![]()

CHAPTER 1

Why the Stock Market and its Efficiency are so Important

This chapter attempts to answer the following questions: What is stock market efficiency? What is market abuse? Why is stock market efficiency so important for the economy and why is stock market abuse so bad that people are imprisoned for it? First, however, why are the stock market and its efficiency so important? In a sentence: because the stock market channels our savings, and those from other nations, if we have a good and well-run exchange, into production and productive services and, if it is efficient, the stock market channels this money into those areas that most require it.1

Today, we take the stock market very much for granted. The creation of an economy in which limited liability companies could easily be formed and their shares freely sold and transferred between investors dates from, and very much underpinned, the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain. To take advantage of the new opportunities for automation and economies of scale, businesses needed to operate on a much larger scale than hitherto. For the first time, companies with limited liability and transferable shares enabled entrepreneurs to raise funds on the scale they needed and from people who were not involved in the running of their businesses (Barnes and Firman 2002). The concept of shares being easily transferable was a brilliant idea. It enables investors to invest in a business for just as long as they wish. When they wish to end their interest, they are able to sell the shares without harming the company whatsoever. An open and free market allows them to sell shares easily. From the company’s point of view, it has long-term capital in the form of shares for as long as it wishes. Also, it is an easy mechanism through which the company can raise new capital.

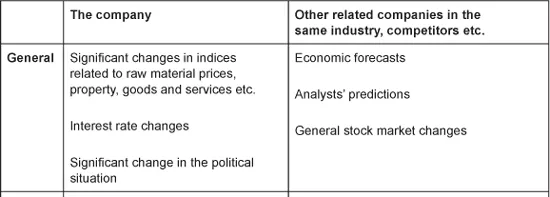

The price of a share is determined by supply and demand. It is what investors are prepared to pay for it – at that time – and what others are prepared to sell it for. Its price is, therefore, what an investor believes it is worth. A share price reflects all known information and represents the collective beliefs of all investors about the business’ future prospects. When an investor is considering buying a company’s shares, they will attempt to assess how much the shares are worth by determining how much money they will receive in future dividends from those shares and how much the shares are likely to be worth when the investor comes to sell them. The investor will also consider how risky the shares are, and can only do this by attempting to place a value on the company’s business and its ability to earn profits in the future. Table 1.1 provides a list of examples of information likely to affect a company’s value and, therefore, its share price.

In this sense, the stock market is ‘efficient’. If an investor thinks a share is worth more than the current market price, they will buy it – or at least they should – and as many as possible, if they have the money. Similarly, if they think the value of a stock they own is less than the market price, they should consider selling it. If they think the value of a share is about the same as the market price, then they should do nothing. In other words: if they think a share is ‘undervalued’ they will hold those they already have and buy more but if they think it is ‘overvalued’, they will sell it and invest their money elsewhere. Therefore, if there are enough investors interested in the share, with enough money to buy and sell in large quantities, its market price will soon adjust to their collective beliefs. It is sometimes said that a speculator performs a useful and valuable role in the market by buying what they consider to be undervalued shares and selling overvalued shares. Most large stock exchanges, certainly the LSE, are regarded as being efficient because most listed companies’ shares are traded in sufficiently large volumes. There may be a few stocks in relatively small companies that are not sufficiently traded – or there is not a sufficient amount of interest in them – for this to not to occur. The market in these ‘thinly traded’ stocks may be inefficient at times and it is open for speculators to profit from such situations. Nevertheless, the large exchanges are regarded as efficient, both internally and across exchanges. That is, the price of a company’s shares is likely to be the same, or about the same, across other exchanges as otherwise investors (known as arbitragers) will buy on one exchange and sell on another at a profit. The action of these arbitragers, or even the prospect of it, is sufficient to ensure that the prices across these exchanges are about the same.

Table 1.1 Examples of new pieces of information likely to affect a company’s share price according to their type

Also contributing to its efficiency is the fact that the stock market is dominated by large financial institutions and investment funds that are managed and advised by ‘professionals’ – financial analysts. Part of their job will be to seek out under- and overvalued shares and inefficiencies in the market from which they may be able to profit. It is also true that the abler investor makes more money in the longer term because they make consistently better choices and decisions compared with the less able investor who makes weaker decisions and less money. The consequence of this is that the financial markets will be dominated by the decisions of the best investors because it is they who are strong and powerful. (Later parts of this book illustrate how ‘the fool and his money are soon parted’.) In practice, therefore, the prices of the vast majority of companies will not only reflect the collective opinions of investors but that of the professionals and ablest investors. Given the speed of information in today’s world, the ease of access that so many people have to it, and the amount of money that stands to be made or lost in the market, it is very difficult to imagine how it can be anything other than efficient.

What has been said so far relates solely to informational efficiency. The stock market adjusts to new information very quickly. Some say that this is instantaneous, although we will see in later chapters it is quite sluggish. At any time, therefore, a share price reflects all that is known relating to the prospects of the company and the collective judgement of the market as to what it is worth. This has a number of implications.

The first relates to decision-making by individuals and organizations. If the information available to a shareholder is completely up to date, full, fair, reliable and freely available (that is: easily accessible and at zero or negligible cost) then we can truly say there is a fair market in the shares, in which case all investors will have similar information (or at least if they do not, it is their own fault) and market prices will move to reflect these. It follows that not only does an investor have all the information available to make a good decision, they do not have to read, analyse and digest all the information about and affecting the company, because the market has done it for them! Even if they do this and are skilled at analysing such data, they will simply arrive at a similar value for the company as professional analysts – the market price! They have had what economists describe as a ‘free ride’. In fact, we may argue that studying a company’s accounts, analysts’ reviews etc. is pointless because they will (or should) simply lead the investor to the conclusion that the market price is correct and it equals the value of the share. It also follows, therefore, that an investor does not need to read the company’s financial statements but can choose any firm, even at random, and the price will represent the security’s correct value. Some academics argue that the best way of selecting a portfolio of shares is to take a newspaper containing a list of publicly traded shares and stick pins in it at random to select which companies to invest in!

At first glance, this implies that all an investor can do is choose the companies in which to invest in at random, hold them and not trade as there is no point in trading as they cannot beat the market and earn a higher return. By trading, the investor will simply incur unnecessary trading costs. This is incorrect. A better investor will usually earn higher returns than a poor investor – certainly in the long term. Whilst the prudent investor may be able to obtain the same level of returns as the market as a whole by simply holding a representative sample of companies, the bad investor may earn low returns by continually trading, for example, by taking a profit on what had proved to be a good investment and putting the proceeds into a bad investment. Also, the abler investor may earn high returns by making better judgements than others and beating the market by identifying companies that are likely to be successful.

The second implication of informational efficiency relates to the role of the stock market within the economy. Informational efficiency assists in the efficient allocation of resources within the economy. ‘Allocative efficiency’ refers to a situation in which scarce resources are allocated between competing requests in a way that maximizes the net benefit to society in accordance with the wishes of consumers. A company whose products are not in demand, or whose productive processes are inefficient, will not make as much profit as a company whose goods are in demand or which is very efficient. As a consequence, its returns to shareholders will not be as high and it will find raising new capital difficult. A stock market that is allocatively efficient will allocate new funding to the most profitable companies – those most able to provide goods that are most needed and those that are most efficient at providing them.

A good example of this is the rise of hi-tech and Internet-related companies in the USA and UK in the late 1990s. Many new companies were formed that promised huge profits from the information technology revolution and investors clamoured to invest in them in anticipation of the high returns. In the early 2000s the situation was reversed when it was found that not all companies were able to provide the promised returns, and investors became very sceptical about investing in these kinds of companies without certain assurances of a return. As a result, even well-run companies in the sector found it difficult, if not impossible for a period, to raise new funds.

Informational efficiency is a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for allocative efficiency. The market may adjust quickly to news but the information may not be perfect or complete. It is well known that not all costs of production are incurred by the producer and are included in their financial statements. I live both close to a huge power station and the runway of an international airport. I pick up some of their costs (in the sense that the operating costs they actually incur are less than the total cost to society of their operations). They do not have to pay, directly anyway, for my hospitalization and shortened life expectancy from air pollution. As a result, their contribution to society and their profits are both overstated. If airlines incurred the true and total societal costs, not only would they no longer make such large profits, they may actually make losses and certainly would be unable to offer cheap flights in the way they are doing. In short, a capitalist system is not perfectly allocatively efficient. Its merits lie in the speed of allocation.

Also, as with any other market, its participants (in particular, those companies whose shares are traded) will want to exploit their own positions as they pursue their own objectives. Businesses have better information about their business investment opportunities than savers. Invariably, management has an incentive to overstate the value and performance of the business, if only to maximize their salaries and rewards. That is human nature. One need look no further than the collapse of Enron, Worldcom and Arthur Andersen to see how even very large organizations may be brought down if such behaviour goes unchecked.

Savers have an ‘agency problem’ as they wish to know how their investments are faring and the returns they are making (Healy and Palepu 2001). Their agents – the managers who are managing the company on their behalf and the auditors who are checking that those managers are acting properly and accounting fairly – have their own interests at heart. They both have an incentive to provide owners with information that implies the company is doing well. Owners, on the other hand, need to know when it is not.

This problem may lead to a breakdown in the functioning of the capital markets. Say a number of businesses came to the stock market to raise funds. Half of them had good proposals yielding profits to investors and the others had weak proposals with no likely profits. If investors are unable to distinguish between the two groups, they will be unable to identify what are good and bad investments and probably assume they are similar. The result is the good investments are undervalued and the bad investments are overvalued. Clearly, this is a ‘bad thing’. It is bad for investors because they do not know where it is best to invest. It is bad for businesses because those that are more deserving of the new funds are not prioritized but stand alongside those businesses that do not deserve the new investment. Most of all, it is bad for society because scarce investment resources are not directed to those areas most in need. Further, it does not encourage individuals (and, therefore, a nation as a whole) to save and invest. In short, it is allocatively inefficient.

A similar result occurs if we substitute into the illustration ‘honest’ and ‘dishonest’ for ‘good’ and ‘bad’ businesses. Investors may stand to lose their money by being unable to distinguish between honest and dishonest investments. I remember once speaking with a wealthy student from a poor African country. I asked her why she did not invest money on her country’s stock market. She laughed with derision remarking something along the lines that ‘you must be joking; they are all corrupt’. As a result, her family invested its money in more secure and (probably, therefore) more prosperous countries. The economic consequences for her country (once rich but now poor) are obvious.

This is a well-known problem in economics. It is known as the ‘market for “lemons” problem’ (Akerlof 1970), a reference to the US second-hand motor vehicle market where buyers are unable to distinguish between good cars and bad ones – lemons. The result is that buyers presume that all second hand cars are bad and prices are driven down as a result. The effect is that sellers of good cars do not get a good deal and good cars are driven out (excuse the pun) of the market by the bad cars. The problem has several solutions. The two most important are relevant here. The first is to ensure that, by means of regulation, full and necessary information is provided by businesses to investors to enable them to distinguish between good and bad investments. Hence the need for accounting, the regulation of accounting, and auditors. The second relates to the creation of a demand for information intermediaries, such as financial analysts and credit rating agencies who are expert in interpreting business information and are judged on the independence and quality of their assessments. As we will see in later chapters, whilst both solutions help to resolve the essential problem, they bring with them their own problems.

Market abuse

Market abuse is a general term to describe actions by investors that unfairly take advantage of other investors. It includes not only insider dealing but various actions attempting to m...