![]()

Part 1

From Research to Implications

A. Introduction

Whatever the reason you go into teaching—whether it is for love of the subject, because of family tradition, the intercultural contact with students, the wish to make a difference, or the job security—and regardless of whether you aim to stay in teaching for a short time before doing something else, or you regard teaching as a calling or a plan for life, things happen to refine and even change those hopes and aims. Some of us will leave after a while to pursue other career paths; others may be promoted out of the classroom or burn out on the job; and others will, sometimes to their own surprise, stay on … and on.

It may seem to the individual teacher that the reasons for staying or leaving are personal ones. You might explain it to yourself (and others) as due to a family or health situation, or because of changes where you work, or because you realise you have chosen the wrong job or have had to cope with too many changes and reforms. Alternatively, you might find that you love working with young learners or developing new materials and skills. While recognising these circumstances (as well as the multitude of others not mentioned here), we three authors believe that those initial motives for entering English language teaching do evolve, and the possibility for learning as a teacher in the different contexts in which you work shapes your professional life, and it can often influence whether you end up staying or leaving teaching.

We include within teacher learning both the preparation, initial training, and on-the-job support some new teachers receive as they start their careers and also the gradual development of knowledge, attitudes, and skills that happens over time as you teach your way through the years. Teacher learning is an important factor in turning what can seem, at various points in your career, a stressful, overly routinised, day job into a varied, stimulating, renewing, and satisfying form of on-going work. As one of the researchers we include in Part 1, Michael Huberman (1991), observed, “the vast majority of teachers [in his study] express an authentic enthusiasm for their own personal and professional development, which, they feel, has sustained them over the years” (p. 180).

All three of the authors trained as language teachers and have worked in classrooms as language teachers and teacher educators for many years. We have worked with those preparing to become teachers on initial teacher training and with those who are teaching through further teacher education courses. We have been sustained throughout our work by our own personal and professional learning, which has been our ‘development over time’. Thus, when thinking about how to approach teacher development for this book, our own longevity in the field suggested we pursue it from the vantage point of time. In this book, we would like to share with you some of what we have learned from research and from our own practice.

Choosing Research That Is ‘From—Not About—Teachers’

As we reviewed the major research that relates to the theme of this book, teacher development over time, we realised that two dimensions needed to inform our decisions about what to include in Part 1. Clearly the content is centrally important—the research we selected frames the issues we want to discuss and anchors those issues in careful study of teachers’ experiences. However, we were also concerned that the work we chose would represent teachers’ professional lives from their own points of view. In other words, the research we included comes from the work that teachers do; it is not simply an external view about teachers’ work. This orientation—that we wanted studies which described teachers’ own views of how their work develops through a professional lifespan—is what we mean by the phrase, choosing research that is ‘from—not about—teachers’. In terms of research methodology, we wanted to use studies that documented teachers’ own views of their development over time. These are studies that seek to understand teaching from teachers’ perspectives, from an ‘emic’ or insider’s view.

Three Researchers Who Have Studied the Trajectories of Teacher Development

We selected three researchers—Dan Lortie, Michael Huberman, and Amy Tsui—who met these criteria. We refer to them as ‘trajectorists’ because they each have studied the arc of teachers’ understandings of their work over time. The patterns and trajectories these researchers have identified can offer insights into teacher development. We explain a bit about each of them below.

Dan Lortie, a sociologist from the University of Chicago, was one of the first researchers in the early 1970s to conduct a large-scale study of teachers’ experiences (Lortie, 1975). His is the first research discussed in this section. Michael Huberman, whose work is the second reported in this section (Huberman, 1989), is a Swiss-American researcher who followed on Lortie’s impulses in many senses by examining the experiences of Swiss secondary-school teachers to identify possible patterns in how they experience teaching over time. Both Lortie’s and Huberman’s work could be considered groundbreaking, both in the content of their studies and in the ways in which these studies were conducted. Their work led to broad areas of research into how the conditions of teaching shape teacher learning, and how that learning can be characterised over time. The third researcher, Amy B. M. Tsui, represents a different strand. In this section, we draw on her outstanding synthesis of research on expertise and teaching knowledge (Tsui, 2003). In her study, she brings together an impressive amount of research in a coherent way, challenges some of its basic tenets, and uses the data from her study of four teachers to create a clear conceptual model of how expertise develops.

In selecting these researchers, we decided to draw on our different perspectives and to write about them in our individual styles. We hope that you will find it engaging (and not simply a bumpy read). We wanted to remind you, as reader, of our different voices and points of view. We start by explaining what interested us about each of the researchers and why we chose them.

Donald re. Lortie: I remember when I first heard about the study Schoolteacher. I was teaching in Japan in the early 1980s and attended a workshop on observation and ‘breaking the rules’ (Fanselow, 1987). We were talking about how we develop our expectations of how to act as teachers, and the presenter brought up what for me was a new idea of teacher socialization. He mentioned the idea of the ‘apprenticeship of observation’—the time we spend as students, observing our teachers and participating in their work from ‘the other side of the desk’—and how that shaped our expectations of what teachers do and how they behave. He commented, in passing, that the ideas came from a ‘great new book … Schoolteacher, by a sociologist, Dan Lortie’; we should check it out, he said. It slid by me, as a lot of book recommendations do; then almost a decade later, I picked up the book in graduate school. I was amazed by how apt the findings seemed to be. The study captured key issues I was thinking about in how people learn to teach, and gave succinct expression to complex experiences. On a personal level, they spoke to my own experiences as a high school French, and later ELT, teacher (Freeman, 2016). Unlike other studies that come on the scene, and then fade over time, Lortie’s ideas have had a durability to them that seems to come from the depth of their connection to teachers’ work and experiences. So as we were talking through the research that could anchor this book, I thought immediately of Schoolteacher.

Tessa re. Huberman: I was editing an article for The Teacher Trainer journal in 1991. The piece was written by Jenny Jarvis, then at Warwick University, who was explaining how she tried to make sure that the in-service courses that she ran for teachers from a variety of countries were maximally relevant to their needs. She asked participants to take their time filling out a thought provoking questionnaire before the course. Some of the questions were based on the work of Michael Huberman and she quoted from him, writing about different phases in a teacher’s career. His article sounded so interesting that I asked if she could send me a copy. She kindly did. I read it and the related book reporting his team’s study and have done so many times since then. I love the work for many reasons. First, for the initial impetuses Huberman gave for undertaking the research project, and that in designing his research he was so on the side of teachers. He writes, “It is worth remembering that the best expert of a given professional trajectory is precisely the person who has followed it” (Huberman, 1991, p. 20).

Then I loved the report for his dry sense of humour. The quotes from the teachers in his study are powerful, too. Most of all, I appreciate the respect he gave the teachers and the care with which he not only navigated the dimensions of age, cohort, psychological and physical maturation, political and social change, historical period, and educational reforms in the work but also consequently warned readers to take his team’s work as descriptive and not prescriptive.

Kathleen re. Tsui: I first met Amy Tsui when I attended a colloquium on sociocultural perspectives on learning and second language acquisition at the TESOL international conference in 2005 in San Antonio Texas. She presented a paper on young learners and collaborative group work in which she described a seismic shift in her thinking about curriculum from a syllabus-driven, cognitive processing model to an ecological, communities of practice model. I was familiar with this contrast from my own PhD research but was struck by how elegantly and persuasively she illustrated it with two simple sets of questions that teachers might ask themselves in preparing units of work. I later used these questions in an article about curriculum. This clarity of thinking grounded in examples of practice is a hallmark of her book on expertise. Her respect for the complexities of the lives of the four teachers she studied was evident in the way she wrote about their histories, dilemmas, doubts, and successes.

Organisation of Part 1

Having explained what interests us about each of the ‘trajectorists’, in the next section, ‘The Research’, we identify and elaborate specific ideas from their work. We end that section with a discussion of more recent research from the Learning4Teaching Project, which has studied how teachers in three countries understand the professional development they participated in, what they learned from it, and how they used it in their practice. The Learning4Teaching Project was designed and carried out by two of the authors, Freeman and Graves, and a group of colleagues in each of the countries involved. We include this research for two reasons. Like Lortie, Huberman, and Tsui, the studies focus on teachers’ perceptions of their learning. The studies are also transnational and large-scale, meaning they bring in perspectives of teachers across three countries, which allows us to consider current issues impacting on professional development in public-sector ELT.

For each of the research studies, we first describe the design, its purpose, the participants, and how it was carried out. We then list and discuss key ideas from the research that can help us to understand teachers’ professional development.

In the final section, ‘Implications of the Research,’ we explore some implications of the key ideas for teacher development. We discuss each researcher in turn, and how their ideas can help us to understand and shape our development as teachers. These implications provide the bridge to Part 2, which provides practical ideas for development over time.

B. The Research: Key Ideas About Teacher Development Over Time

1. Dan Lortie, Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study (1975)

In the introduction, we explained the rationale for the research we have chosen to frame the issues in this book: that the work either fomented or synthesised key ideas about teacher development over time, and that methodologically it represented teachers’ experiences from their own perspectives. Dan Lortie’s Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study, first published in 1975, fits these two criteria. The study broke ground in documenting teachers’ experiences of teaching and of learning to teach, in their own words. Process-product research, which prevailed at the time, studied how particular teaching processes ‘produced’ learning outcomes (see Dunkin and Biddle, 1974). In this methodological context, Lortie’s study, alongside Philip Jackson’s Life in Classrooms (1968), sought to chronicle teaching as it was done and experienced by teachers. The sheer scale of qualitative data gathering, combined with the care and complexity of ‘grounded’ analyses that worked to tease out themes and patterns in teachers’ own terms, helped to make Lortie’s study an original source for understanding teacher development.

1.1 About the Study: ‘Where Teachers and Students Meet’

Lortie begins by explaining the focus of the study:

It is widely conceded that the core transactions of formal education take place where teachers and students meet. Almost every school practitioner is or was a classroom teacher; teaching is the root status of educational practice … Although books and articles instructing teachers on how they should behave are legion, empirical studies of teaching work—and the outlook of those who staff schools—remain rare.

(p. vii)

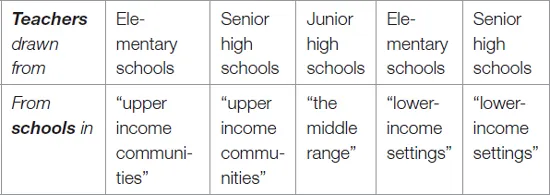

To examine teachers’ experiences, Lortie drew on in-depth interviews—94 in all—that were conducted in “the summer of 1963” (p. 246) in what he called the ‘Five Towns’ study of schools in New England, in the northeast of the United States. The teachers were chosen deliberately so that respondents fell into what he called “a five-cell sample (with equal numbers in each cell)” (p. 245) as depicted in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Lortie’s ‘five-cell’ research design

In New England in the 1960s, the ‘elementary’ schools would likely have included Kindergarten through Grade 5, or possibly Grade 6, while ‘junior high’ school would likely be Grades 6 or 7 and Grade 8, and ‘senior high school’ would have been Grades 9 through 12. Within each group, the choices of teachers to interview was random; for instance, “[i]n the upper-income high school cell, 20 names were randomly selected from a container cont...