![]()

1

Introduction

Defining Community-Built

Barry L. Stiefel, Kristin Faurest, and Katherine Melcher

Throughout history and around the world, community members have come together to build places, be it rural farmers raising a barn in North America, Malian villagers holding a festival to re-plaster their adobe mosque, or neighbors in New York City’s Lower East Side turning vacant lots into a community garden. What all these places have in common is that they are community-built; they “meet a set of criteria that stress participation and result in an environmental change” (Delgado 2000, 76); they bring community members together to construct projects in public and semi-public spaces.

The concept of community-built is deeply embedded within the world’s heritage. Historically, community-built works can be found in the civilizations of both nomadic and sedentary peoples. One of the earliest recorded instances of a community-built project is found within the Hebrew Bible, concerning the creation of the Tabernacle, the transportable house of worship that the ancient Israelites used during their wanderings in the wilderness: “Every man whose heart inspired him came; and everyone whose spirit motivated him brought the portion of God for the work of the Tent of Meeting [Tabernacle], for all its labor and for the sacred vestments” (Exodus 35:21).

The contemporary American practice of community-built emerged in the 1960s, with activists such as Karl Linn and Paul Hogan building common spaces and playgrounds in inner-city Philadelphia; Lilli Ann Rosenberg creating murals with children in Harlem housing projects; and Bob Leathers working with parents to construct playgrounds in upstate New York. These individuals, along with other artists and designers, formed the Community Built Association (CBA) in 1989. The CBA defines community-built as a “collaboration between professionals and community volunteers to design, organize and create community projects that reshape public spaces. Projects accomplished through community initiative and professional guidance include murals, playgrounds, parks, public gardens, sculptures and historic restorations” (Community Built Association 2014).

Figure 1.1 Barn raising, farm of Joseph Bales, Lansing, North York, Canada, circa 1900–1919

Figure 1.2 Community members refinishing a mud plaster floor, Togo, 1996

Today, community-built spaces, artworks, and other elements can be found in almost every community around the globe. For example, school murals across the United States connect youth with their heritage and local history. Community gardens in places as diverse as Budapest, Hungary, and Roanoke, Virginia, engage both neighborhood residents and university design students. In Pennsylvania, volunteer-driven sidewalk and facade improvements are intended to revive small-town main streets.

Figure 1.3 Community garden in Berkeley, California, 2008

Figure 1.4 A community-built park in New Orleans, Louisiana, 2010

Despite its widespread existence, most community-built work is rarely classified as such, perhaps because of its grassroots and multi-disciplinary nature. Beyond Melvin Delgado’s (2000) book, Community Social Work Practice in an Urban Context, little research about community-built practices as a whole exists. Multiple case studies focus on one realized work or practitioner (see, for example, Rofe 1998; Semenza 2003; Hutzel 2007; Semenza and March 2009), and other research investigates one type of project—for example, playgrounds (Daniels and Johnson 2009; Wilson, Marshall, and Iserhott 2011), murals and community art (Delgado 2003; Rossetto 2012), or community open spaces and gardens (Francis, Cashdan, and Paxson 1984; Hou, Johnson, and Lawson 2009; Draper and Freedman 2010). Most of this research and writing remains within their specific disciplinary boundaries, failing to draw connections across the spectrum of community-built projects. As far as the editors of this volume are aware, this is the first interdisciplinary volume to analyze the concept of community-built across the fields of urban design, historic preservation, and community art. This volume brings together research into a variety of community-built practices in order to explore their commonalities, while at the same time describing community-built in the broadest sense.

The quest to expand the concept of community-built beyond the work of Community Built Association members resulted in the call for contributions that formed this book. In the responses, we found a diversity of projects that include local people in the construction and preservation of community places. This book contains examples of community-built projects from the United States, Canada, and Europe; these include art projects, gardens, streetscapes, and buildings. The projects included celebrate the small and the specific, the often immeasurable yet meaningful. However, taken as a whole, they illustrate a cross-disciplinary approach to community development and placemaking. They provide a powerful illustration of how local engagement with built projects can strengthen communities.

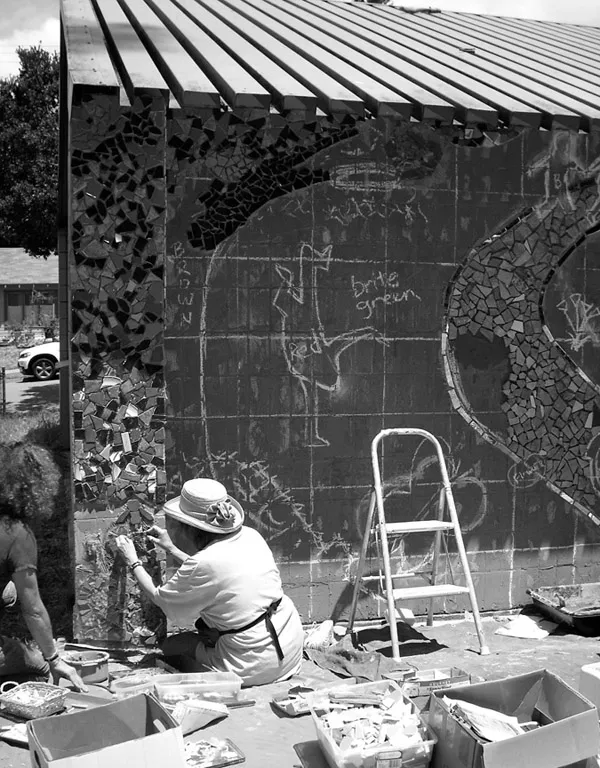

Figure 1.5 A community-built mural under construction at Maxwell Park, Oakland, California, 2008

Figure 1.6 A community-built playground under construction in a village in Thailand, 2006

The Trans-Disciplinary Nature of Community-Built

The contributors to this book come from three primary disciplines: urban design, historic preservation, and the visual arts. Despite this, all of their community-built examples can also be classified as a form of asset-based community development: “a planned effort to build assets that increase the capacity of residents to improve their quality of life” (Green and Haines 2008, 7). Like other community development initiatives, community-built projects emphasize the use of local resources and community-controlled, collaborative decision-making. Each of the three primary disciplines has a subdiscipline that utilizes an asset-based approach: community design and placemaking within urban design, community-based historic preservation within historic preservation, and community arts within the visual arts. The following is a brief overview of these subdisciplines and how community-built projects can be categorized within them.

Community Design and Placemaking

Community design is “based on the principle that the environment works better if the people affected by its changes are actively involved in its creation and management instead of being treated as passive consumers” (Sanoff 2000, x). In the 1960s, in reaction against the U.S. government urban renewal program’s displacement of minorities, community design proponents advocated for involving local residents in the design decision-making that impacted their neighborhoods (Hester Jr. 1989; Toker 2007). Today, at least within the United States, local involvement in public design projects is often mandated; and terms such as public interest design and social impact design are used more frequently to describe design processes that focus on social concerns. Additionally, terms such as DIY urbanism and tactical urbanism describe small-scale community design projects that can be easily implemented with or without government support (Iveson 2013; Pagano 2013; Lydon and Garcia 2015).

Placemaking, a term that describes a specific approach to spatial design, incorporates much of community design’s philosophy and applies it specifically to the public realm. In placemaking, a public space’s design is driven not by designers or decision makers, but by the local community’s assets, identity, character, and needs (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Urban Studies and Planning 2013). Placemaking takes a trans-disciplinary approach to public space design: the benefits of a community space are not just limited to the provision of recreation and the contribution to urban ecology but instead viewed as a complex web that encompasses other factors such as public health, social capital, climate change amelioration, and economic well-being.

Within urban design and placemaking, more attention is being focused on small-scale community projects and their ability to impact larger issues such as neighborhood cohesion, crime, public health, and socioeconomic mobility. This isn’t a completely new paradigm: back in the 1960s, Jane Jacobs (1992) pointed out the importance of vibrant, lively sidewalks and the contributions of small stores and other community institutions to make our cities safe, happy, equitable places. During that same period, urban planner Oscar Newman’s (1976) defensible spaces approach in subsidized housing developments demonstrated that when we give people the power and the responsibility to change their communities on a manageable scale, they respond by taking charge. Collective efficacy—people’s willingness to help each other out, to connect, to make an effort—increases, and the sense of helplessness and apathy that can so often be the product of life in government-owned housing decreases. When people are given the opportunity to shape their environment in a way that makes their surroundings more comfortable, more colorful, or more personalized, they feel a greater power to make other changes as well. They also have an enhanced sense of stewardship and a closer relationship with the friends and neighbors who helped them realize the project.

From the general concept of placemaking, more specific categories have emerged: tactical placemaking, using small-scale, incremental improvements to help stimulate larger-scale positive change; strategic placemaking, a targeted process that uses activities and projects to attract talented workers to a place; and creative placemaking, which is based upon using visual arts and cultural activities to shape a place (Wycoff 2014).

In placemaking, the opinions and preferences of the future users inform the design of the place, which strengthens stewardship. The mutual stewardship of place and community sets up a symbiotic relationship in which communities transform places and the places continue to transform communities. Community designers observed this symbiosis as well; they found that places designed with community participation experience more use and less vandalism (Francis 1983). These designers believe that by being involved in the design process, participants can develop a sense of pride and an attachment to the place (Hester Jr. 1989; Sanoff 2008).

Community-built projects—because they often take place in small-scale, semi-public places—fit well within the placemaking paradigm. They often come to fruition in what might be considered a third category of public space: neither private nor public, but semi-public (for example, community gardens or other shared spaces). At the same time, community-built projects remain distinct within the field of placemaking because of their emphasis on community involvement in the construction phase of the project.

Within this volume, we have five chapters that highlight community involvement in the building of public and semi-public places. Kristin Faurest, in Chapter 3, “Kalaka: Four Stories about Community Building in a New Democracy,” discusses a variety of neighborhood projects within Hungary, including a school fruit orchard, community courtyard gardens, and a re-imagined public space. In Chapter 4, “Reflections on Community Engagement: Making Meaning of Experience,” Terry L. Clements and C. L. Bohannon share their experience with similar projects—a community park, bus stop, and community garden—in a very different context, the Hurt Park neighborhood of Roanoke, Virginia. Barry L. Stiefel’s “Community Eruvin: Architecture for Semi-public/private Neighborhood Space” (Chapter 6) describes a unique form of shared community space: eruvin, physio-psychological enclosures used by halachic-observing1 Jews that enable them to “carry” in the public domain on their Sabbath. Daniela Patti and Levente Polyak, in Chapter 10, “Building Informal Infrastructure: Architects in Support of Bottom-Up Community Services and Social Solidarity in Budapest,” explore adaptive reuse of a public park and waterfront in Budapest. In Chapter 12, “Building Streets and Building Community,” Katherine Melcher shares three examples of community-built streetscapes in the United States.

Community-Based Historic Preservation

In most countries, historic preservation (often called heritage conservation outside of the United States) is a top-down initiative from the national or regional government. However, within the United States, the historic preservation movement began as a grassroots, community-based endeavor. For instance, in 1816, due to public outcry by the citizens of Philadelphia, the city purchased Independence Hall (then called the State House) from the State of Pennsylvania, which had plans to demolish it. Again, in 1853–58, under the leadership of Ann Pamela Cunningham, women across the United States came together to save Mount Vernon, George Washington’s plantation estate in Virginia, from neglect and proposed redevelopment.

While separated by more than a century from these earliest preservation-related achievements, the contemporary American practices of historic preservation also emerged in the 1960s, most significantly related to the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. Specifically, within the act, Congress specified in Section 101(4) that “the Secretary [of the Interior] may accept a nomination directly from any person … for inclusion of a property on the National Register,” (National Historic Preservation Act 1966) whereas before for National Historic Monuments or National Historic Sites, only the president and the secretary of the interior had the specific authority to nominate a place nationally historic. So, besides the physical maintenance or repair of historic places, the designation and heritage interpretation of them is frequently a community undertaking, and often initiated at ...