment or on the benefits of deliberate practice. Reflecting on that experience, there seemed to be two main factors working into the style of my consulting: lack of big picture planning and lack of confidence in my own consulting. It was much more comfortable to respond to immediate concerns and to feel like I was addressing topics the coach wanted rather than taking a more long-term approach to my work.

This is much different than the way I (JF) approach my consulting today. I currently begin with the end in mind (Covey, 1989) for my work with teams and with individuals. Rather than react to problems, I try to conceptualize what is needed for performance excellence in specific domains and then proactively build those skills throughout the off-season and season. For example, I more recently worked with an individual closed sport. I began by observing practice and ultimately decided that the performance excellence goal was to “win” each individual skill execution by giving each instance full focus, intensity, and trust. With that end goal in mind, I created a general plan for which sport psychology concepts and applications would be needed to reach that ability based on my TOPE. This plan was general to allow for flexibility within the season while still serving as a guide for ym work. In general, operating from a TOPE required that I step back and practice my skills in conceptualization about both what was occurring and why it might be, and then to proactively address the concern. This critical thinking ability is a skill that I continue to develop when working with clients and teams.

Taking into account a wider view of client concerns also can help develop strategic mental programs when working with teams. In developing my TOPE, I (EM) was able to understand why I was selecting particular interventions and to formulate a program that allowed me to address issues before they arose. Despite the planning, my formulated program was never executed perfectly, due to unforeseen circumstances that naturally arise when working with SPP clients. However, my TOPE still gave me a direction to work toward and something to fall back on when presented with unique challenges within the sport and performance domain (Poczwardowski, Sherman, & Ravizza, 2004). Focusing on the process (versus the outcome) during the development of my TOPE allowed me to understand the importance of maintaining a flexible mindset. When unexpected circumstances arose, I was able to be proactive in choosing interventions to inform future practice. An example of this was during my first term as a novice consultant when I was brought in to work with a team because they were having a lot of issues with player attitudes and team cohesion. I was aware of the unpredictable environment that I was walking in to, as before I conducted my first session I had spent two weeks observing practices and games and getting to know the players. In my third session with the team I was leading an activity about creating a team vision. The session did not go as planned, as the players turned the session into an opportunity to discuss the issues they had with each other and the coach. It was in this moment when my session was quickly turning into an unproductive, anger-fueled conversation that I realized my TOPE had already proactively informed my service delivery. Due to the time I had taken to get to know the team, I was able to create a space where they felt comfortable openly discussing issues. My TOPE allowed me to know in that moment the most beneficial intervention was not for me to follow my own agenda. Therefore, I was able to move the session along to better suit the team’s needs in discussing team issues and allowing them a safe space in which to do so. I quickly learned that having a flexible mindset and being proactive in choosing interventions were key to helping this team and informing my future practice. In the end, we did end up developing a team vision, and it greatly increased cohesion within the team; however, if I was not grounded in a theoretical foundation, my relationship with this team would have been more self-serving and less beneficial to the client.

Focusing on learning major theories and theoretical integration at the beginning of my training was frustrating at times. I (CD) felt a strong urge to simply learn a set of interventions, and I wanted to be told exactly what to do in order to “fix” any problem that arose with a team. I was impatient, in that I wanted to know the secret formula to peak performance and teach that the same way to all my future clients. However, as great athletes know, a deep internalization of fundamentals is the key to high performance. Therefore, initially focusing my education on pre-existing theories and models of human mental behavior, and deeply reflecting on what high performance personally meant for me, allowed me to develop a strong ability to understand and conceptualize. While I was not the best at presenting and providing interventions for athletes at the beginning of my training, the fundamental ability of conceptualization through my developing TOPE fostered my creativity and allowed me to understand, connect, and provide the appropriate interventions for the performers I was working with. Instead of my initial question (“How do the best consultants work with their clients, and how can I imitate them?”), I began to ask how the field of SPP can be better and think in new ways to develop more effective services.

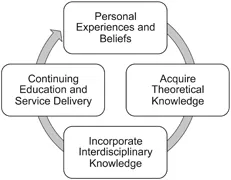

Figure 1.1 Model for Developing a Theoretical Orientation to Performance Excellence

In sum, future professionals in the field of SPP would benefit from developing a strong TOPE. It informs applied work and provides a sense of security and direction in the often nebulous and sometimes chaotic world of consulting. We suggest that novice consultants developing their own TOPE take a sense of fulfillment in that not only are they benefiting their own future service delivery but they are also contributing to the advancement of SPP by fostering new and creative methods to intervene with performers that are theoretically and scientifically based.

Model for Developing a TOPE

As individuals who have developed our own TOPE, we understand that the process of developing a TOPE can seem overwhelming. The remainder of this chapter will discuss a proposed model that will help guide students and novice practitioners in formulating their own TOPE (see Figure 1.1). These sections will discuss both the process of succeeding within each stage and personal themes that emerged for us authors while undergoing the process ourselves. These will serve to normalize some aspects of the experience and to offer advice for students that we believe would be useful to know earlier in development. However, this is not to say that these experiences are exhaustive or typical of all students who undertake this process.

Personal Experiences and Beliefs

We suggest that your personal experiences and beliefs form the foundation of your theoretical orientation to performance excellence. What are your own thoughts on how to achieve performance excellence? What makes sense to you based on your history and the knowledge you have already accumulated? Novice consultants developing a TOPE with no applied SPP field work may experience difficulty when first facing the task of writing a theoretical orientation, which was a task in one of the early courses in our graduate program. After we read Expert Approaches to Sport Psychology: Applied Theories of Performance Excellence (Aoyagi & Poczwardowski, 2012) and examined highly regarded SPP professionals’ theoretical orientations, it was encouraging to see how a TOPE can evolve over the years. However, the realization that the basis of these highly regarded professionals’ TOPE stemmed from their own personal experiences and beliefs made the task of writing my (EM) own theoretical orientation more enjoyable. By ...