![]()

INTRODUCTION

1

In the lower montane forests of the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea, a population of some 14,000 slash-and-burn horticulturalists known as the Fore (pronounced FOR-AY) tend gardens of sweet potato, taro, yam, corn, and other vegetables. They also grow sugarcane and bananas, keep pigs, and, in the sparsely populated regions near their southern boundaries, still hunt for birds, mammals, reptiles, and cassowaries. Unlike the open country to the north around Kainantu or Goroka, where long-established grasslands prevail, this part of the Eastern Highlands consists of mixed rainforest broken by small clearings and grasslands of no great age. The forest includes oak, beech, Ficus, bamboo, nut-bearing Castanopsis, feathery Albitzia, red-flowered hibiscus, and many other species used for food, medicines, and stimulants, as well as salt, fibers, and building materials.1 Pandanus grows at higher altitudes. The ground is covered with a wealth of edible shrubs, delicate tree ferns, fungi, and creepers. Red, white, and salmon-colored impatiens sparkle in the shafts of sunlight beside forest paths, and fems, orchids, and rhododendron grow as epiphytes in the canopy overhead. The forest rings with the sound of birds feeding on tall fruit trees.

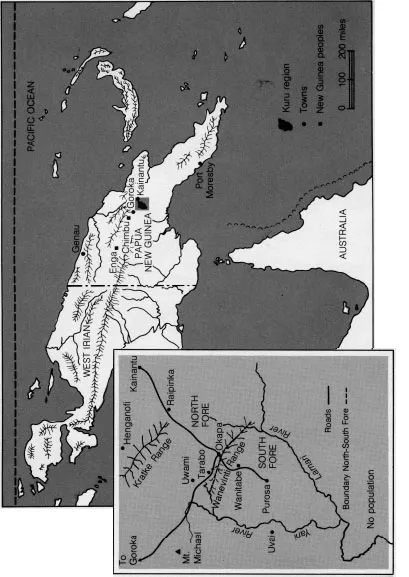

The Fore-speaking population lies in the wedge created by the Kratke Mountains to the north, and the Lamari and Yani Rivers to the east and west. Although the terrain ranges in altitude from the mountains at 9,000 feet to southern valleys at 2,000, gardens and hamlets are scattered across the zone between 7,500 and 3,500 feet, where the population has access to both montane and lowland environments. Hamlets typically consist of seventy to 120 people, living in twelve to twenty houses, and their adjacent gardens. Surrounded on three sides by populations speaking Gimi, Keiagana, Kanite, Kamano, Auyana, Awa and Kukukuku (also known as Anga), the Fore are reluctantly penetrating the uninhabited region to the south. Stories of illness and hardship characterize their view of existence in these frontier communities.

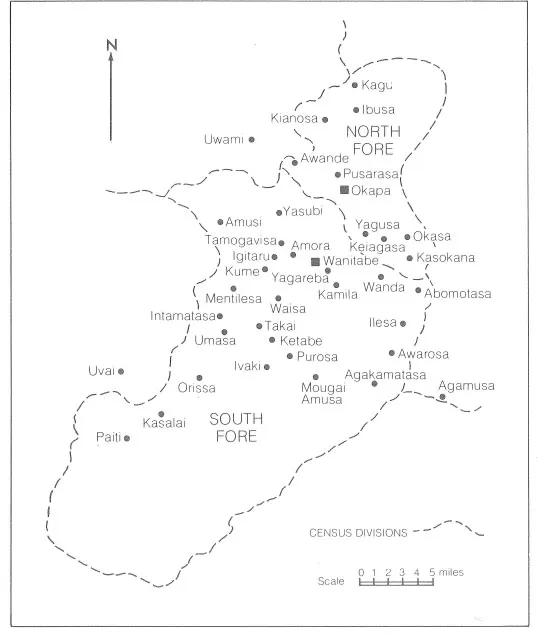

MAP 1 The Kuru Region in Papua New Guinea

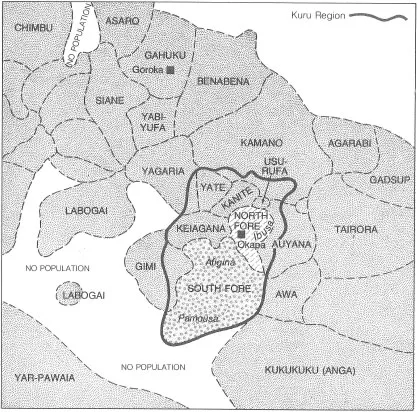

MAP 2 The Fore and Their Neighbors

SOURCE: Adapted from E. Richard Sorenson, The Edge of the Forest (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Inst., q2976), p. 20 © Smithsonian

The Fore represent the most southerly extension of the East New Guinea Highland linguistic stock,2 but they have much greater genetic heterogeneity than most linguistic groups in the Eastern Highlands. The Fore, with a remarkably flexible kinship system, do not constitute an isolated breeding population. Genetic studies show their close association with populations in two directions. To the northwest, they are most closely associated with the Kamano, Gimi, and Keiagana, and to the southeast with the Awa, Auyana, and Tairora.3 Kukukuku populations across the Lamari Valley and the Yar-Pawaian groups beyond the uninhabited zone appear to belong to different linguistic, genetic, and cultural communities.

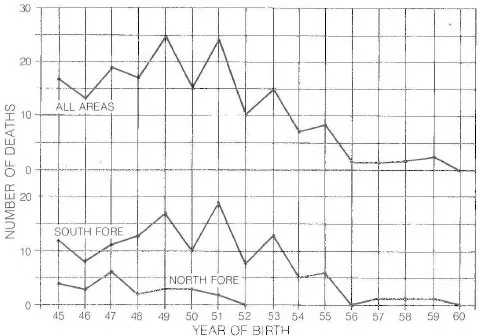

The Fore are afflicted with a rare disease. Since record-keeping began in 1957, three years after the Australian administration established a patrol post at Okapa, some 2,500 people in this region have died from kuru, a subacute degenerative disorder of the central nervous system. Approximately 80 percent of all kuru deaths have occurred among Fore-speaking people, with the remaining 20 percent striking neighboring populations. In the early years of investigation, over 200 patients died annually, which at that time approached 1 percent per annum of the affected population.4 In recent years, kuru rates have steadily declined, and in 1977 only 31 persons died of the disease. Following several decades in which kuru was the major cause of death among the Fore, the disease is rapidly disappearing.

My main focus is on the 8,000 South Fore. Identified by Australian government officials in the 1950’s as a single census division within the Okapa Subdistrict, South Fore is separated from North by a low mountain range (Wanevinti) that hinders but does not preclude contact between the two populations. Marriage partners, trade goods, food, refugees, illnesses, and ideas move between North and South, but South Fore social life is focused on the lands sloping southward from the mountain barrier. There two dialect groups (Atigina and Pamousa) with a high frequency of cognate words are recognizable. The two southern dialects have more in common than either has with Ibusa, the dialect of the North Fore.6 It is among the South Fore that the incidence of kuru has been highest. Between 1957 and 1968, over 1,100 kuru deaths occurred in a South Fore population of 8,000, and most cases reported for 1976 and 1977 come from this region. Since kuru is predominantly a disease of adult women—the childbearers, pig tenders, and gardeners—its effects on Fore society have been particularly deranging. When the incidence of kuru reached a peak, in the 1960’s, the South Fore believed their society was coming to an end. And indeed, with their high female mortality and low birth rates, in the early 1960’s their numbers were truly declining. South Fore were aware that the disease was striking them hardest.

This book discusses the Fore response to kuru in the 1960’s, when the epidemic was at its height. In Chapter 2, I trace the interest of Western scientists in the disease, from the time they learned about it in the early 1950’s to the present. Chapter 3 surveys Fore medical disorders, and shows that apart from kuru, their health status resembles that of kuru-free populations in the Eastern Highlands of New Guinea. Chapter 4, an analysis of South Fore kinship, indicates that Fore establish ties by demonstrating commitment to a relationship. Kinship is as often based on common interest and support as it is on heredity.

FIGURE 1 Number of Persons Dying of Kuru (since 1963) for each year of birth from 1945

SOURCE: Adapted from Hornabrook and Moir 1970

In Chapters 5 and 6, I present Fore views of the cause of disease, and suggest that Fore beliefs are appropriate to a particular way of life and period of time—that is, to communities of partially intensive swidden horticulturalists in the 1960’s. In the three decades since the Australian administration at Port Moresby sent the first patrol through Fore territory, both their mode of existence and Fore beliefs about it have undergone rapid change, allowing us an opportunity to observe the ways that philosophical systems depend on context. A new way of life gave rise to greater manipulation of the environment, and to differences in rank requiring the coercion of others in order to maintain an elevated position. New diseases also took their toll. As these changes occurred, ghosts of the dead and spirits of the forest receded, displaced by growing numbers of sorcerers.

The early 1960’s were crisis years for the Fore. They hunted for sorcerers and consulted curers (Chapter 7), and finally they called great public meetings (Chapter 8). There, they denounced the performance of sorcery that was decimating their women and creating a wasteland. Sorcerers were said to be the agents of all that was wrong with the human condition. They were seen as the negative of all that is fine, good, and moral, as instruments of impoverishment and decline, and as a burden on the community (Chapter 9). Notions of sorcery, witchcraft, and pollution emerge as ideologies of containment, by which wielders of power attempt to degrade their opponents, coerce social inferiors, and allocate resources. Sorcerers, witches, and polluters therefore have universal attributes. They appear in different manifestations and with varying powers of retaliation in New Guinea and elsewhere. The direction from which they project their feared energies is a clue to an asymmetrical interchange, either between individuals or between regions (Chapter 10). Chapter 11 considers the intricate historical and ecological contexts in which populations respond to the threat of extinction. The new chapters, 12 and 13, describe many recent changes, both material and spiritual, and how these shifts in daily life provide a parallel reading of local medical beliefs and practice.

In the search for the cause of kuru, Western science unraveled a biological mystery; the solution has applications for neurological afflictions that range far beyond the borders of New Guinea. The Fore analysis of the problem revealed more about victimization, and told us more about ourselves. While their medical observations were frequently accurate, they were embedded in social codes, and in messages about the nature of existence. In their statements about the cause of disease, the Fore also considered those conditions under which a threatened society might ultimately endure.

![]()

KURU AND SORCERY

2

As he passed through the hamlets at Amusi during an Australian government patrol in the South Fore region, Patrol Officer McArthur made a significant notation. “Nearing one of the dwellings,” he wrote in August 1953, “I observed a small girl sitting down beside a fire. She was shivering violently and her head was jerking spasmodically from side to side. I was told that she was a victim of sorcery and would continue thus, shivering and unable to eat, until death claimed her within a few weeks.”1 Although the disease had been mentioned in earlier government reports,2 this was the first official description of kuru, a fatal neurological disorder very common among Fore, and present to a lesser degree among neighboring groups, but unknown elsewhere in the world. The discussion that follows presents kuru as a disease entity as perceived by Western observers, and follows the evolution of medical thought over more than two decades. Western scientists now consider kuru to be a slow virus infection spread by the ingestion of human flesh. This view contrasts with that of the Fore, who remain convinced that the illness results from the malevolent activities of Fore sorcerers.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF KURU

A Fore word meaning trembling or fear, kuru is marked primarily by symptoms of cerebellar dysfunction—loss of balance, incoordination (ataxia), and tremor. An initial shivering tremor usually progresses to complete motor incapacity and death in about a year. Women, the prime victims of the disease, may withdraw from the community at the shock of recognizing the first symptoms—pain in the head and limbs, and a slight unsteadiness of gait. They resume their usual gardening activities a few weeks later, struggling to control their involuntary body movements until forced by gross physical incoordination to remain at home, sedentarily awaiting death.

MAP 3 Fore Settlements

The clinical progress of kuru is remarkably uniform. It has been divided into three stages by Dr. Carleton Gajdusek, who has made extensive clinical studies of the disease:

The first, or ambulant, stage is usually self-diagnosed before others in the community are aware that the patient is ill. There is subjective [self-perceived] unsteadiness of stance and gait and often of the voice, hands and eyes as well. Postural instability with tremor and titubation [body tremor while walking] and ataxia of gait are the first signs. Dysarthria [slurring of speech] starts early and speech progressively deteriorates as the disease advances. Eye movements are ataxic…. A convergent strabismus [crossed eyes] often appears early in the disease and persists. Tremors are at first no different from those of slight hypersensitivity to cold; the patient shivers inordinately. Incoordination affects the lower extremities before progressing to involve the upper extremities. Patients arising to a standing posture often stamp their feet as though angry at them. In attempting to maintain balance when standing, the toes grip and claw the ground more than usual. Very early in the disease the inability to stand on one foot for many seconds is a helpful diagnostic clue…. In the latter part of this first stage, the patient usually takes a stick to walk about the village unaided by others.

The second, or sedentary, stage is reached when the patient can no longer walk without complet...