1 The World of Writing

‘‘Don’t believe people who tell you that writing is easy’ Alex Paton1.

The aim of this book is to get you writing and published. If you have not written already, use it as a starter kit, to find out what demands this crazy ambition will make, what rewards it will give, and how you can proceed along the path of getting your kicks from seeing your name in print. If you are one of those whose by-line already appears as regularly as long words in a management memo, don’t stop reading. This book is intended to reinforce your addiction, clarify your thoughts – if only through disagreeing with some of mine – and improve some of your skills. If there are any writers who insist that their work can never be improved, I would say to them, now is the time to give up and perfect something else.

This book does not offer a magic formula for making the writing process easier: I am afraid that I take the Calvinistic view that the value of an activity increases in proportion to the anguish that goes into it. However, it should give you a better chance of reaching that delightful state of ‘having written’, which, after food and sex, appears to be one of life’s greater satisfactions.

Some argue that good writers are born and not made, and that writing skills cannot be taught. I disagree. There is an element of talent, and some have a greater capacity than others to analyze situations, order thoughts, and use telling words and phrases. Such people can still be encouraged to do things better, while those apparently ‘less talented’ can be shown how to find marketable ideas, discipline their thoughts, develop an effective writing style and deal competently with editors. It is largely a question of attitude and confidence: ‘...very few people are incurably bad writers by nature, just as very few are congenitally diseased or deformed’2. In the unlikely event that you never get published – though I should make it clear that there is no money-back guarantee with this book – you should find that your writing will have improved, and that you are communicating more effectively with patients and colleagues. You may not be famous, but you should have more time and less aggravation.

All professionals – and health professionals are no exception – tend to write in their own private language. This excerpt from a medical journal gives the flavour:

‘Therapists rely heavily upon intuition, in the absence of any theory with sufficient explanatory power, to identify and follow recurring sequences of interpersonal behaviour which are seen when family members interact and to understand and predict how and when change in beliefs and behaviour may come about. An intuitive understanding of how to keep in communication with each member of the family is guided by a personally selected blend of congenial concepts which predict how change will come about.’

Cynics will argue that professionals encourage this private language because it promotes their own importance. (Has anyone else noticed the positive correlation between the length of words in a legal document and the level of fee?) With doctors, however, there is a more prosaic reason: from the age of 16 they are taught in the language of science. This puts the blame neatly on the education system.

Here I must distinguish between technical/ scientific language, which has its uses, and jargon, which has none. Often this is a question not of which words you choose, but of which audience you are addressing. The term ‘myocardial infarct’ gives a clear explanation to a fellow professional; to a patient, however, it is nonsense.

Jargon is not the same as gobbledegook, which is the use of long words and loose constructions which impress the writer but confuse the reader. Thus: It has been observed that residents of domiciliary units constructed of a brittle and transparent nature are ill-advised to project into orbit small projectiles of geological origin instead of People in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones. As Brendan Hennessy writes: ‘Gibberish or gobbledegook is likely to happen with professional people not used to writing for large audiences. They think the language of writing is altogether different from the language of speech; that, metaphorically, you dress in formal clothes to do it and choose a heavy pen’3. Phrases such as Does this fit in with your perceptions? and Serious long-term medication is herewith predicated are nothing more than a pompous and obscure way of saying Do you agree? and You will have to take the pills for the rest of your life. Yet such atrocities abound.

Scope of the book

The first surprise of the book may be that discussion of the use of language does not appear until Chapter 7. This is because the secret of successful writing hides below the water-line, at the preliminary stages of choosing the topic, the market, the research and the plan. Success depends on an even more basic question: should you be writing anyway? The next chapter, therefore, focuses on you as a writer. What do you expect to get from your labours? What can you offer, or – more important – not offer? How much time can you make available? Asking these questions and setting realistic goals from the answers is the surest way to long-term satisfaction.

These goals cannot be achieved in a vacuum, and Chapter 3 explains the world of publishing. If you want to become a good writer – which I define as someone whose words are regularly published with no substantial alteration – you must be able to answer three questions. What opportunities does the market offer? How does this market operate? And what is your place, as a writer, in it? Without this knowledge, any writing – however good the writer believes it to be – will remain undirected and unpublished.

After this brief foray into personality and product, the core of the book (Chapters 4-8) goes through the process of writing a feature article. These are articles of 600-2,000 words, which combine facts with comment. They are not scientific papers, nor are they news stories, which are shorter, factual items. I do not apologize for choosing this particular genre because many of the skills you will need for writing feature articles are essentially the same as you will need for other types of writing, and can be transferred easily. I have divided these skills into five main stages:

getting the brief,

collecting the material,

planning the article,

writing the article, and

doing the revision.

Some established writers may argue that their work goes straight into print, even though they do not follow these steps. That is not the point. I do not advocate ‘writing by numbers’, nor do I expect that those who ignore this process will be writing for the waste-paper basket. These stages are an attempt to bring order to a complex process, and to provide a framework which will ease nervous beginners into their first written article.

Once you have written your article, you must brace yourself for the next step, which is getting your article accepted. Editors are notoriously difficult people and the writer’s path to publication is paved with cracked stones. Many of the problems stem from stereotyping: editors think that their contributors are arrogant and greedy while contributors think that their editors are greedy and arrogant. Chapter 9 proposes some solutions to this problematic relationship.

The final chapter will explain how you can develop your skills, get further training and, perhaps, turn to writing as a full-time career. The appendices list further reading, professional organizations, training opportunities, a code of ethics, a bluffer’s guide to useful terms, and a selection of sub-editing marks.

Two basic principles

Two themes recur. The first, which has already surfaced, is that the actual writing, when empty coffee cups and angst pile up, is a relatively small part of the process. The real work, on which the success of an article depends, is done at a much earlier stage. Hence the importance of planning, of knowing what you are going to say, to whom and how. If you do this, you increase the chances of making your article work, and, incidentally, you will probably find that you have conquered writer’s block, that demoralizing time when you spend long hours staring at a blank page or empty screen.

The second recurrent theme is that all successful writers share a particular attitude. Five elements are needed for successful communication to take place: a communicator (writer), a message (article), a receiver (reader), complete understanding by that receiver, and some kind of feedback (Figure 1.1). Most writing fails because it is written with the writer – and his or her superiors – in mind, or because the writer is over-concerned with the nuances of the message. Successful writers will view the transaction from the reader’s point of view. This means putting your own needs out of your mind, and, if necessary, simplifying the message so that it can be understood. In other words, messages must be put across, not just put out, and the ultimate test is whether the reader understands. This point can never be too highly stressed.

Cynics will argue that the last thing we need is more writers in general and more medical writers in particular. We live in a world which is rapidly becoming immersed with bits of paper: the average professional will have dozens of pieces of paper landing on their desk each day. For doctors, with scores of unsolicited publications – not to mention instructions from authorities, learned articles from colleagues, letters to and from patients – clogging up their mailboxes, this must be much more.

Figure 1.1 Elements of communication

As we shall see in Chapter 3, the quantity of publications is generally beyond the individual’s control. Yet the question of quality is not. A society that claims to be rational and democratic must support the free flow of ideas and information. The better these ideas and information, then the better our chances of moving forward, or at least not moving back. We will be presented with facts on which to base our opinions, and arguments that will stimulate our thoughts. At the same time we will be, in the broadest sense, entertained.

Doctors and other health workers have a duty to take part in this process. Their concern is with sickness and health, which is literally a matter of life and death to us all. They are one of the most highly trained groups of professionals, and have an education, outlook and experience that is extremely valuable. A world of ideas to which doctors did not contribute would be lopsided indeed.

Key points

1. This book assumes that writing skills can be taught. It will take the reader through five stages of writing a feature article: (a) setting the brief, (b) planning, (c) research, (d) writing and (e) revision.

2. Two themes will recur, (a) Writing is a small part of the process and planning is vital, (b) The ultimate test of good writing is that it is read and understood by the chosen audience.

2 Understanding the Writer

‘What you must on no account do is wait for inspiration’ – John Braine4.

We all know someone who nearly wrote a novel. It would have been marvellous if they could only have found the time. Yet the only accomplishment that marks out a writer from the rest of the world is that the writer has made time. Whether the writings are published is beside the point.

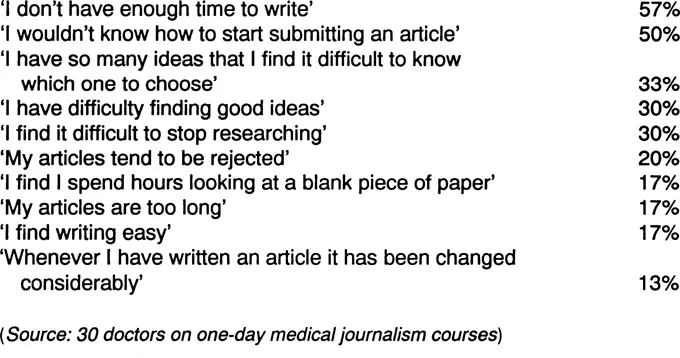

Figure 2.1 Problems faced by writers

A questionnaire given to 30 doctors attending courses on medical journalism showed that more than half felt that their main problem was finding time (see Figure 2.1). Obviously this reflects the priorities they have chosen, but it is not the whole story. Any activity slips quickly down the list when you are not sure how to get started. This means that, if you are new to writing, you should not take yourself off to a darkened room ‘to write’; you will end up with very little apart from balls of paper and depression. Instead, invest some time in asking yourself some basic questions. You will not need a desk to do this; scribbling on the back of an envelope in odd fragments of the day will do. Once you have answered these questions, you should be able to fit your new activity into your schedule.

Know what you want

Thousands of people write and thousands more try to do so. The rewards seem to be high. Admirers will cherish you for your wit and wisdom. Lucrative commissions will flow in and your bank manager will be amazed at the transformation of your finances. Your local paper will be full of photographs of your receiving prestigious awards for services to medical publishing, and conference organizers throughout the world, and particularly in the Caribbean, will send you first class return tickets for yourself and your partner. You might even make it onto Question Time or Any Questions.

Inevitably there is a down-side. Writing is in black and white. It will commit you, and those that you are writing about, to your statements in a way that speaking does not. Your opinions will often be seen to be critical, even if you didn’t intend them to be, or, worse still, had taken great pains to disguise them. If you report the views of others, they will almost certainly accuse you of oversimplification. And, if you become a published author, others will feel uncomfortable because they did not do it first. The professional classes are not immune to jealousy.

It may not end in tears, but it could spoil a good meal. I remember one formal dinner at which the guest speaker, a distinguished medical writer, was ‘buttonholed’ by an eminent researcher, and publicly attacked for allegedly ruining the reputation of a colleague several years before. At least he was told of his offence, even though he couldn’t remember it. Grievances tend to dwell in the minds of...