![]()

Chapter 1

Online Experiences of Workplace Bullying Targets

TANJA MAIER AND NEIL S. COULSON

Chapter Summary

At the Institute of Work, Health and Organisations, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom, Tanja Maier and Neil S. Coulson examined the use of online support groups among workplace bullying targets. They carried out an exploratory study of motives and impacts in order to determine the increase in online support groups and their numerous well-documented benefits (Kurtz 1990, Meier 1997, White and Dorman 2001, Wright and Bell 2003, Ward and Tracey 2004, King and Moreggi 2007, Malik and Coulson 2008, Rains and Young 2009) might encourage bullied individuals to choose to participate in these groups. Thus, the aims of this study were to investigate:

1. individuals’ motives for accessing online support groups;

2. the perceived benefits and disadvantages of this participation;

3. how this involvement helps individuals cope with workplace bullying.

In total, 61 participants who accessed online support groups completed an online group interview of four open-ended questions. Inductive thematic analysis was applied and identified four recurrent themes which reflected participants’ online experiences:

1. unique features of online support groups;

2. searching for support;

3. impact of online groups;

4. negative experiences.

Although this study indicates that targets of workplace bullying generally benefit from accessing online groups, there are several disadvantages, which are also associated with such groups. The authors are grateful for the cooperation, help and support of the moderators of the online support groups and all participants, which made this study possible.

Background

WORKPLACE BULLYING

Workplace bullying has received increasingly more attention within the field of occupational psychology due to its damaging consequences to individuals and organizations alike. Media reports and government-supported public awareness campaigns such as the Trade Union Congress’s Beat Bullying at Work (TUC 1998) have helped workplace bullying gain recognition as a major occupational stressor (Coyne, Seigne and Randall 2000). In addition, several national studies have highlighted issues surrounding workplace bullying. A review of 30 European studies by Zapf, Einarsen, Hoel and Vartia (2003) revealed that 1–4 per cent of employees are exposed to workplace bullying, while 8–10 per cent experience other forms of negative behaviour. Other studies have published bullying-related rates that vary from 3.5 per cent in Sweden (Leymann 1996), 8.3 per cent in Denmark (Ortega, Hogh and Pejtersen 2009), 8.6 per cent in Norway (Einarsen and Skogstad 1996), 10.1 per cent in Finland (Vartia 1996), 10.5 per cent in the UK (Hoel, Cooper and Faragher 2001), and 14 per cent in Spain (Trijueque and Gómez 2010), to as high as 28 per cent in the USA (Lutgen-Sandvik, Tracey and Alberts 2007).

Thus far, the existing literature has concentrated on the detrimental impact that workplace bullying inflicts on its targets and on organizations as a whole. In 2007, annual organizational costs associated with workplace bullying in the UK were estimated at around £13.75 billion (Giga, Hoel and Lewis 2008) and included absenteeism, staff turnover rates, lower work performance and productivity (Appelbaum, Semerjian and Mohan 2012, Lind, Glasø, Pallesen and Einarsen 2009, Salin, 2003a). According to Rayner, Hoel and Cooper (2002) approximately 25 per cent of bullying targets and witnesses quit their position at some point.

In terms of the negative effects of workplace bullying at an individual level, several studies have reported severe health-related problems among bullying targets. For example, physical problems include sleep disturbances, loss of appetite, chronic diseases and stress symptoms (Einarsen 1999, Lind et al. 2009, Moayed, Daraiseh, Shell and Salem 2006). Psychological problems include anxiety attacks, depression, suicidal tendencies and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Appelbaum et al. 2012, Leymann and Gustafsson 1996, Lind et al. 2009). There are also social and financial issues, such as relationship issues with friends and family (Keashly and Jagatic 2003) and sudden or long-term unemployment (Einarsen and Mikkelsen 2003).

Although the gravity of this issue has been researched extensively and empirically within the existing literature, attempts to agree on a more precise definition of workplace bullying have so far failed. However, Salin defines bullying as ‘repeated and persistent negative behaviour, which involves a power imbalance and creates a hostile work environment’ (2003b: 31). The concept of power differences is a common aspect in most definitions of workplace bullying (Salin 2003b). Hoel and Salin (2003) conjecture that bullying may result from an interrelationship between a person’s perception of having both the ability (for example, higher power) and the motivation to bully others, as well as the presence of specific triggering situations. Emphasis may be placed on power imbalances stemming from individual differences, as well as from societal and situational factors (Cleveland and Kerst 1993).

Gender is often associated with power imbalances (Cleveland and Kerst 1993, Aquino and Bradfield 2000, Salin 2003b) and empirical research regarding the relationship between gender and workplace bullying identifies a higher prevalence rate of workplace bullying towards women (Salin 2003b). A study by Björkqvist, Österman and Hjielt-Bäck (1994) reported that women are more prone to workplace bullying compared with men and approximately 25 per cent of targets name their gender as the reason for the negative treatment. Furthermore, Vartia and Hyyti (2002) note that female police officers are targeted by bullies more often than male police officers and Salin (2003b) asserts that as many as 11.6 per cent of female participants are bullied at work, compared to only 5 per cent of men.

ONLINE SUPPORT GROUPS

The internet has become a vital tool for people seeking information and advice related to a variety of issues (Powell and Clarke 2002) including workplace bullying. Morahan-Martin (2004) noted that out of all information searches by internet users, approximately 4.5 per cent are health-related. Alongside a vast amount of information and resources, the internet has also contributed to the development of online support groups devoted to the issue of workplace bullying. Online support groups may be preferred by users over traditional face-to-face support groups for different reasons. First, the absence of geographical or temporal boundaries engenders the possibility of asynchronous written communication at the user’s convenience. This enables users to access crucial information and support whenever needed (Malik and Coulson 2008). Second, the lack of geographical restrictions allows people to draw from a wider source of information, experiences and perspectives provided by a larger heterogeneous mix of members (Wright and Bell 2003).

The anonymity that online groups provide for members facilitates discussion of sensitive topics, such as workplace bullying, and thereby encourages people to self-disclose their personal issues in a safe environment (White and Dorman 2001). Furthermore, King and Moreggi (2007) argue that the asynchronous nature of online groups gives users the possibility to carefully read other members’ queries and responses and take time in preparing their own answers and questions. This could help to minimize potential misunderstandings and to reduce any existing time constraint to respond.

Previous literature concerning health-related online groups has demonstrated that participation in such groups can have various benefits, including newly created relationships with like-minded people (Ward and Tracey 2004), exchange of information, experiences and advice that improve users’ coping strategies (Meier 1997) and emotional and informational support, which in turn improves members’ psychological health and increases their self-efficacy to manage their own issues (Rains and Young 2009). Similarly Kurtz (1990) argues that sharing experiences with people undergoing similar situations provides bullying targets with the necessary emotional support and validation to enable them to reconstruct a positive self-identity.

Although the body of literature regarding the advantages of online groups is steadily growing, research into the potential disadvantages is still relatively scarce. In particular, the lack of non-verbal cues within anonymous online groups can contribute to potential misunderstandings between group members (White and Dorman 2001, Finfgeld 2000). In addition, either the total absence or the presence of unprofessional moderators controlling the information that is reciprocated between members may lead to the exchange of inaccurate, inappropriate or outdated data (Coulson 2005, Finfgeld 2000, Hoffmann, Desha and Verrall 2011). This could give rise to aggressive or hostile interactions (Finfgeld 2000).Finally, the asynchrony of online communications may result in potential delays of urgently desired responses (White and Dorman 2001).

The increasing number of online support groups and their benefits might encourage bullied individuals to participate in these groups. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the rationale behind why workplace bullying targets choose to access online support groups; it is also the first to investigate the consequences of participation in such groups. Furthermore, group members’ experiences of accessing online groups, and whether they have encountered any disadvantages related to this participation, have thus far received little attention.

Methodology

PROCEDURE

The recruitment of participants for this study was conducted by posting messages on the bulletin boards of various workplace bullying online support groups. The moderators of these online groups were contacted beforehand to seek permission for posting a link to a short online group interview available to the group members. Additionally, the nature and purpose of the study were conveyed to the moderators. Once permission had been obtained, a note explaining the purpose of the study was posted to invite members to participate in the online group interview. Members willing to take part were directed to SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com) a cloud-based online survey company, where they received additional information regarding the nature of the study and their rights as participants. After providing informed consent, each participant was required to create an original six-digit code for retrieval purposes, should they wish to withdraw from the study.

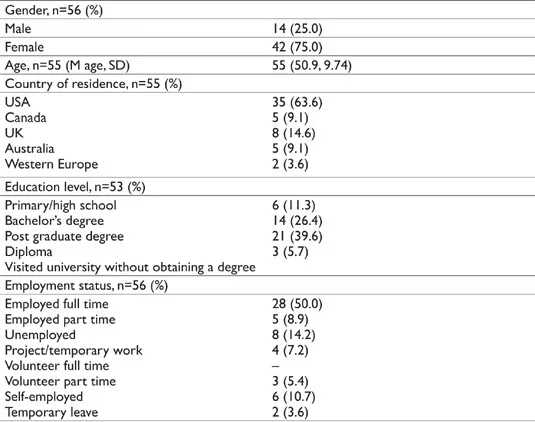

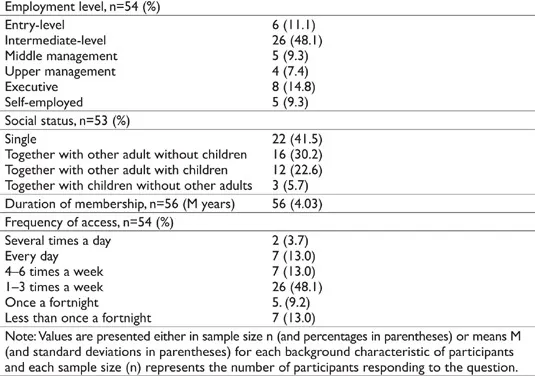

During the online group interview, participants were asked to provide sociodemographic information including gender, age, country of residence, education level, employment status, employment level, social status, duration of group membership, and frequency of accessing online support groups (see Table 1.1). Furthermore, participants were invited to answer four open-ended questions related to their online experiences within support groups (see Figure 1.1). Previous studies investigating online experiences of online support group users have employed similar procedures and questions (for example, Buchanan and Coulson 2007, Malik and Coulson 2010).

Open-ended questions for participants

1. Why did you join this online support group?

2. What do you think are the main advantages of participating in an online support group?

3. What do you think are the main disadvantages of participating in an online support group?

4. Has being a member of an online support group made any difference to how you cope with being bullied at work? If so, could you please give some examples?

Figure 1.1 Questions asked of participants in online support groups

Source: Author.

PARTICIPANTS

In total, 61 participants who accessed online support groups completed the online group interview. Two individuals were excluded due to multiple responses. Of all the participants, the majority were females (75 per cent) and residing in the US (63.6 per cent). The age of the participants ranged from 27–71 years (M age=50.9, SD=9.74). Table 1.1 shows a summary of the descriptive statistics of sociodemographic characteristics collected from participants.

Table 1.1 Summary of sociodemographic characteristics of participants

Source: Author.

DATA ANALYSIS

In order to identify the online experiences of workplace bullying targets who access online groups, inductive thematic analysis was performed on all responses obtained through the online group interview. Since thematic analysis allows for the identification of insightful common patterns or themes across all question responses, this qualitative technique was deemed to be appropriate for this purpose. The data analysis was performed in accordance with the guidelines outlined in Braun and Clarke (2006). First, the responses were read repeatedly in order to become familiar with the entire dataset. Simultaneously, the data was reviewed for similarities and differences. Second, recurrent and interesting patterns across all responses were coded and organized into potential themes using mind-maps. Third, the themes and related extracts were grouped together and labelled accordingly. It was verified that all significant statements had been included in the themes, and that the created theme definitions were coherent with all coded extracts.

Given that it is possible to employ thematic analysis within various theoretical frameworks, Braun and Clarke (2006) recommended that researchers should indicate the theoretical framework used for the data analysis. In order to investigate participants’ motivations and experiences, the essentialist/realist framework was administered on the entire dataset and themes were established at the semantic level.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Nottingham’s Institute of Work, Health and Organisation’s Research Ethics Committee in accordance with the ethical code of conduct released by the British Psychological Society. As per previous studies examining online support groups, ethical considerations focused on the participants’ right to withdraw from the study, confidentiality and informed consent (for example, Malik and Coulson 2008).

All participants were provided with detailed information regarding the nature and methodology of the study and their right to withdraw from the research. For this purpose, participants were provided with the contact details of all researchers should any concerns or questions arise or if participants wished to withdraw their responses from the research (no participant chose this option). The original six-digit code created by each participant prior to completing the online group interview aided the identification of their responses.

To ensure privacy and confidentiality, participant statements were anonymized by removing all personal information except for age and gender, thus making them non-retrievable. By consenting to take part in the study, all participants gave their approval for their statements to be used in case of publication.

Research Results

The inductive thematic analysis identified four major themes related to the rationale behind why individuals access workplace bullying online support groups, and their experiences of participation in such groups. Themes were identified by analyzing across all question responses, as opposed to identifying themes from responses to each individual question in the online group interview. These emergent themes were labelled as:

1. unique features of online support groups;

2. searching for support;

3. impact of online groups;

4. negative experiences.

The extracts were taken verbatim without correcting for grammar or spelling mistakes, and are reproduced here with minor corrections for the purposes of clarification.

UNIQUE FEATURES OF ONLINE SUPPORT GROUPS

Several participants noted the unique features of online support groups when describing the benefits of accessing such groups instead of engaging in face-to-face conversations. In particular, one respondent referred to the convenience with which online groups could be accessed: ‘Online support groups are easier to find than groups in your physical local area’ (Female, 54).

The anonymous environment that online support groups provide for their members seems to further encourage the communication of sensitive issues and aids group members in the disclosure of negative experiences: ‘Not having to speak face-to-face with others after being a target of workplace mobbing and the anonymity the online group provides is also a draw and aids my ability to want to talk about the issues I have faced’ (Male, 42).

Several respondents explained how the ability to share personal issues coupled with the anonymous nature of online groups delivered a safe environment in which they could express their emotions without fear of criticism or disbelief: ‘They [online groups] are a great place to vent about the experiences one has had’ (Male, 57); ‘It [online group] also provides a place to vent while being anonymous (you wouldn’t want your words getting back to the employee/boss)’ (Female, 29).

In addition to encouraging open communication about one’s feelings and experiences, one respondent valued the fact that online groups provide the possibility ‘to “observe” without participating’ (Female, 56) while another stated that the asynchronous nature of online conversations has the benefit of reducing any existing time constraints to respond, and thu...