![]()

Part I

![]()

Chapter 1

Second Life

Your world, your imagination

I like to think, (it has to be!), of a cybernetic ecology, where we are free of our labors, and joined back to nature, returned to our mammal brothers and sisters, and all watched over, by machines of loving grace.

Richard Brautigan1

To contextualize Cyber Zen’s investigation, this chapter analyzes Second Life’s media practices. I logged on to Second Life on December 12, 2009, after a Gmail “ping” pulled my attention out of the Microsoft Word document from which this very text would eventually evolve. Just a few minutes before, in an attempt to reboot my lagging fieldwork, I had contacted the resident Mystic Moon about a possible interview.2 The ping marked the arrival of Mystic’s positive answer and disentangled my awareness from my computer screen. I became conscious of my office’s background noise: the jazz pianist Cedar Walton playing on my earbuds, the minor cord humming of the furnace, the large black cat in my lap, and a slight trembling from the train rattling by a half block away. In real life, Mystic was a twenty-six-year-old German who was finishing up his apprenticeship as a digital designer. In Second Life, Mystic was already a well-recognized builder, who had created the Buddhist garden of Gekkou, one of the most stunningly beautiful sims in Second Life.3

Second Life is a virtual world, a type of digital media practice that differs from other forms because it is a shared immersive cyber-social environment. In our interview, Mystic described Second Life as a “sim[ulation], or a multi-user platform such as World of Warcraft in which you take on an assumed persona and interact with other players.” Second Life differs from flat digital media, such as the World Wide Web and email, because of a high rate of “immersion,” which describes the feeling of “being in” a virtual world that occurs when a user’s awareness no longer focuses on real life but has moved inworld. Many forms of media, from books to cinema, are immersive. Users often lose themselves in the narratives that media practices construct. Digital virtual worlds differ, however, because users share their immersion with others. As Mystic’s partner, Fae Eden, who had come with him for the interview, added, “Second Life is a world because there are people.”

The email message sent on December 12, 2009, contained a SLurl, a hyper-link, to Mystic Moon’s location. By clicking the SLurl, I opened Second Life, a 3D graphic virtual world housed in cyberspace that users are able to access from any networked computer on the globe. Clicking the SLurl link opened a page in my web browser FireFox, which displayed on my computer’s desktop a world map of Second Life centered on the region, or sim, of Gekkou.4 While not actual, Gekkou was a “conventional reality,” a term, which we detail in Cyber Zen’s conclusion, that describes mutually constituted and historically contextualized material discourses, practices, and objects by which people construct, interpret, and manage their everyday lives. As a conventional reality, virtual worlds indicate neither the natural world nor the solipsistic creation of an individual. Rather, they are a social reality conditioned through the repetition of public performative acts that create persistent lived worlds.

Once just the fantasy of science fiction writers and computer hackers, by the time of our study in 2008, popular culture had been seduced by the geeky siren call of virtual worlds. As Philip Rosedale, the founder and first CEO of Linden Lab, Second Life’s corporate owner, prophesied in a May 16, 2007, interview in The Guardian, “Today Second Life, Tomorrow the World… This is only the beginning of the 3D web.” While Rosedale’s prediction has proven hubris-tic, virtual worlds and virtual realities continue to hold a clear presence in the popular imagination. Yet, what makes Second Life a social space perceived to be distinct from real life? If one leans back from the keyboard it is not immediately clear how the pixels and sounds that compose Second Life are any different from other types of digital media, such as websites, social media, and digital games. In all cases users never leave their chair. On the thin level of description, Second Life consists of merely moving pixels around on the screen through keystrokes and mouse clicks. As an interface, Second Life consists of programmable bits manipulated through the use of graphical user interfaces (GUI) as well as Windows, Icons, Menus, and Pointing devices (WIMP).

This chapter argues that residents’ fantasies transform the pixels on the screen into a lived world. As the game researcher Richard Bartle writes, “virtual worlds are the places where the imaginary meets the real.” Linden Lab’s web-page, “What Is Second Life?,” styles the platform as “a virtual world – a 3D online persistent space totally created and evolved by its users. Within this vast and rapidly expanding place, you can do, create or become just about anything you can imagine.” When I asked the resident Algama GossipGirl why she used Second Life, she laughed and answered, “the world fascinates me.” When I asked her why, she replied, “I can live out my fantasy.” Often users’ fascination with virtual worlds is assumed to stem from the digital media themselves or to boil up from the innate human desire to create ordered worlds of meaning. Rather than approaching virtual worlds as determined by digital media or by some innate human quality, this chapter describes the complexities of this early twenty-first-century everyday media practice in order to foreground human agency and historical context.5

To investigate how the virtual world’s media practices transform the empty pixels on the screen into fantastic lived reality, we refract our analysis through Second Life’s tagline, “Your World, Your Imagination.” Taglines, like capitalistic catechisms, are statements made by a corporation that provide a concise explanation of what it offers. “World” refers to immersive screening practices, which are enabled by digital affordances and virtual world properties that are indebted to the history of the concept of cyberspace. “Imagination” describes the platform’s creative software tools that enable resident fantasies, which are vital because they suture users into the virtual world. Second Life’s use of the imagination emerges from a “digital utopianism” that arose in the 1970s from the unlikely marriage of computers and the 1960s counterculture. The “your” displays the tension between the promise of unlimited imagination and alienating Network Consumer Society, the cultural system that arose in the last quarter of the twentieth century, based on the desire to purchase goods and services, which do not merely fulfill biological needs but cater to consumer fantasy.

Since I ended our fieldwork in 2011, the appeal of digital media has not weakened and has if anything grown stronger. While Second Life will never become the cyber-frontier that early boosters predicted, because of how it engages the imagination, society will continue to be haunted by the specter of the virtual.6 The chapter adds to our understanding of the culture and society of virtual worlds, particularly massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG), a genre of role-playing platforms in which a very large number of users interact with one another within a game setting. Also, by analyzing the part digital Zen plays in the construction of virtual worlds, this chapter lays the foundation that allows one to better diagnose the role religion plays more generally in emergent media. As the pioneer in the study of digital religion Lorne Dawson writes, “the lure of cyberspace remains strong and it is unlikely that the cultural, social, and psychological consequences of the Internet for religion can be avoided or reversed.”7

World

The “world” in Second Life’s tagline indicates the creation of an alternative conventional lived reality through immersive digital media practices, which are contextualized in the techno-fantasy of digital utopianism. The Second Life platform can be traced back to 1999 when the American entrepreneur Philip Rosedale founded Linden Lab, a privately held American Internet company.8 In its alpha stage, called Linden World, the platform was not open to the public and was basically a primitive shooter game. The Second Life platform was publicly launched on June 23, 2003, and over the next few years there was a slow but steady growth in the number of users, and features such as teleporting and the inworld currency the Linden were added. Second Life caught the attention of popular culture when, on May 1, 2006, the resident Anshe Chung was featured on the cover of BusinessWorld and reported to be the first person to become a real-life millionaire due to a Second Life business. Chung’s story brought a flood of media coverage and pitched the population growth further, and on October 18, 2006, the millionth resident joined.9 In the mid-2000s, the platform was the darling of the press, with the American author Kurt Vonnegut’s inworld interview, a congressional meeting on virtual worlds and terrorism, and of course the now infamous appearances on the NBC comedy The Office and Comedy Central’s The Daily Show.10 The honeymoon soon faded, and both critics and residents have been tolling the virtual world’s death knells ever since. Second Life may have lost its luster. Still, outside the media hype, Second Life slouches along. As of April 2, 2014, there have been over thirty-seven million signups for Second Life, with a least one million users logging on every month and approximately 60,000 users logged on at any one time.11

Second Life’s digital affordances and virtual world properties

When a virtual world is effective, however, users’ awareness is organized in such a way that they communicate as if they are present in another place. As I typed on my computer, I was no longer just in my office but also aware of being in the region of Gekkou, if only virtually. Residents often talked about “falling” into Second Life, of being immersed and enveloped by the virtual world. Richard Bartle, in Designing Virtual Worlds, writes, “People want to be immersed. Designers want them to be immersed.”12 Yet how is this done? Second Life is not “virtual reality,” which describes computer-modeled environments that simulate haptic physical presence using multimodal devices such as goggles, gloves, and treadmills. Rather Second Life is a “virtual world” in which users play a role and interact through their onscreen representations. Even while they danced or prayed, shopped or engaged in edgeplay, residents were never ignorant that Second Life was ultimately just pixels on a screen.

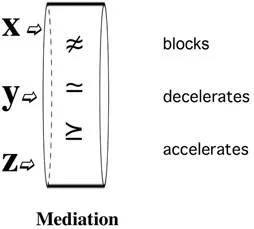

Second Life’s digital practices immerse users through digital affordances that generate the properties of virtual worlds. “Affordance” refers to the properties that shape how an object can be used and can either block, increase, or decrease a particular action (Figure 1.1). For instance, a doorknob affords the opening of a door and the handle on a mug of coffee affords its consumption. One could force a door by kicking, but using the knob affords its smooth release, and one could drink the coffee without using the handle, but the grip affords its consumption without burning one’s hands. Different media have differing affordances. Second Life is a “digital media practice,” which, as opposed to “analog media” such as newspapers, film, and vinyl discs, consists of electronic technologies that are handled by computers as a series of numeric data. All digital media technologies are composed of programmable bits that can be used for semiotic manipulation and thus share common affordances. “Bit,” a portmanteau of “binary” and “digit,” is the basic unit of computer-assisted communication. Unlike analog media, which use a physical property of the medium to convey the signal’s information (think of the needle on a vinyl record), digital media consist of digital bits, like a row of on/off switches, which can have only one of two values, most commonly represented as “0” and “1.”13

Figure 1.1 Affordances. The properties that shape how a medium either blocks, increases, or dec...