![]()

1 / “It’s Neolithic!”

LATE IN THE AFTERNOON of November 10, 1958, a green Land Rover lurched down a narrow dirt road in south central Turkey, about thirty miles southeast of the city of Konya. Three British archaeologists were packed inside. A frigid wind gusted from the south, blowing swirls of cold dust over the surrounding wheatfields. The Land Rover pulled up to the edge of a massive hill that stood out prominently from the flat plain. The archaeologists already suspected that this was no ordinary hill. The crunch of the tires went silent, and the three men climbed out to have a closer look.

The leader of the group was James Mellaart, thirty-three years old, pudgy, round-faced, his eyes darting to and fro excitedly behind dark-rimmed glasses. Mellaart lit a cigarette and stared out at the mound. The motor of a tractor droned in the distance. A flock of gray-throated great bustards circled overhead, their large wings swishing in the air. At Mellaart’s side, buttoning his coat against the cold, stood David French. Mellaart and French were visiting scholars at the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, the BIAA. Both men specialized in the prehistory of Anatolia, the vast plateau that makes up most of modern Turkey. (Prehistory is, in short, everything that had happened to humanity before the invention of writing some 5,000 years ago, during the Near Eastern Bronze Age.)

The third archaeologist was Alan Hall, a student at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. Hall was studying the Classical period in Anatolia, from about the eighth century B.C. to the fourth century A.D., when Greek and Roman cultures spread from Europe into Asia. Mellaart had never learned how to drive, and Hall, whose Land Rover it was, had been kind enough to lend it for the mission. For more than a week the threesome had crisscrossed the Konya Plain, looking for signs of early human settlements. In theory this archaeological survey was meant to record any and all signs of ancient occupation, from all epochs, with an eye to possible future excavations. But Mellaart had come to Turkey with a mission: he was out to prove that Anatolia had played a pivotal role in prehistory. He had little interest in anything later than the Bronze Age. Despite the considerable remains of Classical civilization he and his colleagues came upon, Mellaart would dismiss even the most interesting of these ruins as “F.R.M.,” short for “filthy Roman muck.”

French shared Mellaart’s passion for ancient Anatolia. Earlier that same year, he had dug with Mellaart at Hacilar, a 7,500-year-old village in western Turkey. Those excavations were already pushing back the earliest evidence for civilization in the region by several thousand years. Turkey was still relatively untouched by archaeological trowels. The unexplored horizons of its austere landscape beckoned to young archaeologists like French and Mellaart eager to make important discoveries and names for themselves. Yet as late as 1958, Anatolia was a passion in which few other archaeologists partook. Most experts believed that the Anatolian plateau was little more than a backwater during prehistoric times. The real action, they were convinced, had been farther east, at Neolithic sites like Jericho in Palestine and Jarmo in Iraq. There, some of the earliest known farming villages, 10,000 years old and more, had been unearthed in the early 1950s.

That dismissive attitude, however, had left a dilemma. Archaeologists were confident that the earliest farming settlements had sprouted in the Near East. A few thousand years later, Neolithic villages began cropping up in Greece, then the rest of Europe. It was logical to assume that farming had spread overland, from Asia to Europe, by the most direct route: via Anatolia. But there was little evidence to support this idea. Anatolia, the supposed land bridge for the westward spread of farming and settled life, had nothing to show for itself. As late as 1956, Mellaart’s boss, Seton Lloyd—the BIAA’s director in Ankara and a veteran of three decades of archaeological campaigns in the Near East—had written that “the greater part of modern Turkey, and especially the region more correctly described as Anatolia, shows no sign whatever of habitation during the Neolithic period.” Some experts proposed instead that farmers had traveled from Asia to Greece by sea. This notion grew in popularity after excavations on Cyprus during the 1930s and 1940s revealed a sophisticated Neolithic community on that Mediterranean island, which later radiocarbon dating showed to be nearly 8,000 years old.

As Mellaart fidgeted and French shivered, they could hardly dare to believe that they were about to prove the experts wrong. Nor did they imagine that they would do far more than simply score points in what, to nonexperts, might have seemed like a fairly esoteric debate. In just a few years, discoveries at the impressive mound they now stood before would make headlines around the world, electrify the archaeological community, and revolutionize our picture of Neolithic technology, art, culture, and religion. And they would make Mellaart’s reputation as one of the most brilliant, as well as most controversial, figures in archaeological history.

At the moment, however, all that lay in the future. During the previous week or so, the three archaeologists had already accomplished enough to make their meandering journey worthwhile. Their survey had charted more than a dozen new settlements dated to the Chalcolithic, or Copper Age, the epoch sandwiched between the earlier Neolithic and the later Bronze Age. Most archaeologists were willing to accept that Anatolia had been occupied during the Chalcolithic. Yet before Mellaart had begun trekking the plateau some years before, few of these sites had been recorded. Not that they were so difficult to find. To the great convenience of archaeologists searching for ancient villages, early Near Eastern settlers had two enduring habits. First, they often constructed their houses in mud brick, a building material with a lifetime of less than one hundred years. Second, when they rebuilt their homes, they usually did so on the same spot, using the ruins of the earlier structures as new foundations. Over hundreds of years, as these successive building levels lifted the villages higher and higher above the surrounding landscape, they eventually formed considerable mounds—or, in archaeological parlance, tells, after the Arabic word for “tall.”

Long before Mellaart began working in Turkey, archaeologists had been mapping mounds across the Near East. One pioneer was the British archaeologist Max Mallowan. Accompanied by his wife, mystery writer Agatha Christie, Mallowan recorded hundreds of tells in Iraq during the 1930s while working for the British School of Archaeology in Baghdad. Seton Lloyd, who later took over this project, expanded the list to more than 5,000 mounds by the time he left Iraq for Turkey in 1948. But while Near Eastern mounds are relatively easy to find, some of them are layered with so many thousands of years of occupation that earlier levels tend to be compressed and distorted by later ones. As a result, archaeologists trying to understand their stratigraphy—that is, which occupation level belongs to which time period—often face a daunting challenge. A good example was Jericho, a complex site tackled by the British archaeologists John Garstang in the 1930s and Kathleen Kenyon in the 1950s. Garstang and Kenyon had to make sense of more than 10,000 years of archaeological deposits, which were first laid down when Jericho was a seasonal camp for hunter-gatherers and then continued to build up during the Neolithic period, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age.

The tell that now loomed before Mellaart and his colleagues looked equally daunting. The oval-shaped mound was huge, a third of a mile long and some sixty feet high at its highest point. It was blanketed with wild grass and ruin weed, a bushy plant often found growing on Near Eastern tells. French and Hall trudged up the hill to have a look at the top, while Mellaart stayed below. As he prowled around the perimeter, eyes glued to the ground, Mellaart began spotting shards of a burnished, chocolate-brown pottery. He also spied hundreds of small pieces of glassy black volcanic obsidian, some fashioned into blades shaped like long prisms. Mellaart’s heart began to race. He knew this pottery. He knew this obsidian. During the late 1930s, after Garstang had finished his work at Jericho, the pioneering archaeologist went on to excavate a large Neolithic settlement near the Turkish city of Mersin, on the Mediterranean coast. Mellaart had long thought that Garstang’s discoveries should have opened archaeologists’ eyes to the importance of Anatolia. But Mersin was so close to northern Syria that the experts didn’t associate it with Anatolia at all. They preferred to lump it in with better-known Neolithic cultures in Syria and Mesopotamia.

The pottery and obsidian under Mellaart’s feet were nearly identical to the Neolithic artifacts that Garstang had found at Mersin. The shards were practically oozing out of the mound. But what was at the top? At Mersin, Garstang’s Neolithic village had been overbuilt with Chalcolithic, Bronze Age, Hittite, Greek, Byzantine, and finally Arab settlements. Mellaart looked up to see French and Hall racing down the tell towards him. “It’s Neolithic! It’s Neolithic at the top!” they shrieked. Mellaart shouted back, hardly believing his ears, “It’s bloody Neolithic at the bottom!”

On this bitterly cold November day, Mellaart, French, and Hall had proved once and for all that Anatolia had been occupied during the Neolithic period. But they had done much more. They had discovered the biggest and best-preserved prehistoric settlement found to date. It sheltered a thousand years of pure Neolithic occupation, from bottom to top, with nothing—certainly no filthy Roman muck—to disturb its delicate mud-brick stratigraphy.

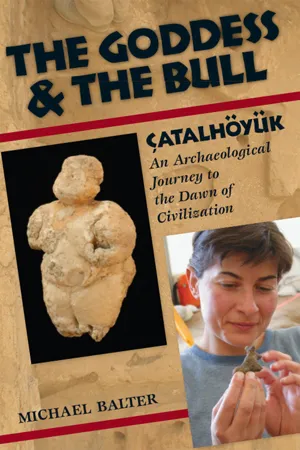

THAT EVENING the three checked into a hotel in the nearby town of Çumra, where they toasted their discovery long into the night with glasses of raki, the potent, aniseed-flavored Turkish liqueur. The next morning they returned briefly to collect samples of pottery and obsidian, and, as Mellaart later said, “to make sure it was still there.” Mellaart’s maps told him that this hill was called Çatal Hüyük, which meant “mound at the forked road” in Turkish. (Many years later Turkish authorities modernized the spelling to the present-day Çatalhöyük.) Local villagers confirmed that he had the right mound.

In Mellaart’s later report on the discovery, published in Anatolian Studies, the BIAA’s journal, his excitement had not abated. After briefly mentioning the fourteen new Chalcolithic sites the survey had found, Mellaart wrote, “Even more important is the discovery of one huge Neolithic town-site…this mound is nearly three times the size of Jericho…were excavations undertaken here, some extremely important conclusions might be reached about the earliest settlement on the Anatolian plateau.” As the senior member of the survey team, Mellaart, according to archaeological tradition, had first dibs on the right to excavate the site. Certainly no one would question whether he was the right man for the job.

TO HIS FRIENDS, he has always been Jimmy. His enemies call him Jimmy too. Both friend and foe agree that Mellaart was an archaeological genius, with an unequaled nose for sniffing out ancient settlements. If the legend was born on the Anatolian plateau, the man himself came into the world in London, on November 14, 1925. According to Mellaart’s account of his family’s history, his father’s ancestors were Highland Scots who eventually settled in Holland. Mellaart’s father was a Dutch national who had emigrated to England shortly before Mellaart was born; his mother came from Northern Ireland. His father was an art expert who had studied with the Dutch Rembrandt scholar Abraham Bredius, who is perhaps best known for being taken in by the notorious Vermeer forgery Supper at Emmaus.

Mellaart spent his early childhood in a fine house in the West London borough of Chelsea, surrounded by art and talk of art. His father made a good living advising connoisseurs on their purchases, especially of Old Master drawings. But when Mellaart was seven years old, everything changed. The 1929 Wall Street crash, and the worldwide depression that followed, had dried up the art market. By 1932 his father gave up and moved the family, which now also included Mellaart’s younger sister, to Amsterdam. Soon after, his mother died. Mellaart was never told how or why. His father refused to talk about it. But his mother’s death marked him indelibly, especially after his father remarried.

Mellaart’s father moved the family several times, from Amsterdam to Rotterdam to The Hague, where the boy started high school. Then, in May 1940, the Germans invaded and occupied the Netherlands. When Hitler began building his Atlantic Wall right through the coastal suburb where they lived, Mellaart’s father picked the family up again and settled in an eighteenth-century castle near Maastricht. But right after Mellaart took his final exams at the local high school, he received a letter from German authorities ordering him to report to the Maastricht railroad station. He was to be sent to Germany to join the Nazis’ slave labor force. Instead he went underground. Mellaart’s father had many friends in Dutch museums; one of them found a job for him at the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, where he was put to work mending broken pottery and making plaster casts of archaeological finds.

In high school Mellaart had developed a keen interest in ancient Egypt. In Leiden he was befriended by a professor of Egyptology at Leiden University, Adriaan de Buck, who was best known for his extensive translations of texts found on ancient Egyptian coffins. Since the Nazis had closed the university, the elderly de Buck had no one to teach. He encouraged Mellaart to study Egyptian languages. Each week the young man would come around for tea and tutoring sessions. But Mellaart, surrounded by the fabulous riches in the museum, had already decided he wanted to be an archaeologist rather than a linguist. In those days the best places in Europe to study archaeology were London and Oxford.

In 1947 Mellaart landed a place in the undergraduate archaeology program at University College London. He continued to pursue his fascination with ancient Egypt and, in particular, with the origins of the so-called Sea Peoples, raiders and plunderers who plagued the eastern Mediterranean beginning around the thirteenth century B.C. They made a number of attempts to conquer Egypt, an ambition that was ultimately defeated by Pharoah Ramses III around 1170 B.C. The Sea Peoples were more successful in the Levant, the region along the eastern Mediterranean coast. One group of Sea Peoples, the Philistines, became the biblical enemies of the Israelites. Just where the Sea Peoples came from is still a matter of debate. Much of their pottery, which has been unearthed at sites they apparently destroyed—the pottery lies in stratigraphic layers just above the destroyed settlements—is similar to that made by the Mycenaeans from Bronze Age Greece.

Some archaeologists have put the finger farther west, on the Sardinians, Sicilians, or the Etruscans. Mellaart, while a student in London, became an enthusiast of yet another minority viewpoint: the Sea Peoples who harassed Egypt and the Levant, he decided, must have come from the north—that is, from Anatolia. Before long, the pursuit of this iconoclastic hypothesis would take Mellaart to Turkey. But first he had to learn to dig.

AT THE TIME MELLAART was coming of age as an archaeologist, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, British field archaeology had long been dominated by two giants: Kathleen Kenyon and her mentor, Mortimer Wheeler. In North America the so-called Wheeler-Kenyon school of excavation had its parallels in what is more simply called the Stratigraphic Revolution, exemplified by Alfred Kidder’s meticulous work on the Pueblo cultures of the American Southwest. This generation of archaeologists had borrowed the concept of stratigraphy, meaning “stratification,” from geologists who used the term to describe the strata that made up the earth’s crust. Just as volcanoes, rivers, and lakes had deposited successive layers of rocks and sediments on the earth’s surface, so did successive waves of ancient peoples leave behind the stratified deposits of their civilizations. The archaeologist’s job, Wheeler and his like-minded colleagues insisted, was to carefully record the position of each find—whether it be a pottery shard, a grinding stone, or a human burial—so that it could be correctly assigned to the culture that had produced it.

Today it may seem obvious that the most recent occupation layers at an archaeological site will usually be found at the top and the oldest at the bottom, but a full appreciation of this basic premise was slow in coming. For one thing, it meant treating the biblical account of creation, which put the age of humankind at no more than 6,000 years, with considerable skepticism. It was also necessary to acknowledge that our own species is the fruit of millions of years of biological and cultural evolution. Before the middle of the nineteenth century, when scholars finally began to accept these once-radical notions, it was difficult for archaeology to take off as a scientific discipline in its own right. An early and notable exception was the work of Thomas Jefferson, whom Wheeler himself credited with conducting “the first scientific excavation in the history of archaeology”—a carefully recorded 1784 trench through a burial mound on Jefferson’s property in Virginia. Unfortunately, as Wheeler lamented, Jefferson was too far ahead of his time: “This seed of a new scientific skill fell upon infertile soil.”

Two major events finally gave archaeology the lift it needed. One was the publication in 1859 of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, which put the theory of evolution on a firm scientific basis. The other, also in 1859, was the visit of a delegation of eminent British scientists to France’s Somme River. Since 1837 amateur archaeologist Jacques Boucher de Crèvecoeur de Perthes had been claiming to have found human-made stone axes buried in the river’s banks, in intimate association with the bones of extinct animals. Until the British confirmed his conclusions, Boucher de Perthes, the director of a local customs house, was hard put to convince anyone that the Ice Age humans who made the tools had lived long before the great flood described in the Bible.

Many more years would pass before archaeologists would adopt the rigorous scientific methods Wheeler and others had begun advocating by the 1920s. “There is no right way of digging, but there are many wrong ways,” Wheeler, ever the scold, declared. He was particularly disdainful about the celebrated excavations at Troy and Mycenae carried out in the 1870s by the German banker and adventurer Heinrich Schliemann—the Indiana Jones of his day—which had done so much to stoke the public’s appetite for the romance of archaeology. “We may be grateful to Schliemann” for uncovering these fabulous sites, Wheeler wrote, “because he sh...