![]()

1 Bronze Age and Homeric warfare

Achilles vs. Hector?

Introduction

The Greek literary canon begins with a single, evocative word: rage (mēnis in Greek). Homer, if he indeed was a real person (we will come back to this point later), carefully chose “rage” to start off the thousands of lines of poetry contained in the Iliad, the epic account of turmoil in the Greek ranks arrayed before Troy, in the final year of the ten-year-long conflict we call the Trojan War. In so doing, Homer also started, for all intents and purposes, Greek literature, and

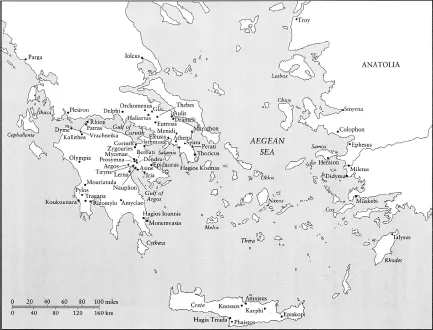

Map 1.1 Mycenaean sites in the thirteenth century BCE.

Source: from Readings in Greek History (2nd edition) by D. B. Nagle and S. Burstein (2014).

Map 1.1, p. 3. By permission of Oxford University Press, USA.

composed a work that had an incalculable impact on every aspect of Greek life, including, perhaps most of all, war. The Iliad, and to a lesser extent the Odyssey, the other heroic epic attributed to Homer, tell of great warriors in battle, men of the front ranks, or promachoi, who single out worthy opponents from the other side and fight to the death. Though supposedly telling of the Late Bronze Age – the canonical date for the fall of Troy is 1184 BCE – the Homeric epics were mined as sources for moral instruction, as well as tactical maxims, by the ancient Greeks many hundreds of years later.

In this chapter, we will consider how the rage of Achilles, the Iliad’s preeminent hero, and the battlefield struggles surrounding it, can inform us about the Greeks at war. What drove Achilles to fight, and to refuse to fight after growing angry at his commander? What were the military values held by the Homeric heroes? And how did the regular soldiers, the masses in the shadows behind great leaders such as Agamemnon and Odysseus, experience war? Without understanding the world of Homeric epic, we simply cannot understand the Greeks, least of all in the sphere of warfare. Before turning to epic poetry, we will first consider what actual Late Bronze Age warfare was like in the Greek world and broader Mediterranean region, and to what extent the Bronze Age is reflected in the work of Homer, who composed some 500 years after the fall of Troy. We will then explore the figure of Homer himself, and the world of his heroes, before taking into account how Homeric poetry was received by later generations of Greeks. The chapter will end with a reconstruction – as far as is possible – of a duel and subsequent pitched battle in the Iliad, at least in terms of how later Greeks could reasonably interpret it.

The Mycenaeans and war

The world inhabited by the Homeric heroes had a real historical context, whether or not this context is accurately reflected in the Iliad and Odyssey. In the Late Bronze Age (c.1600–1100 BCE), central and southern mainland Greece, and other spots around the Aegean Sea, including Crete and parts of Asia Minor, were dominated by a palatial civilization scholars call Mycenaean. This civilization gets its name from the important archaeological site of Mycenae, which commands the Argolid plain in the northeastern Peloponnese. In literature, Mycenae was the city of Agamemnon, the most powerful Greek king and leader of the expedition against Troy. The location of Bronze Age Mycenae was never in doubt, since its imposing walls had always been visible. Accordingly, when the impressive site was excavated in the late nineteenth century by the controversial archaeologist-cumtreasure-hunter Heinrich Schliemann, it was proclaimed to be none other than Agamemnon’s capital. Following this excavation, the entire Bronze Age civilization throughout Greece exhibiting the same or similar material culture as found at the site of Mycenae was dubbed “Mycenaean.” It is important to remember that, even though there might well have been cultural, diplomatic, political, and military contact between several of the great Mycenaean sites in the Aegean, it is unlikely that these people called themselves Mycenaeans, let alone were ruled by the literary Agamemnon and his peers. Nevertheless, the impressive remains of Mycenaean palaces, citadels, and tombs likely inspired the Heroic tradition in Greek culture, meaning that the Mycenaeans are significant for the study of Greek warfare. Moreover, we now know that the historical Mycenaeans spoke an early form of the Greek language (recorded in a script called Linear B), meaning that they were by definition Greeks. We thus begin our study with the Mycenaeans and their way of waging war.

One of the most striking things about the Mycenaeans is just how warlike they were. The civilization that inhabited the Aegean islands during the Middle Bronze Age in the centuries preceding the construction of Mycenaean palaces was comparatively peaceful, at least in terms of what material culture can reveal. The Minoans, as this earlier people was named by scholars after the mythological king Minos of Crete, ruled from large and lavish palaces in cities like Knossos on Crete, and decorated their walls with glorious frescoes, as can be seen most spectacularly at Akrotiri on the island of Thera, now called Santorini. The Minoans, who were not Greek, had wealth and culture to spare, but while there are suggestions that they might have engaged in some violent practices, including most disturbingly human sacrifice, military imagery is relatively lacking in their iconography.1 To be sure, the Minoans forged swords, portrayed warriors on some of their objects, and even, in the case of the frescoes preserved at Akrotiri, represented fearsome naval flotillas on their walls.2 But the sheer prevalence of weaponry and military imagery seen in the Mycenaean period simply was not there for the Minoans. Most tellingly, the great Minoan palatial centers were as a rule un-walled, meaning that the Minoans did not fear violent assaults from political rivals or marauders eager for plunder. These un-walled sites, particularly Knossos on Crete, might be due to the maritime dominance of the Minoans rather than an inherently peaceful nature, but whatever the case may be, the world of the Minoans does not seem to have been as violent and unstable as later periods in the Aegean would be. The Minoans were eventually replaced – defeated? – by the Mycenaeans, who were based on the Greek mainland rather than the Aegean islands. By contrast to their predecessors, the Mycenaeans were fixated on the image of the warrior, and their centers were eventually walled in the most impressive way possible.

In the 1600s–1500s BCE, the rulers of Mycenae were buried in lavish style in two “grave circles,” respectively called Grave Circle A, the later series of graves found within the fortification walls of a subsequent building phase, and Grave Circle B, somewhat earlier than Grave Circle A and now located outside of the walls. Schliemann’s discovery of Grave Circle A was an epochal moment in Mediterranean archaeology. Contained within these burials was a nearly unbelievable level of wealth, including the famous gold funerary masks of which Schliemann dubbed one the “Mask of Agamemnon” (despite being several hundred years too early for Homer’s Agamemnon). In addition to luxury goods, these rulers were buried with the status markers of great warriors, including swords, daggers, and even gold seals depicting scenes of combat and the hunt. Some of the stone stelai, or slabs, placed atop these graves depict images

Figure 1.1 The Mycenaean Warrior Vase, thirteenth century BCE.

Source: National Archaeological Museum, Athens (no. 1426). Photo credit: Scala/Art Resource, NY.

including riders atop chariots, the ultimate military status symbol in the ancient world. In addition to their wealth and status, those buried in the Mycenaean grave circles clearly wanted to identify with and advertise their participation in the warrior ethos. Later phases of settlement at Mycenae, roughly contemporary with the Trojan War, furnish examples of frescoes and other artistic media that demonstrate the continued importance of martial imagery. Several frescoes depict “figure-eight” type shields, while the celebrated “Warrior Vase,” found near Grave Circle A, portrays several warriors marching in a line, equipped with round shields and thrusting spears. Such imagery is virtually absent from Minoan contexts, indicating that the Mycenaeans were a decidedly more militaristic people.

In 2015, Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker, the directors of the University of Cincinnati excavations at Pylos, another prominent Mycenaean site in the Peloponnese, dominated by the “Palace of Nestor,” named after one of Homer’s heroes, discovered a remarkable tomb roughly contemporaneous with the Mycenaean grave circles. This so-called Griffin Warrior Tomb, named because of the stunning ivory plaque decorated with a griffin found within, might represent one of the earliest material examples of the Mycenaean eclipse of the Minoans. This tomb was the final resting-place of a single male warrior, who

Figure 1.2a–b The Combat Agate from the Grave of the Griffin Warrior at Pylos, fifteenth century BCE.

Source: courtesy of the Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati.

was buried with a plethora of weapons and armor, including a meter-long sword with a gold hilt and boar’s tusks for the type of helmet described in the Homeric poems, and a handsome collection of jewelry, metal vessels, and other luxury items. Most spectacular of the finds in the grave is an agate sealstone depicting a scene of combat in such remarkable detail that the sealstone and its imagery must have been especially significant for the warrior and those who buried him. Many of these items were of Cretan origin and design, suggesting that this warrior, who was most likely a prominent leader at early Mycenaean Pylos, took full advantage of the wealth of Minoan Crete, demonstrating that what the Minoans had once enjoyed without the need for fortifications or the promotion of an overt warrior culture were now the prerogatives of the type of warrior-kings that so impressed Homer and his Greek audience centuries later.3

In later, historical periods, we know that Mycenaean tombs were frequently used as centers of cult, the natural place to venerate the heroes who were buried in such lavish and militaristic style. Homer and his audience, therefore, could well have been aware of the Mycenaean funerary culture only revealed to the modern world by archaeologists not even a century-and-a-half ago. What must have impressed Homer’s audience most of all, however, were the remains of the walls of Mycenaean citadels that would have been still visible in the Archaic and Classical periods. Modern visitors to Mycenae are struck first by the sheer scale of the site’s walls, and the impossible size of their stones. The walls at Mycenae and other Mycenaean fortified sites, including nearby Tiryns, and Gla to the north in Boeotia, were built first in the 1300sBCE – a couple of centuries after the Grave Circles and the Griffin Warrior Tomb – suggesting that by that time the level of violence in the Aegean world had increased markedly. Today we call the type of masonry seen in the walls of Mycenaean citadels, characterized by large undressed stones arrayed in rough courses with small stones used to fill in gaps, “cyclopean,” since only mythical creatures like the Cyclops, made famous by Homer’s Odyssey, could possibly have worked with stones of such heft. The Roman author Pliny the Elder, citing Aristotle as his source, attributed such structures to the cyclopes even in antiquity (Natural History 7.56.195). These citadels were impossible obstacles for any potential enemies, since not until the late Classical and Hellenistic periods did ancient Greek armies develop effective siege tactics (though other ancient cultures, such as the Assyrians, did develop such tactics in earlier periods). Mycenaean walls can fairly be said to have been overbuilt, constructed taller and thicker than dictated by any purely tactical considerations. In addition to providing protection from enemies, Mycenaean walls would have been another demonstration of the superhuman power and wealth of Mycenaean rulers, a message directed at rivals and perhaps also at the rulers’ own people, living in far humbler dwellings outside and in the shadows of the citadel. Surely those who built such things, as Homer and his listeners might have reckoned, were far beyond the normal men and women of everyday experience. The common Mycenaeans too probably thought their rulers to be supermen.

In discussing the warfare of the Mycenaean world, it is crucial to keep in mind that the Mycenaeans existed in a broader eastern Mediterranean context.

Figure 1.3 The Walls of Tiryns, thirteenth century BCE.

Source: author’s photograph.

Elite Mycenaeans were influenced by the rulers of other, more powerful and wealthy, Late Bronze Age civilizations, including New Kingdom Egypt and the Hittite Empire based in what is now Turkey. Extensive networks of material and cultural exchange crisscrossed the eastern Mediterranean during the Mycenaean period, as they had done for centuries before the Mycenaeans even arrived on the scene. The Egyptian pharaohs and the Hittite kings commanded vast armies of infantry and chariots, and advertised their military exploits in official correspondence and on monumental inscriptions and relief sculptures. Even though the most powerful Mycenaean rulers commanded far less territory and far fewer soldiers than their Near Eastern counterparts, they adopted the martial iconography and ethos of their more powerful neighbors. As the study of Mycenaean art and archaeology has revealed, Mycenaean kings and nobles rode into battle on chariots – even though Mycenaean topography is much less suited to chariot warfare than the broad plains of the Near East. They also brandished ornate bronze weapons, and celebrated their heroic prowess with martial artistic motifs and status objects. In light of the Mycenaean elite’s desire to advertise themselves as similar to their neighbors, let us consider briefly how the great powers of the Late Bronze Age waged war, and to what extent the Mycenaeans fought in similar ways.4

New Kingdom Egypt, the wealthy and powerful state along the fertile land watered by the Nile River, still looms large in the modern imagination. The pharaohs were experts at self-promotion, most famously by building the pyramids, but also by advertising themselves and their military exploits on the walls of their temples in both text and image. Ramesses II, better known as Ramesses the Great, praised his own valor to the skies on the temple at Abu Simbel and other sites throughout the country, memorializing Egypt’s battle against the Hittite Empire at Kadesh in 1274 BCE. The Hittites, Egypt’s sparring partner in this first battle for which we have anything close to a complete picture, are much less well-known. Controlling most of what is now ...