- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Korean Literature

About this book

This study examines the development and characteristics of various historical and contemporary genres of Korean literature. It presents explanations on the development of Korean literacy and offers a history of literary criticism, traditional and modern, giving the discussion an historical context.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Korea is a country with a rich literary tradition, and literature plays an important role in Korean society. More than 6,000 collections of writings by individual writers from the thirteenth to the nineteenth centuries are extant, despite numerous wars and natural disasters. Korea has a rich oral tradition of legends and folk songs. Despite the growth of film and television in contemporary Korea, most Koreans have a strong interest in literature. For example, Korea leads the world in the per capita publication of books of poetry. An awareness of this is important if we are to have a balanced understanding of the value of Korean literature, as well as of the Korean people and culture.

There are two main reasons for the great body of literary works and the enthusiasm for literature on the part of the Korean people. The first is the original Siberian culture, reflected in geometric patterns on earthenware, that the people who moved from northeast Siberia into Manchuria and the Korean Peninsula brought with them in ancient times. These ethnic groups, who became the Korean people, had â culture distinct from the Chinese culture of the time, as shown by their love of song and dance. According to ancient Chinese records, Koreans gathered together to dance and sing for days on end in ceremonies dedicated to the gods who protected the kingdom and provided good harvests. These same records also show that Chinese visitors were surprised by how much the people of Koguryŏ and Chinhan enjoyed music and dance in everyday life. Although there is no such thing as a permanent national character, the importance of music and dance in the lives of Korean people today can be traced to these ancient traditions.

The second reason is the strong Confucian tradition that prevailed in Korea from the founding of the Koryŏ Dynasty in the tenth century to the end of the Chosŏn Dynasty in the nineteenth century. This tradition valued literary culture over all other forms of cultural activity. Except for the roughly seventy years of military rule from 1170 to the middle of the thirteenth century, Korea was governed for ten centuries by Coniucian literati. To train and select literati for public office, educators placed emphasis on literary training based on the study of Confucian classics and especially the composition of prose and poetry. This type of education was particularly dominant during the Chosŏn period, which lasted from the fourteenth to the nineteenth century. Unlike Europe and Japan, which were ruled by knights and samurai, respectively, Korea was ruled by scholars and writers, who used literature to establish and maintain their dominance in society. This tradition continues to exist today, because most Korean writers and poets feel a special sense of duty to uphold social justice, rather than viewing themselves as autonomous artists. The importance of literature and of writers in resisting Japanese imperialism during the first half of the twentieth century and in opposing military dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s reflects this sense of duty.

These factors not only explain the importance of literature in Korea but also form a usefixl paradigm for understanding its contrasting aspects.

Korean literature has two main characteristics: emotional exuberance and intellectual self-control. The former comes from the shamanistic energy rooted in Siberia, whereas the latter comes from the tradition of Confucian rationalism. Depending on the times, these characteristics merge or conflict with each other. The overall conflict, compromise, and equilibrium between these two characteristics remains central to Korean literature today.

The unity forged by the spatial and temporal meeting of diverse cultural factors that make up Korean literature is evident in the following example. Contrary to some prevailing foreign views, Korean literature is not an offshoot of Chinese literature, and, of course, it differs from Japanese literature. Korea transmitted many cultural achievements to Japan from ancient times to the nineteenth century. Although it has much in common with China and Japan, Korea has a unique culture that developed through history as an independent state with its own social structure and way of life. This unique culture is also reflected in literature.

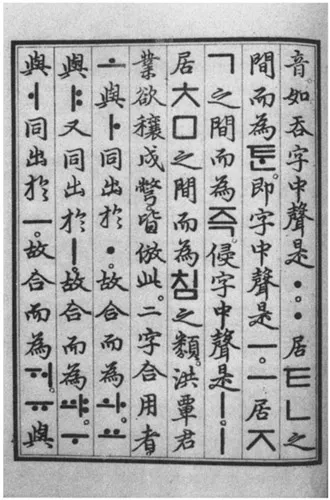

As Cho Chihun argued in his Introduction to the History of Korean Culture (Hanguk munhwasa sasŏl, Cho Chihun chŏnjip 6,1973), Korean culture developed from a Siberian cultural base, borrowing its writing system and Confucianism from China, and Buddhism from India. With its Siberian roots, Korean culture has fundamentally different origins from Chinese culture and differs sharply from Japanese culture, which has been influenced by the culture of the Pacific islands. Linguistically, the Korean language, a member of the Altaic family of languages, is totally unrelated to the Chinese language, which belongs to the Sino-Tibetan family. In the first half of the fifteenth century, King Sejong and the scholars he assembled created a phonetic writing system known as hangŭl. This system differs greatly from meaning-based Chinese characters. Hangŭl also differs significantly from the Japanese syllabic system of writing known as kana, because each hangŭl letter represents a distinct phonetic element rather than â syllable composed of set sounds. How Korean literature interacted with common literary traditions in East Asia while developing its own character is an interesting theme in the study of its history.

Page from Correct Sounds to Instruct the People (Hunmin chongûm)

Another important topic of research is the influence of Western culture on East Asian traditions in Korean literature. China came into contact with Western culture relatively early, with the Silk Road, and Japan had limited contact with the West through trade with the Netherlands beginning in the seventeenth century. Korea, however, remained closed to the outside world, except for relations with neighboring China and Japan, until the end of the nineteenth century. With the strengthening of the closed-door policy in the late nineteenth century, Korean became known as the “Hermit Kingdom.” Thus, when Korea was forced to open itself to the outside world at the end of the nineteenth century, the country experienced a shock far greater than did China or Japan. Although the term “literary revolution” was used in the May 4 Movement in China, the revolutionary change in Korean literature at the beginning of the twentieth century was much more sudden.

In the course of these drastic changes, traditional literary forms, structures, and aesthetic standards collapsed rapidly. New literary stimulation coming from the West, Russia, and Japan contributed to the development of a new literature. However, despite this enthusiasm and interest, Korean literary traditions remained influential. Korean literature in the twentieth century has been dominated by a desire to break away from the past on the one hand and, on the other, the need to establish itself in the face of strong foreign influences as a legitimate national literature rooted in Korean culture.

Amid the interaction between these two conflicting trends, Korean literature since the early years of the twentieth century has been searching for a new balance between literary imagination and sensibility. The historical movement to create a new paradigm in Korean literature based on long tradition and change is another important theme of research on the subject.

The common view that it is possible to understand the folkways, worldview, aesthetic sense, and emotional outlook of a group of people through the literature they create and develop is particularly applicable to Korean literature. The social energy of the literary outpouring that encompasses the ancient tradition of poetry and song, the respect for literature during the Koryŏ and Chosŏn periods, and severe conflicts since the nineteenth century reveal much about the Korean people past and present. Thus, the study of Korean literature becomes a rewarding jounley on which we discover the dreams and the fears, the glories and the defeats, and the joys and the sorrows of the Korean people through the ages.

2

The Extent of Korean Literature

Before attempting to understand the unique characteristics and overall outline of Korean literature, we need to define its extent geographically and through time. By “Korean” literature we refer to the entirety of literature written by ethnic Koreans, from ancient times to the present. Contemporary Korea is the present-day result of past periods of expansion and contraction, division and unification; any overall history of Korean literature must take into account this history of evolution and change. In addition, we need to consider the place of the major traditional types of Korean literature, which are rooted in the social structure and cultural background of Korean society before the nineteenth century, and each of which differed in its mode of expression and transmission: oral literature, vernacular literature in hangŭ, the Korean alphabet, and literature in classical Chinese. We also need to have a basic understanding of the defining characteristics of these types of literature, as well as of the relationship among them.

There is little disagreement on the geographical extent of Korean literature: Korean literature can be defined broadly as the entire corpus of literature developed by Koreans in places where they have lived throughout history. This definition does, however, leave us with the issue of how to treat the literature of Koreans living abroad, and the geographical and cultural borders of Korean literature before the rise of the three kingdoms of Koguryŏ, Paekche, and Shilla. Whereas the literature of many nations reflects a mixture of ethnic groups, languages, and cultures, the literature of Korea is closely linked to the history and culture of the Korean people. The first stage in the development of Korean literature is the period from ancient times to the establishment of a proto-Korean state, during which various ethnic groups moved east and south from central Asia into Manchuria and then into the Korean Peninsula. As a Korean people began to emerge from the gradual integration of ethnic groups, the literature of those groups in time became what we could call “Korean literature·” It then developed flirther throughout Korean history: the Three Kingdoms, Koguryŏ (37 B.C. to A.D. 668), Paekche (18 B.C. to A.D. 660), Shilla (57 B.C. to A.D. 668); the era of the Unified Shilla Dynasty in the South (A.D. 668-935) and Palhae in the North (A.D. 698-926); the Koryŏ Dynasty (918-1392); the Chosŏn Dynasty (1392—1910); and the modern and contemporary eras. Ethnic Koreans have also lived outside Korea throughout history; their literature should be included on the fringes of the history of Korean literature, because their cultural roots are in Korea.

In order to map the various types of literature, which are defined by their mode of expression and transmission, in the overall context of Korean literature, we first need to consider the complex cultural history of Korea. Among the three main types—oral literature, vernacular literature in hangŭl, and literature in classical Chinese—oral literature and literature in classical Chinese have been the subject of much controversy in Korean literary criticism and historiography.

Oral Literature

Oral tradition is clearly part of Korean culture; nevertheless, doubts about its legitimacy as “literature” have arisen. The argument that the oral tales and stories that have been passed down to us from the formative eras of Korean culture are not a legitimate literary form is based on the Korean etymology of the word literature, which derives from the concepts of “letters,” or “that which is recorded in writing.” Thus it is argued that literature is basically written text. Accordingly, such tales and stories are excluded from the main body of Korean literature and are classified instead as “protoliterary linguistic structures,” or “pseudoliterature.“

In the end, however, this argument fails to be persuasive. Just as spoken and written forms of expression are subcategories of language, so literature is an art developed through the use of language, regardless of whether it is written or oral. For this reason, literature in its various forms has continued to develop throughout human history. If it were logical to limit the field of literature to “works of art in writing” throughout all historical eras, then we would simply not be able to classify oral lore as literature. Hence, using the adjective oral to qualify literature would be impossible. If we were to consider only written literature as such, then we would be asserting that there had been no literature before the development of written language. Furthermore, we would be arguing that the common people in most societies, who remained illiterate well after the development of writing, were not participants in the creation of literature. This argument would also apply to various ethnolinguistic groups that did not develop a written language. Needless to say, this argument fails, because it denies the basic human need for aesthetic expression through “literature.” To do so—on the basis of little more than a prejudice for the modern and the contemporary—would be to diminish the vast amount of literary creation that has evolved and gained inspiration from oral transmission since the beginning of human civilization.

Of course, we cannot deny that important differences in the function and characteristics of literature have arisen because of the method of transmission. The difference between oral and written literature is not only limited to the superficial issue of whether it is written down or not; rather, it has a direct bearing on the great diversity of forms of literary creation. Moreover, making a distinction between historical facts and fiction is difficult because of the nature of the transmission of oral literature. We have only scattered fragments of evidence, found in documents or songs and tales that have come down to us from the distant past, as primary sources. For this reason, we cannot, however, conclude that oral literature is not literature, or that it should be treated as supplementary material in the study of written literature. Oral literature is of critical importance in a comprehensive historical study of not only Korean literature but of any literature.

Problems with the Inclusion of Literature in Classical Chinese

The inclusion of literature written in classical Chinese within the body of Korean literature has been a controversial cultural issue, because classical Chinese represents a foreign language. Those who argue against the inclusion of this literature base their arguments on the non-Korean origin of Chinese characters: Korean literature is vernacular literature written in hangŭl that deals with the experiences, sensibilities, and thoughts of the Korean people; therefore, literature that makes use of Chinese characters and Chinese literary forms cannot be considered Korean literature. This argument first appeared in the second decade of the twentieth century and was firmly established as orthodoxy by the end of the 1920s (Yi Kwangsu, Concepts of Korean Literature [Chosŏn munhak ŭi kaenyŏm], 1929). This thinking continued to exert a strong influence on the definition of Korean literature well into the 1950s.

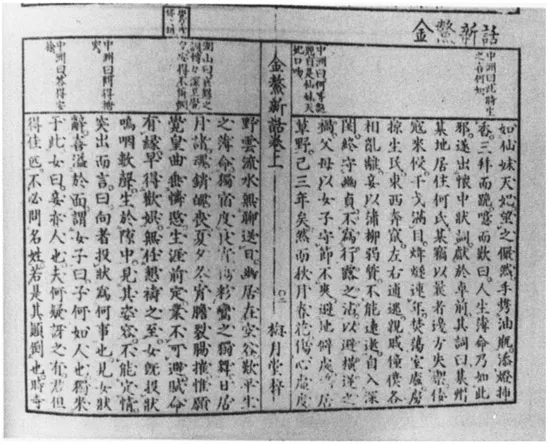

Page from Tales of Kŭmo (Kŭmo shinhwa), written in classical Chinese

Before discussing the validity of this argument, we need to understand the historical background of the early twentieth century. The Confucian ideology that had served to legitimize the rule of the Chosŏn kings was unable to respond to the upheavals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Korea came under Japanese colonial rule. Confucian heritage was criticized in Korea simply because the Chosŏn Dynasty, which had based its legitimacy on Confucian philosophy, collapsed at the end of the nineteenth century. Under the oppression of Japanese colonial rule, the attempt to assert Korean cultural identity and pride was built on the premise that only literature written in hangŭl should be considered real Korean literature. The traditional belief that literature in classical Chinese was more elegant and prestigious lost its legitimacy amid the dramatic changes in Korean society in the early twentieth century. Thus the argument that literature written in hangŭl should define the extent of Korean literature became the established orthodoxy during this period.

Though we cannot overlook the grave historical circumstances that gave rise to this idea, the elimination of literature written in classical Chinese reflected a narrow-minded and moralistic analysis of Korean cultural and literary history. Even if we concede that language is the most important aspect of literature, this importance is related to the cultural context of the period and should be understood in this light. In addition, Chinese characters and classical Chinese literary forms are not exclusively “Chinese,” as some extremists on this issue have argued.

Here we need to examine the importance of classical Chinese as a common written language in East Asia (China, Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and the Ryūkyū Islands), which lasted well into the nineteenth century. Chinese characters are obviously Chinese in origin, but they do not necessarily reflect the spoken forms of the Chinese language. The term Chinese characters refers to the character-based writing system that developed in China from the Qin Dynasty (221—206 B.C.) to the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.—A.D. 250). Classical Chinese was a common written language in East Asia as Latin was in Europe in the Middle Ages, or classical Arabic was in the Arab world. Having become separated from the spoken language in China, classical Chinese spread to Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, where it coexisted with the indigenous languages of each nation. In these three n...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Translator’s Preface

- Author’s Preface

- Illustrations and Maps

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The Extent of Korean Literature

- 3. Language, Style, and Meter

- 4. Genres of Korean Literature

- 5. Literary Criticism

- 6. The Trade in Literary Works

- 7. Phases of Korean Literature

- Glossary

- Select Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Korean Literature by Hung-Gyu Kim,Robert Fouser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.