![]()

Chapter 1

The Presence of the Past: A Historical Ecology of Basque Commons and the French State1

Seth Murray

Introduction

The Pyrenees Mountains in the Basque region of southwestern France offer a bucolic pastoral landscape of verdant forests, whitewashed farmhouses, and sheep herds grazing in luxuriant meadows. Across much of this landscape, the vast pastures are common-pool resources that are collectively managed and used, and these commons have long served as vitally important resources to Basque farmers. In agricultural contexts, land use practices shape how resources are utilized across space and time, and these in turn influence the spectrum of human activities. Commons in the Pyrenees Mountains, as elsewhere on the planet, exist because specific ecological constraints require strategies adapted to them by users; thus, commons and common-pool resources must be examined as culturally and historically contingent products.

In this chapter, I examine the long-term development of Basque commons in the border region of southwestern France by contextualizing this regime within the framework of historical ecology. By framing how the Basque commons in this part of the Pyrenees Mountains have been continuously used and managed since the 18th century, I suggest that Basque agriculture has long contended with the influences of the French and Spanish states, although the nature of these exogenous influences dramatically intensified over the past 40 years. Technological developments and increases in subsidies from both France and the European Union have abetted the mechanization of agricultural labor, which contributes to social fragmentation. Demographic shifts and the cumulative effect of migration patterns over the past century dramatically recomposed the make-up of farming communities. Moreover, as in many industrialized and industrializing economies, the trend towards higher yields and agricultural productivity pushed farmers to adopt controversial new strategies that further fray and stress key social Basque institutions, such as cooperative neighborhood work parties (referred to as auzolan in the Basque language), leading farmers to operate more autonomously and not rely on the support of their neighbors during peak labor periods.

The decline of these networks for communal assistance in agricultural tasks highlights an increase in local competition over the common-pool resources that comprise the commons discussed in this study. This is not to suggest that Basque farming practices were unchanged until recent decades, but rather to highlight the diachronic importance of the commons as both ecological and economic resource. Overall, these changes have important implications for the current state of agricultural practices and common-pool resources in the Basque region. The intention of this chapter is not to explicate all of the contemporary issues facing Basque farmers and others in the Pyrenees Mountains today, which is the goal of many other chapters in this volume. Instead, I intend to ground an explanation of the processes of modernization and development within the context of larger historical trends. In order to understand the challenges facing Basque commons, the sustainability of common-pool resources, the resilience of management regimes, the emergence of new groups and actors that contest the root causes of agricultural changes and their subsequent social impact, our analysis must consistently visualize the presence of the past.

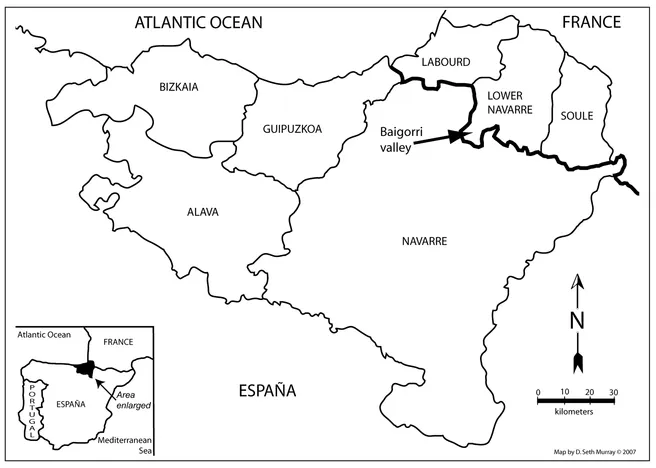

The study area: the Basque region and the Baigorri Valley

This chapter draws on research conducted since 1999 in the Basque region of southwestern France, more specifically in the Baigorri Valley, located in the province of Lower-Navarre, approximately 50 kilometers inland from the Atlantic coast (see Figure 1.1). Although the Basque Country has historically never truly formed a unified political entity, the seven Basque Provinces are typically thought to constitute a coherent cultural unit. While this assessment, as well as any discussion of Basque distinctiveness, is certainly subject to interpretation and much debate, there is little doubt that this area is situated in a politically complex landscape environment. The Basque region is today located within the borders of the nations of France and Spain, and these two polities have exerted, and continue to exert, strong centripetal political forces on their geographical peripheries, including those in the Pyrenees Mountains.

The Baigorri Valley lies on the international border between these two nation states, surrounded by Spanish territory on three sides and connected to France through its northern side. This is a predominantly agricultural, rural, and mountainous part of the Basque region, where farmers mostly raise sheep and some cattle. The Baigorri Valley is narrowly configured in a north–south orientation, with mountain ranges surrounding the farmsteads and villages that are located in valley bottom that: is never more than six kilometers wide. The average farm comprises a little over 22 acres, which is not sufficient pasturage to support the average herd size of 150 sheep over an entire year. An important feature of the landscape that enables farmers to subsist with such small land holdings are the mountain ranges surrounding the valley, which consist of more than 12,000 hectares of common-pool pastures and forests (equivalent to half of the valley's total surface area). Commons are of central importance to pastoralism in this area because this allows farmers to send sheep herds to graze in the mountain pastures from May to October, while in the meantime they produce hay in their privately owned fields located in the valley bottom. The livestock return from the commons in the upland for lambing and milk production during the rest of the year. This annual movement of sheep between two ecological zones is called transhumance. This cycle of transhumance is integral to agricultural practices in the Baigorri Valley, as it is throughout much of the Pyrenees Mountains, and farmers' success is ultimately predicated by the availability of these common-pool resources (Ott 1993).

Figure 1.1. The Basque region and the Baigorri Valley. Seth Murray 2007.

In this chapter, I first present the key theoretical notions of the commons, and then address the salience and analytical potency that historical ecology offers to the expansive literature accumulated in the wake of Garrett Hardin's thesis on the 'tragedy of the commons.' In the second part of the chapter, I provide a historical perspective in order to better understand the evolution of relationships between farmers and the common-pool resources that are central to agriculture here. I examine the historical role of the French state as it progressively expanded its control and sovereignty over this border region, and consider how this process shaped the use and management of the Basque commons over time. In the last section, I draw from more recent ethnographic research conducted in the Baigorri Valley to understand the place that common-pool resources now occupy in the livelihoods of sheep farmers. I discuss the socioeconomic transformations of the 20th century that catalyzed a fraying of the social fabric in these communities and that by extension impacted Basque commons. The historical context provided here helps not only to understand the origin of these transitions, but also to distinguish important ecological and socioeconomic parallels with the other case studies presented in this volume.

Historical ecology of the Commons

Historical ecology has emerged in the past 15 years as an integrative theoretical umbrella that identifies the dialectical network of causes and effects through which human acts are made manifest in the landscape (Crumley 1994). By simultaneously accounting for local-, regional-, and transnational-level influences, historical ecology improves our understanding of the relationships between humans and their environment, and is attentive to the critical roles that social power and the political economy play in natural resource use. An analysis and interpretation of commons should include 'a complete explanation of ecological structure and function [that] must involve reference to the actual sequence and timing of the causal events that produced them' (Winterhalder 1994: 19). The analytical lens of historical ecology thus integrates environmental and human processes—be they within or between different classes and social groups—and examines resource utilization and their impact on a multi-scalar landscape.

Following Ostrom, I distinguish in this chapter between common-pool resources and the common property regimes that comprise the political or institutional level of governance (1991). These two elements in tandem constitute the larger system referred to here as commons. Common-pool resources are those materially defined, 'natural' resources that may be subtracted from or extracted. Common-pool resources refer to a physical entity, such as pastures or forests, fisheries or national parks that may be shared and used collectively, rather than only by individual private owners. On the other hand, common property regimes are a larger set of ownership and user rules that are the social means for determining how common-pool resources are managed and handled in common. Research on commons typically centers on how common-pool resources are used, and examines the interactions and relationships between people that are mediated through common property regimes. I posit that it is difficult to understand common-pool resource use or misuse without a more holistic assessment of the common property regimes that govern these resources and the people that utilize them. In the example of the Baigorri Valley that I turn to in the next section, commons over time formed a social, economic, and ecological landscape that serves as an important medium for interactions within and between groups.

When Garrett Hardin published 'The Tragedy of the Commons' in 1968, his theory of the commons rapidly caught the attention of agronomists, economists, geographers and anthropologists. In his seminal article, Hardin described a situation in which common-pool resources may be exhausted or destroyed by individuals tempted to pursue their own interests to the detriment of other users and the broader social collective. Although one may critique Hardin's conclusion that freedom in a common property regime brings ruin to all, or his conflation of open access regimes with common property regimes, he nevertheless provided scholars with an initial theoretical framework where human cultural variables and environmental factors intersect. Analyses of commons may also be problematic because there are few well-documented and detailed examples of common property regimes that have endured over the long term, which would allow researchers to better ascertain the reciprocal influences between humans and the environment (Stevenson 1991). I present the Baigorri Valley as an illustration of how a deep historical perspective can help elucidate the development of a symbiotic link between human activities and the resources available in their environment.

Common-pool resources include 'a class of resources for which exclusion is difficult and joint use involves subtractability' (Feeny et al. 1990: 4). In other words, control of access to common-pool resources can often be challenging if not impossible, and if a group of individuals exploits the same resource, they inevitably affect other users' potential to use that common property resource. Common property regimes are normally found in situations where it is difficult to completely exclude a subset of individuals from utilizing a certain resource, such as a tract of graze land or a stand of timber (Ruttan 1998). First, control over common-pool resources must be endorsed by a government entity or by community consent. Second, there are also usually mechanisms or rules for accessing common-pool resources to curtail overexploitation and to manage their use. For this, a community collectively decides upon and implements rules to prevent overexploitation or depletion of these common-pool resources. In this sense, a common property regime is not the chaotic scene envisioned by Hardin, but a structured arrangement among members of a community wherein rules are established and developed. These rules are characteristically a set of social norms governing people's responsibilities and their use of common-pool resources, but may also include ways of enforcing these rules and sanctions for breaking them. In this fashion, common property regimes play a central role in community life not only by providing a foundation for economic and ecological well-being, but also because the rules provide a means to regulate social tensions and competition over shared resources.

In addition to the importance of rules governing use of common-pool resources, the changing role of sociopolitical institutions is also one of the focal points of historical ecology. Such institutions are central to the use of common-pool resources since these entities may sanction 'the conventions that societies establish to define their members' relationships to resources' (Gibbs and Bromley 1989: 22). Common property regimes are thus characterized by a set of accepted social norms and rules governing access and use of resources, and include official sanctions set by institutions for those who abuse these rules. This type of property regime demonstrates a capacity for dealing with disruptions and sudden changes, and it is likely to minimize disputes and competition over resources and decreases the chances of abuse (Baden and Noonan 1998). Research on the commons must inevitably examine the types of relationships that individuals have with particular common-pool resources concerning their entitlements, responsibilities, and obligations (Dietz et al. 2003).

Common-pool resources in the three Basque Provinces in France may be collectively owned by individual villages, as in the province of Labourd. Common-pool resources may also be jointly owned and managed by multiple communities, which are oftentimes located within the same valley, such as is the case in the provinces of Lower-Navarre and in the case study of Xiberoa explored by Meredith Welch-Devine in this volume. In these two provinces, common-pool resources frequently include both mid-range graze lands in proximity to the villages, as well as higher altitude pastures for summer grazing—both landscape elements being crucial to farmers' success. However, the mountain pastures that are the principal common-pool resources for farmers can potentially place individuals' activities at odds with the interests of the local communities, and even those of the nation due to the proximity of the international border in the Basque region. In the following section, I examine how common-pool resource use has played out in the Baigorri Valley of Lower-Navarre over the past several centuries. We explore the role that local institutions and other social actors have had in mediating tensions over resource use by devising governance rules for the Basque commons.

Historical development of the Commons in the Baigorri Valley

Commons in the Baigorri Valley are by their very nature a contested, even threatened, space, in large part because of the contentious interactions and competitive relationships between humans utilizing common-pool resources over time. Commons in the Basque region have persisted for centuries in spite of numerous attempts to enclose, privatize, or limit use of common-pool resources. The Baigorri Valley was recognized as part of the territory ruled over by the king of Navarre as early as the 13th century in the Fors et Costumes du Royaume de Navarre (Cavaillès 1910). This document posited the rights and responsibilities of inhabitants in the Kingdom of Navarre, explicitly referring to the Baigorri Valley, and formally recognized the Cour Générale, an institution that primarily regulated land use issues in the community.

The B...