This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Exploring the consequences of federal devolution on state budgets, this work deals with three major areas of concern: the effect of moving large numbers of welfare recipients into labour markets; the planned federal reforms in the health care field; and trends in federal aid.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The End of Welfare? by Max B. Sawicky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

ONE

The New American Devolution

Problems and Prospects

Introduction

Like the weather, federalism is something people talked about for years but did nothing about. That all changed with the 104th Congress of 1995–96, which launched a more earnest push than previous advocates of new federalism for devolution of the public sector—shifting taxing and spending responsibilities from the federal government to the states.

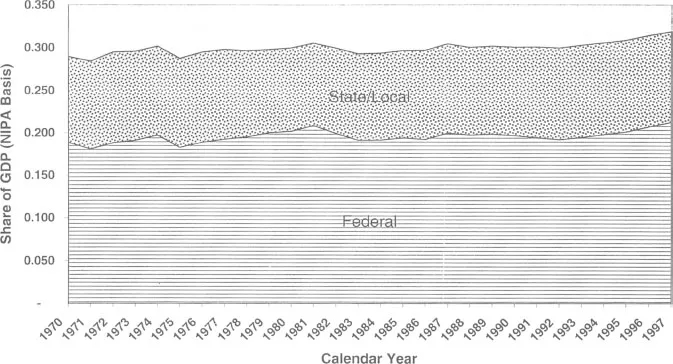

Prior to 1995, state and local governments had already grown significantly. Figure 1.1 depicts the trend in receipts by level of government, as a share of the economy as a whole. It is interesting to note that contrary to concerns about “tax competition” for increasingly footloose taxpayers in a globalizing economy, revenues have seen increases since 1980. As John Shannon has pointed out, there has been no meltdown in state and local governments’ command over taxable resources.

On the expenditure side, in one important sense, the states are already more prominent than the federal government. The vast bulk of federal expenditures—68 percent in 1997—is devoted to Social Security/Medicare, defense spending, and net interest outlays. Correspondingly, much of what we normally associate with the term “government,” in view of services directly provided to the public at large by government employees, is under the purview of the states.

If we exclude Social Security, Medicare, net interest on the federal debt, and defense from the total expenditures of federal, state, and local governments in the United States, 80 percent of what remains is administered by state and local governments. In addition, most public investment (infrastructure, education, and training) is financed by state governments, and most infrastructure facilities “reside” in the states.

Figure 1.1 Trends in Public Revenues

Therefore, it could be said that the bulk of national domestic policy is already decentralized or “devolved,” after recognizing the federal spending on transfer payments and grants-in-aid where disposition is controlled by the recipient families and subfederal governments. Accordingly, one may ask how much more privatization or devolution is conceivable in the most fundamental respects.

The 104th Congress answered in two basic ways. First and foremost, under the rubric of welfare reform it replaced the unpopular Aid to Families with Dependent Children with a new program known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). TANF vests substantially increased discretion in state governments for providing public assistance.

Second, the Congress addressed a long-standing complaint of state and local governments: the promulgation of legislation, regulations, and judicial decisions that are binding on said governments, known generically as “mandates.” Under the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act, legislation that includes new mandates is subject to comprehensive cost impact analysis before proceeding to final consideration by Congress.

A less direct, more long-standing policy with devolutionary implications was the plan to balance the federal budget forged between the 105th Congress and President Clinton. Included in budget law is a freeze on spending for federal domestic discretionary programs. The freeze is stipulated in terms of a fixed dollar “cap” which is not adjusted for inflation. The implication is that spending of this type must decrease in real terms and as a share of the economy.

It turns out that almost all grants-in-aid to state and local governments, with the exception of the Medicaid program, fall into the category of capped expenditures, so budget balancing rules entail an erosion of aid to governments. Unlike Medicaid funds, whose use is specified in federal law, state and local governments have significant discretion over the use of other grants-in-aid. Any reduction in such funds implies another de facto transfer of policy initiative from the federal government to the states.

The extent of scheduled cuts in the 1997 budget deal was about $65 billion, after adjusting for inflation. One corollary of these cuts is a projected decline in public investment—spending on infrastructure, education and training, and research and development (GAO 1998). The 1997 deal was not unique in this regard. Deficit politics and budget rules conspired throughout the 1980s to squeeze domestic discretionary spending, grants-in-aid (Kenyon 1992), and public investment (Sawicky 1992). Increases in Medicaid grants could have been only partial recompense, given the restrictions on the use of such funds.

The advances in devolution have been legislated under the umbrella of a relatively long economic recovery marked by record lows in unemployment. All revolutions should enjoy such fair weather. In less happy economic times, the new extent of decentralization in the U.S. public sector could cause some important pressure points to blow their gaskets, so to speak.

The leading concern is the effect of moving large numbers of welfare recipients into labor markets (Bernstein 1998), since unemployment will probably not remain low indefinitely. More ominous than the dim opportunities foreseeable in the low-wage labor market are the alarming dips in participation in the Food Stamp Program and Medicaid after 1996 (USDA 1999; HCFA 1999). These reductions exceed those that could be attributed to the economic recovery (Primus 1999). In some way, the reform of welfare may have occasioned a more widespread pruning of enrollment in a variety of aid programs and increased poverty. There is some doubt that state governments would be able to finance welfare needs under the new system in the teeth of a real economic downturn. There are also questions as to the states’ ability to cope with the social consequences of large numbers of recipients hitting the time limits and being rendered ineligible for assistance. Another source of anxiety is fear that economic changes raise the pitch of competition between state and local governments for tax bases, and conversely encourage an unseemly contest to repel or expel those perceived to bring net financial burdens to the public sector.

A second set of difficulties pertains to prospective changes in health care. To some extent, federal reforms in health care will shift costs to the state-local sector. One possibility is that voters will look to the states for services that the federal government no longer provides or subsidizes to the same extent. The leading case in point would be a change in the status of nursing home residents now supported by federal programs. A second is that expansion of Medicaid eligibility brings automatic state matching requirements. A third is that a federal squeeze on Medicare providers in the form of reduced payments could drive beneficiaries into the Medicaid program and increase the states’ fiscal burden.

The third area of difficulty is the trend in federal aid. While cuts in the past have been substantially replaced with state revenues, this may not continue indefinitely. Moreover, the costs of cuts may be less apparent because they facilitated deferral or neglect of public investment priorities, particularly in infrastructure and education.

State and local governments have been forced into ever-increasing self-reliance for some time. Since 1981, there has been a dearth of lasting federal initiatives in domestic policy. Some of the few exceptions have increased the states’ financial responsibilities, including new mandates and expansion of Medicaid eligibility (Kenyon 1992; Conlan 1986).

This book offers research that bears on new and incipient pressure points. It evaluates some ways of coping at the state level, and suggests some approaches to recasting federal policy.

This book makes two types of contributions. The first addresses background topics in state fiscal policy. Devolution is an inescapable feature of this setting, but it is not the only one. Trends that predate the current policy regime, such as the erosion of aid to governments, obviously inform present circumstances, including the fate of devolution itself.

The second entails three missions that state and local governments pursue by means of expenditure programs. In some cases, these missions have been directly expanded by devolutionary measures, the primary example being welfare reform. In others, the halt of federal initiatives or the erosion of grants-in-aid puts a new premium on self-reliance. In either case, there will be consequences for the nation that spill over state boundaries, beyond the reach of individual state governments. These studies provide some guidance in areas where a resumption of federal initiative may be appropriate.

In summary, this book offers new insights and findings on the setting in which devolution has begun, the fiscal ramifications of these developments, and a sample of policy recommendations. To be sure, there are many miles yet to be traveled in this journey. Hopefully, this volume will provide the reader with a map of where we’ve been and where, given the natural limitations of foresight, we may be headed.

The Setting for State Policy

The book begins with studies of the economic and political background for public policy in the states. Timothy Conlan and James Riggle discuss the changed administrative and political nature of state governments. Steven Gold and Bruce Wallin discuss the fiscal environment. Daphne Kenyon evaluates the strength of state revenue systems. Timothy Bartik analyzes the effects of tax competition on state economies. Joseph Persky and Wim Wiewel describe basic tensions arising from the political separation and economic integration of city and suburb that are increasingly a concern of state policymaking.

The Political Environment

Conlan and Riggle open with an optimistic survey of improvements in state government administrative capacity, political responsiveness, and policy initiative over the past fifty years. Their conclusion is that while constraints on policy activism in the states are inescapable, conditions for greater activism have changed decisively for the better.

They begin by reviewing the fundamentally restrictive “ground rules” of our federal system, ordained by our Constitution and our political tradition of classic liberalism. Before the rise of national government, these rules made for a narrow view of public responsibilities, epitomized by such phrases as “the night watchman state.” This ice was broken decisively by the economic crisis of the 1930s and national security concerns after World War II, leading to a steady growth in the federal government and the U.S. public sector as a whole. The spectacle of a dynamic, expanding national government reinforced the image of a benighted state government.

In contrast to the popular ideology of limited government, Conlan and Riggle cite evidence of widespread “operational liberalism,” which means that in specific practical cases, such as transportation or environmental cleanup, there is broad public support for government activism. Perhaps paradoxically, activism by a handful of states in limited areas has given rise to major, national generalizations of such efforts. The best example is state-based social insurance being succeeded by the national Social Security system.

It could be argued that the diversity of states generates isolated, intense commitments of public effort that stand a chance of catching fire at the national level, if only they are first allowed to emerge in a relatively pristine form in individual states. The “laboratory of federalism” may also be something of a “hothouse”; new policies can germinate in environments that are more conducive to innovation than the national government. As Richard P. Nathan (1990) has suggested, a time of federal retrenchment can also be a time for state activism.

Against the flexible pragmatism of public opinion regarding proper roles for government, Conlan and Riggle raise a few warning flags. One is planted in economic realities that may constrain state initiatives in certain areas, particularly income redistribution. A second pertains to periodically low public interest in state and local government activities.

The Depression cemented an image of state governments as mean and incompetent. They failed to grant full political rights to minorities, and they were economically and administratively incapable of performing basic tasks. Conlan and Riggle trace the progress of the states from their nadir. One thread is the growth of state government power, in the form of strengthened gubernatorial prerogatives, more rational organization of functions, and some advance in respect of ethical considerations. A second is the expansion of state revenue systems relative to the size of the economy and compared to the federal government since 1950 (and even since 1980). A third is the spread of the political franchise to excluded minorities, the intensification of interparty competition, the decline of single-interest groups’ domination of specific states, and improved apportionment of legislative representation.

President Clinton has famously remarked that “the era of big government is over,” but it may only be that we are witnessing a passing of the baton of public activism to the states. As noted above, state and local spending has been growing and may advance even more in the wake of such federal devolution measures as welfare reform.

Conlan and Riggle sketch two contrasting scenarios for the future. Under one, the fever to cut taxes and spending cascades from the national government to the states, driven in significant part by the devolution of public assistance. Welfare reform and tax competition could lead to a “race to the bottom” (Peterson 1990) in benefit standards and public spending in general. The Republican realignment could become permanent and lead to lasting reductions in the size of government at all levels.

The natural makeup of U.S. federalism, on the other hand, could function as a “shock absorber” and dilute a national devolutionary impulse. Federalism disperses power and slows the march of all manner of ideological crusades. In policy, as in war, it may be easier to play defense than offense. The legacy of the New Deal and Great Society may prove capable of withstanding threats from devolution. Newly enfranchised groups will not easily surrender their basic rights, and new interest groups will not neglect their well-being.

On the whole, Conlan and Riggle show that policymaking in the states will not be easy to predict. Evidence for a new activism is no less forthcoming than the prospects for a contraction of the U.S. public sector at all levels.

The Fiscal Outlook

Before his untimely death, Steven Gold submitted a first draft to the project from which this collection originated. Bruce Wallin has revised and updated Gold’s draft for presentation here.

Gold and Wallin foresee profound implications for the states arising from the decisions made by the 104th Congress. Along with external factors, these decisions point to projected “structural deficits” in the states’ futures, which means that under the maintenance of current policies, state government budgets will run short of tax revenue and be obliged either to reduce spending or to increase taxes.

The most familiar factor in national policy has been the slow-motion decline in federal aid to state and local governments since 1978 (excluding Medicaid), given the imperatives to balance the federal budget and to implement the cost-cutting measures in the Medicaid program noted earlier.

Alongside the projected further declines in federal aid is the welfare reform measure passed in 1996. Changing AFDC to a block grant means that aid will not be as responsive to changing economic conditions. A “rainy-day” fund was provided for by the reform, but as Chernick and Reschovsky show in their contribution to this volume, the fund is highly unlikely to be adequate in a recession.

Gold and Wallin explore the role of external factors that are independent of national policy. One is the projected decline in economic growth. Another set consists of demographic trends that are expected to increase the need for public school expenditures, higher education, and Medicaid. A third is the rapid rise in correction costs, in the wake of new state policies on sentencing convicted criminals.

Gold and Wallin find public opinion much the same as Conlan and Riggle. “Operational liberalism” is borne out in a lack of demand for major spending reductions. As noted above and shown in Figure 1.1, total state-local spending has not declined since 1980. To some extent, such spending is propped up by federal mandates (Kenyon 1992).

In the face of incipient spending pressures, the authors suspect that existing revenue systems are inadequate. This topic is taken up in greater detail in Kenyon’s contribution, discussed below. State income tax revenues keep up with economic growth, by and large, but they contribute only 30 to 40 percent of state revenue. Moreover, recent changes in some states have rendered income taxes less “elastic” with respect to the economy, which means revenues fail to keep pace with economic growth. Other state revenue sources are “inelastic” for other reasons.

Gold and Wallin note that in boom times, budget surpluses are generated and politically popular tax cuts are possible. The real test of state revenue systems is imposed only over the course of an entire business cycle. It is too soon to predict whether states will try to recoup revenues in the next recession or choose to cut services instead.

Against this background, the authors address the principal questions surrounding devolution. The largest one—health care—is also one of the least clear, given the uncertainty about the rate of growth of costs and effects of fed...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The New American Devolution: Problems and Prospects

- 2. New Opportunities/Nagging Questions: The Politics of State Policymaking in the 1990s

- 3. The State Fiscal Predicament under the New Federalism

- 4. How Strong Are State Revenue Systems?

- 5. Growing State Economies: How Taxes and Public Services Affect Private-Sector Performance

- 6. Economic Development and Metropolitan Sprawl: Changing Who Pays and Who Benefits

- 7. State Fiscal Responses to Block Grants: Will the Social Safety Net Survive?

- 8. Fiscal Disparities and Education Finance

- 9. Revenue Sharing as a Public Investment: Why Unrestricted Aid to Local Governments Will Stimulate Municipal Capital Expenditures

- Appendix: Population, Income, Poverty, and Standardized Fiscal Health (1990)

- Index

- About the Authors

- About EPI