eBook - ePub

Releasing Resources to Achieve Health Gain

This is a test

- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Releasing Resources to Achieve Health Gain

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In every developed country, health care managers, clinicians, purchasers and providers are having to extract greater output from cash-limited resources. This book reviews a wide range of areas of current concern together with the practical experience of those responsible for improvement and change. The opportunities and pitfalls they identify should stimulate innovation and fresh ideas in those faced with similar situations.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Releasing Resources to Achieve Health Gain by Christopher Riley, Morton Warner, Amanda Pullen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Public Health, Administration & Care. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Focusing Clinical Activity on Outcomes

1

Overview

Richard Lilford

Introduction

About five years ago, a structured review on the effectiveness of homeopathic treatment appeared in the British Medical Journal1, apparently arousing very little interest. Releasing resources to achieve health gain must rely heavily on structured reviews, but the data assembled in a structured review require critical appraisal. That on homeopathy covered about 80 studies, over 60 of which were randomized clinical trials, mostly showing that the homeopathic medicine worked. At first sight, therefore, homeopathy has a proven effectiveness and henceforth people should purchase this inexpensive and effective treatment. This chapter will deal with how to sift and analyse clinical evidence and really make sense of it: it will show why people are right not to purchase homeopathy at this time.

The epistemology of clinical research

Clearly, using the most effective treatments enhances allocative efficiency, as discussed on pp. xxiii to xxxiii. How can knowledge be used to improve the cost-efficiency of the Health Service as a whole? The study of knowledge began in the time of Aristotle, but enthusiasm for good clinical evidence was given new impetus by Sir Austin Bradford Hill2, probably the most deserving person never to get a Nobel prize. He was the first person to do a modern randomized trial, back in 1948, on the use of streptomycin for treatment of tuberculosis. His other famous contribution, with Richard Doll, was the discovery that smoking causes cancer.

Clinical trials, Bradford Hill pointed out in the 1940s, are only required where the effects of treatment are not obvious. Some treatments introduced in his day had quite obvious beneficial effects. Then people with untreated meningococcal meningitis died almost invariably. With the advent of penicillin, they hardly ever died. Here Bradford Hill would be the first to say that a clinical trial would not be needed, but most modern treatments have much smaller, less obvious gains, detectable most reliably by clinical trials. The results of laboratory experiments alone are insufficient to show the effects of clinical interventions on humans. For example, prophylactic drugs to stop a disturbance in the heart rhythm are not effective after heart attack, while blood thinners are. Yet cardiologists, before trials were conducted, favoured drugs for rhythm and eschewed blood thinners.

The idea of randomized trials started from using clinical studies as a source of evidence, then the notion of control groups was added and finally with Bradford Hill randomized assignment to control and treatment groups was introduced to overcome any bias from allocating people with a different prognosis to each group. The concept of the appropriateness of randomization has been backed tip by empirical studies. For example, one showed that randomized studies, as a general rule, show smaller gains than alternative designs3.

In the early days of the health reforms, the author argued that health commissioners should have a role in purchasing and commissioning the right kind of research4. Health-care purchasers in Yorkshire pay money into a central fund, under the control of the Regional Research Director, who is then able to purchase access to important clinical studies. In this way the NHS can make its contribution to the international research effort, to help clarify what is effective care. It is appropriate that such studies should be of high quality and this will often involve randomization. It is also important that they are ethically sound.

Ethics of clinical trials

Ethics of principle is about whether one should do it in the first place. Here the issue is ethics of procedure – how one should do something, perhaps the more substantive issue.

The basic tenet for the ethical conduct of a clinical trial is captured in the word ‘equipoise’. Equipoise means that observers are completely unsure as to which of two treatments is better5. It is sometimes referred to rather loosely, for example by Richard Peto, as the ‘uncertainty principle’. But ‘certain’ is rather a vague word in this context because it leaves the degree of certainty undefined. The word ‘equipoise’ means that it is thought equally likely that treatment A and treatment औ will bring most benefit. The relative odds or relative risk of the two treatments having different effects is perceived as one in two, or one to one. A clinician should be at or very close to this point of equivalence before entering a patient in a trial in clear conscience, assuming that the two treatments under comparison are generally freely available.

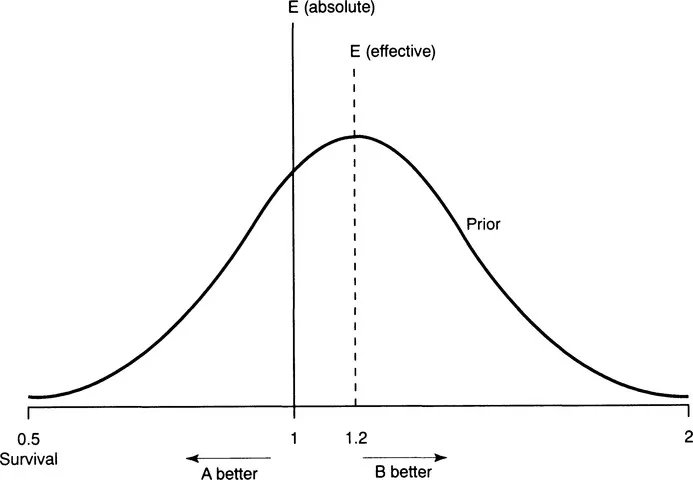

Equipoise may be represented as a curve, the peak of which is the most likely result. Thus, as a potential (hypothetical) result becomes more extreme, so the likelihood of that result occurring declines. These likelihoods are reflected on the ‘equipoise curve’.

Of course the situation is more complicated than this, because treatments are not simply better or worse. In some cases, a treatment has known and obvious side-effects. In this case, equipoise is not that there is no absolute difference between the treatments, but rather that there is a difference sufficient, but only just sufficient, to make up for the known side-effect of the treatment with greater known side-effects. Imagine a clinician who thinks that it is more likely than not that treatment B is better than A, but B has a known severe side-effect. Imagine, then, a patient who would demand a 20% improvement of survival to make the side-effects worthwhile. A clinical trial would then be ethical if a 20% gain in survival was perceived by the clinician to be the most likely result andii the patient would be indifferent between the two treatments at this gain in survival. Equipoise around ‘no difference’ between treatments is called ‘absolute equipoise’ and ‘no difference’ around the effect which precisely compensates for the more invasive treatment is called ‘effective equipoise’ (Figure 1.1).

While the main obligation of a purchaser is to maximize the health – broadly defined – of a community, the primary obligation of the clinician is to the individual patient. To understand the ethics of clinical trials, it is necessary to draw the distinction between the obligations of clinicians to individual patients and those of purchasers to patients in general. The individual clinician-patient pair should be in effective equipoise for trial entry, while a purchasing authority (or funding agency) need ensure only that clinicians as a whole are equipoised – ‘collective equipoise’. The requirement for patient-clinician couples to have effective equipoise places a constraint on clinical trials because the physician must think that the most likely treatment effect coincides with that which the patient would require. That surely must be a fairly unusual clinical scenario. Many completed clinical trials, if judged by this criterion, would be declared unethical. The famous trial of folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects may be difficult to defend on this basis.

Figure 1.1 Equipoise curve. This shows the likelihood of different results as seen by a doctor or group of clinicians before a trial. E (effective) is the magnitude of effect that would make the side-effects of a treatment with greater side-effect worthwhile, in this case treatment B. E (absolute) would represent equipoise around a most likely effect of no difference either way

However, a distinction should be drawn between treatments like folic acid which are freely available and treatments such as ECMO (extra corporeal membrane oxygenation – an artificial lung), which is not in routine use. A group of physicians in Harvard decided they would like to do a trial of this very expensive and invasive treatment. The randomized trial started in effective equipoise; they thought the benefits the equipment might offer were about equivalent to what their patients might demand of them. However, the first patients studied did much better with ECMO, and they stopped the study. They have been criticized for this, because the questions provided had not been answered in the usual scientific sense, but they were right to stop the trial when they did; they had access to the equipment and to enter patients further would violate the principle of equipoise, because they believed that ECMO was effective.

A more extensive trial of ECMO is taking place in the UK, with four designated treatment centres. The doctors will offer the parents of babies with lung failure a choice between conventional treatment or entry into the randomized trial. They are right to offer randomization, even if they perceive benefits greater than those required for effective equipoise. This is because access to ECMO is only available through the trial. The people who are funding that trial are also right to restrict access in this way and the Government is quite right to restrict ECMO in this country until a clinical trial can show whether the amount of benefit that it gives is sufficient to justify the cost. There is enough uncertainty to make the trial ethical from the perspective of those providing care – they must help clinicians and society at large to glean evidence about new treatment ethically by evaluating new technology in trials.

Combining trial results

How do these ethical considerations affect our interpretation of data? The first question is how do we know the effects of treatments? Interpretation of clinical evidence depends on three things: prior perceptions of clinicians of the likely effects, precisio...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- Releasing resources overview

- Part One Focusing Clinical Activity on Outcomes

- Part Two Acting Now to Prevent Later Problems

- Part Three Doing Things Differently

- Index