![]()

1

Aceh

Nathan Shea

Introduction

The signing of the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) peace agreement between the government of Indonesia and the Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka in Bahasa Indonesia; GAM) on 15 August 2005 brought an end to a civil war that had seized the Aceh province for nearly three decades. The agreement was finalised just seven months after a return to talks between the two parties, following the Indian Ocean tsunami which devastated the region on 26 December 2004, radically altering the dynamics of the peace process.

Since 1976, GAM had fought for independence for the province which it saw as wrongly subsumed into the Indonesian state. Commanding popular sympathies through the 1990s in the face of a repressive military campaign by the Indonesian armed forces (Tentara Nasional Indonesia; TNI), the civil war was caught in the maelstrom of democratic political reform (reformasi) that swept across Indonesia following the Asian Financial Crisis. Spurred by the successful (yet violent) referendum and independence that birthed Timor Leste in 1999, widespread demonstrations for Acehnese sovereignty threatened the potential balkanisation of the Indonesian archipelago. The 1998 ouster of President Suharto, who had ruled the country for 31 years, and the dismantling of his New Order period appeared to be the catalyst for the reclaiming of ethnic identities that had been previously constricted. An increase in violence was also witnessed in the provinces of Papua, Maluku and North Maluku, Central Sulawesi, and in West and Central Kalimantan (Braithwaite et al. 2010; Shea 2016).

The Aceh Peace Process, mediated by two International NGOs – The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue from 1999 to 2003 and Crisis Management Initiative in 2005 – helped usher in a generation where international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) now play a significant role in peacemaking efforts. For nearly six years, Indonesian officials negotiated in Geneva and then Helsinki with GAM leaders in exile, far removed from the remote areas where armed groups clashed with Indonesian security forces over territory and influence. Ceasefires were regularly and often flagrantly ignored, until a sustainable political solution was negotiated over the first half of 2005. While the Helsinki Agreement offered limited enhancements over the autonomy already enjoyed by the province, it provided the inducements necessary for the demilitarisation of GAM and its evolution into a political party under the framework of ‘self-government’. Since signing the agreement the province has experienced more than a decade of relative peace, despite ongoing concerns on human rights violations and historical injustices.

This chapter examines the peacemaking process in Aceh, delving into how and why International NGOs became the preferred mediators in the conflict, and the difficult path they took to bring an end to violence in the region. First it outlines the origins of the conflict in Aceh, detailing the evolution of GAM as an independence movement born out of centuries of ethnic identity formation and fuelled by a modern history of harsh military suppression and exploitative regional policies. An examination of the peace process shows how local, national, and international efforts eventually led to the significant and rapid developments in late 2004 and 2005. Lastly, reflections are offered to help expand on some of the key takeaways from the peace process as a contained peacemaking exercise and its broader implications for the long-term socio-political environment in Aceh and Indonesia.

Conflict analysis

The province of Aceh sits at the northernmost tip of the Indonesian state on the island of Sumatra, separated from Malaysia by the Malacca Strait to its east and the Indian islands of Andaman and Nicobar across the Andaman Sea to its north. It is home to a largely homogeneous ethnic population; over 70 per cent of the population are ethnically Acehnese, while over 98 per cent of the population are Muslim (Ananta et al. 2015). Islam arrived in the region by 1250 AD, and for centuries Aceh acted as a gateway port between Southeast Asia and the Middle East, earning the region the nickname the Verandah of Mecca (Serambi Mekkah). Though the Dutch first established the Dutch East Indies Company in modern Indonesia in 1602, the Acehnese Sultanate withstood colonisation for centuries, only incorporated into the Dutch colony in the late nineteenth century.

Acehnese resistance to Dutch and then Japanese imperialism continued until the end of the Second World War, when there was real optimism that Aceh might gain sovereign status. However, Aceh’s incorporation into the newly independent Indonesian state in 1949 triggered persistent nationalist conflict that would span across the following six decades.

The precursor to GAM was the independence group Darul Islam, established in 1949 and led by Aceh’s first governor, Teungku Daud Beureu’eh. Darul Islam engaged in regular conflict with the Indonesia government throughout the 1950s, leading to the imposition of martial law by President Sukarno in 1957. Sustained military pressure eventually forced rebels into a negotiated settlement for the establishment of Aceh as autonomous province with special rights to Islamic laws in 1962.

These special autonomy provisions would, however, be slowly wound back over the years, leading to the resurfacing of nationalist aggression in the 1970s. Responding to increased popular dissatisfaction with Jakarta, a group of around 70 ideologically driven and well-educated professionals established in December 1976 the Aceh–Sumatra National Liberation Front (ASNLF), the precursor to the Free Aceh Movement (GAM).

GAM was led by Hasan di Tiro, a grandson of Teungku Cik di Tiro, a revered Indonesian ‘national hero’ who led the Acehnese fight against the Dutch colonial forces in the late nineteenth century. Hasan had studied in New York for a period and even worked at the Indonesian Mission to the United Nations; however, he was stripped of the position and his Indonesian citizenship after declaring his support for the Darul Islam movement in 1953. He would return to Indonesia eventually in 1974, reconnecting with contacts gained during his time with Darul Islam to begin the GAM movement.

At first glance, GAM was almost entirely an independence movement – grounded in the international fervour experienced in the 1970s and 1980s decolonisation movement and the UN’s mandated right to self-determination. Its 1976 independence manifesto reads:

The people of Acheh, Sumatra, exercising our right of self-determination, and protecting our historic right of eminent domain to our fatherland, do hereby declare ourselves free and independent from all political control of the foreign regime of Jakarta and the alien people of the island of Java.

In this sense, GAM sought to construct (or preserve) a sense of Acehnese nationalism encoded in the legacy of the sultanate as distinct from the Indonesian state created after the Second World War (Ansori 2012; Na Thalang 2009). It rejected the idea of Indonesian nationhood, instead seeing the country as a Javanese colonialist construct aimed at subjugating differing peoples in the archipelago. The suppression of Acehnese national identity became a key contestation over the course of the conflict. The Indonesian government prohibited the public display of symbols connected with GAM and Acehnese independence; the flag of the Free Aceh Movement was particularly targeted for repression and removal, often with punitive force (Schulze 2004).

The aspirations for independent nationhood were also driven by perceived resource exploitation and dispossession from Jakarta (Aspinall 2007). Di Tiro is said to have returned to Aceh in 1974 to bid for an oil pipeline project with the new Mobil Oil gas plant in the northwest of the province. With his bid unsuccessful, di Tiro alleged interference by Jakarta, and competition for access to natural resources remained a continuing concern of GAM as it pursued independence (Schulze 2004). As evidence of this, the Declaration of Independence of Acheh1 reads:

During these last thirty years the people of Acheh, Sumatra, have witnessed how our fatherland has been exploited and driven into ruinous conditions by the Javanese neo-colonialists: they have stolen our properties; they have robbed us from our livelihood … while Acheh, Sumatra, has been producing a revenue of over 15 billion US dollars yearly for the Javanese neo-colonialists, which they used totally for the benefit of Java and the Javanese.

In essence, it makes clear the direct connection not only with the territorial memory of Aceh but also a perceived grievance at the collection of natural resources and the maldistribution of profits gained from the lands’ exploitation. It makes direct correlations between the poor living conditions of Acehnese people and the lack of development of the region, despite perceived wealth. The nation-building project undertaken throughout Indonesia and driven by Jakarta was seen by GAM as the mere continuation of the exploitative practices implemented by the Dutch East Indies Company.

Following on from declaration of independence in 1976, the first iteration of GAM would be sustained until 1979, by which time most of the original members had fled into exile, been arrested, or been killed. Di Tiro himself had fled to Malaysia, and from 1980 moved to Sweden with a small group of the GAM leadership, where he would lead the movement in exile for the next 25 years.

By the late 1980s, GAM would again begin to radically disrupt the security environment in Aceh. Starting in 1986, GAM rebels underwent training in Libya, and in turn returning fighters would train others in the combat skills they had acquired overseas. In response, the Indonesia military launched in 1990 the ‘Military Operation Area’ or Daerah Operasi Militer (DOM), a heavy-handed counterinsurgency campaign targeting communities seen as sympathetic or providing sanctuary to the GAM. The military campaign, which lasted until 1998, was brutal in its implementation, described as a ‘systematic campaign of terror’ with the purpose of ‘strik[ing] fear into the population’ and pressuring them to withdraw support for GAM (Kelly 1995: 74, quoted in Schulze 2004: 4). By the end of the campaign, some 1,258 to 2,000 people had been killed, and nearly 3,500 tortured (Schulze 2004). There were 625 cases of rape and torture of women, while the number of persons disappeared varied between 500 and as many as 39,000. Twelve mass graves were investigated and over 7,000 human rights violations documented (International Crisis Group 2001; Schulze 2004).

Yet, while DOM was largely successful in repressing GAM as a rebel organisation, the movement was able to continue because: (1) the organisation’s leadership remained safe in exile in Sweden; (2) large numbers of GAM combatants were able to seek refuge in Malaysia, and (3) the heavy-handed military tactics deployed by the Indonesian military in the 1990s were significant in giving rise to a new generation of GAM fighters, those with close, personal experiences of the military crackdown (Schulze 2004). Under the significant civil repression employed by the government, the legitimacy of GAM as an alternative voice for a free and independent Aceh was strengthened.

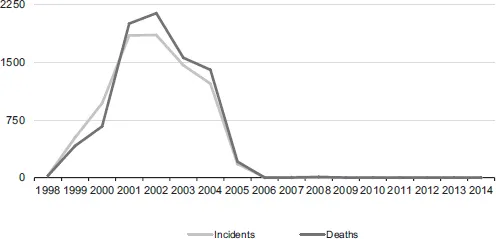

It took the collapse of the Suharto government in May 1998 in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis and Indonesia’s democratic reform process for space to be carved for the possibility of peace talks with GAM. The shift in power precipitated in Aceh an increase in the expression of anti-Jakarta and anti-military sentiments. Throughout 1998 and 1999, large-scale rallies and province-wide strikes were held in support of holding a referendum on independence similar to the one granted to Timor Leste. At the same time, a relaxing of punitive military operations allowed GAM fighters to return and regroup, particularly in the rural areas and small towns away from major cities. As a result, the number of violent incidents and associated deaths rose sharply during the reformasi period and through the six years that covered the peace process (see Figure 1.1).

Widespread public celebrations of the 23rd anniversary of the founding of GAM on 4 December 1999 were of such a scale that the Indonesian government and military were unable to intervene. At the same time, efforts by the Indonesian parliament (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat, MPR) to re-establish special autonomy within the province and to grant greater law-making power to the regional government did little to appease activists.

Despite the lifting of direct military operations in mid-1998, 447 civilians and almost 90 members of the security force were killed in the 19 months between the resignation of Suharto in 1998 and early 2000 (Aspinall and Crouch 2003). It was the election of President Abdurrahman Wahid in October 1999, seen as a reformist and part of the Democracy Forum opposition that opposed President Suharto, that would pave the way for negotiations between the Indonesian government and GAM.

Figure 1.1 Separatist incidents and deaths, Aceh, 1998–2014

The conflict resolution process

Moves towards peace talks took place in late 1999. The Henry Dunant Centre, now more commonly known as the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) – a new international non-government organization established in August 1999 in Geneva – approached President Wahid with the offer of dialogue. This came after several months of investigation and contact-building.

HD staff at the time had little experience in Indonesia; however, the organisation recognised space for peacebuilding interventions in the wake of democratic change and the referendum in Timor Leste. Connections within Indonesian government and civil society eventually led to a meeting between President Wahid and HD’s director Martin Griffiths in November 1999, where the organisation was able to raise its interests in facilitating dialogue between the government and GAM (Huber 2004).

The involvement of an NGO such as HD appealed to Indonesia for a number of reasons. International intervention in the 30 August 1999 Timor Leste independence referendum shamed the Indonesian government, with the United Nations Mission in East Timor (UNAMET) negotiated by Secretary-General Kofi Annan overseeing the vote that led to the former Portuguese colony’s secession. The TNI in particular were embarrassed, having come under significant international criticism in the violent aftermath of the referendum that forced the establishment of the Australian-led International Force East Timor (INTERFET) peacekeeping mission. In the face of strong anti-UN sentiment in Jakarta, HD were seen as a viable alternative, sufficiently international so as to appeal to the GAM leadership, while lacking official diplomatic status so as not to be able to bring coercive pressure (and embarrassment) to the government.

For GAM, there was an immediate interest in the negotiations, as they were seen to afford important international recognition of the struggle, particularly in Europe, where the senior leadership had been in exile for two decades. At the same time the internationalisation of the armed struggle helped the exiled leadership gain greater legitimacy for their position among GAM militias and Acehnese in Indonesia. The start of talks necessitated that the GAM leadership consolidate its command over its forces in Aceh, strengthening communication lines and coordination between local units.

HD facilitated the first meeting between the Indonesian Ambassador to the UN in Geneva, Hassan Wirajuda, and Hasan di Tiro in Geneva on 27 January 2000. Both acknowledged that they were unable to achieve a military victory in the conflict, and that the most productive method for resolving the stalemate was through negotiations (Aspinall and Crouch 2003). HD’s offer to mediate dialogue between the parties would then be officially accepted on 30 January by President Wahid on a state visit to Geneva.

The Humanitarian Pause

Further talks would take place between the Indonesian government and GAM in Geneva on 24 March and 14–17 April 2000. Initial discussions were aimed at forming a ceasefire for ending direct military confrontations between the parties and creating an environment perceived to be more amenable for discussion of a long-term political solution.

The talks culminated in the agreement of the ‘J...