why may not a whole estate be thrown into a kind of garden by frequent plantations, that may turn as much to the profit as the pleasure of the owner?... Fields of corn make a pleasant prospect, and if the walks were a little taken care of … if the natural embroidery of the meadows were helped and improved by some small additions of art, and the several rows of hedges set off by trees and flowers … a man might make a pretty landscape of his own possessions.1

Stephen Switzer, in Ichnographia Rustica (1715), reiterated the theme of profit and pleasure, writing that, “By mixing the useful and profitable Parts of Gardening with the pleasurable in the Interior Parts … and Paddocks, obscure Enclosures, etc. in the Outward: My Designs are thereby vastly enlarged and both Profit and Pleasure may be said to be agreeably mix’d together.”2 Switzer drew on the classical poet Horace to define three key aspects of this style of garden design: utile dulci, or the combination of cultivation and pleasure; ingentia rura, taking an expansive view of design, and designing the whole property, not just pleasure gardens distinct from the farm areas; and simplex munditiis, or simplicity and noble elegance.3 These elements combine to describe the ferme ornée in which the recreational portions of a country estate are integrated into the farm’s livestock pastures, hay meadows, and crop fields.

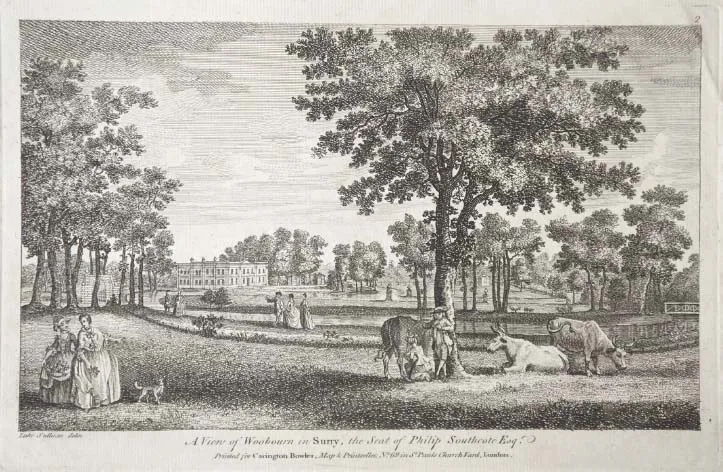

In the ferme ornée, cultivated lands were an integral element of garden design and vice versa. Highly ornamental and lavishly planted linear gardens circumambulated pastures and fields. Designers carefully staged views from the paths of the strolling garden to the farm to create scenes that evoked landscape paintings. Designers and visitors understood these views and the life they represented to be physically restorative and emotionally inspiring. The gardens created bucolic scenes like those painted by Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, whose scenes of idle merriment and joy portrayed shepherds in a pure, idyllic life, separate from the taints of the city, where “all is lovely – all amiable – all is amenity and repose; the calm sunshine of the heart.”4 This painterly approach, of course, masked the labor of the working farm, presenting the agricultural landscape and the work that occurred there as a soothing view to be consumed for pleasure. (Fig 2.1)

2.1

Philip Southcote’s Woburn Farm, after Luke Sullivan, c. 1759. A walk led visitors through the farm where crops, livestock, and labor were displayed and aestheticized.

By the mid-eighteenth century in Britain, this bucolic approach was well established in the “new” garden design, design based on natural forms rather than geometric principles: Batty Langley, in New Principles of Gardening (1728), stated that, “the End and Design of a good Garden is to be both profitable and delightful.”5 By the end of the century, Horace Walpole, in his highly influential Essay On Modern Gardening (1771), described three types of modern, naturalistic gardens: “the garden that connects itself with a park, … the ornamented farm, and … the forest or savage garden.”6 He noted William Kent as the author of the first, and Philip Southcote as the founder of the second, the ferme ornée.

Southcote’s Woburn Farm was well known in its era, and its forms and plantings influenced the design of other British estates. Southcote’s design principles were described in many essays and books, and tourists frequently visited the farm to see the innovative layout and planting scheme.7 And the farm and others like it influenced American as well as British garden design. Woburn Farm was vividly described in Thomas Whatley’s Observations on Modern Gardening (1770), which Thomas Jefferson and John Adams carried with them as they toured British gardens in 1786. The two visited Southcote’s estate, Jefferson noting that, “all are intermixed, the pleasure garden being merely a highly ornamented walk through and round the divisions of the farm and kitchen garden.”8 (Fig 2.2)

2.2

View in the Grounds of Woburn Farm, Charles Stirling, c. 1815. The linear walk staged views of the farm from defined vantage points.

Both Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello and James Madison’s Montpelier have aspects of a ferme ornée. In 1807, Jefferson proposed adding “a winding walk surrounding the lawn before the house, with a narrow border of flowers on each side … the hollows of the walk would give room for oval beds of flowering shrubs.”9 Monticello is laid out with four connected circular drives dividing the plantation into concentric zones of lawn; grove; orchard, vineyard, and vegetable plots; and crop fields, pastures, deer park, and woodlot. The house and lawn sit at the peak of the mountain, looking out over the farm districts below.10

Philip Southcote was part of a group of designers radically changing British garden design in the eighteenth century. Alexander Pope and William Kent “practiced painting in gardening,” with Kent credited for introducing the new “natural taste” in garden design, and Lord Petre “carried it farther than either of them.”11 Southcote was friends with both Pope and Kent, and considered himself a pupil of the eighth Lord Petre, who was one of the finest botanists of his time, with an extraordinary collection of exotic and regional trees, shrubs, and plants,12 many likely from John Bartram’s expeditions in America, which Petre helped to finance.13 Southcote described him as, “a nursery-man … [who] understood the colors of every tree, and always considered how he placed them by one another.”14 From Petre, Southcote developed a horticultural approach to garden design that considered in particular the texture and color of trees and shrubs across the year; Petre’s gardening papers included a list of trees ordered by foliage color, running from weeping willow to sycamore, titled “Shades of Green; deeper & deeper.”15 (Fig 2.3)

2.3

Plan of a grove, Joseph Spence, c. 1760. Spence used a painterly approach in this composition, framing darker evergreen trees with lighter, fine-textured, and flowering trees.

Eighteenth-century English garden design was based in ideas of painterly composition, with a premium on variety, surprise, and delight. Pope neatly summed the aims of the style, “He gains all Ends, who pleasingly confounds, / Surprises, varies, and conceals the bounds.”16 And the author Joseph Spence noted that, “All the beauties of gardening might be comprehended in one word, variety.”17 While William Kent’s version of the English garden drew on the Elysian, Classical paradise imagery of Claude Lorrain, with soft, muted colors, Philip Southcote preferred an Arcadian mode, referencing the pastoral countryside through bright, joyful, floral designs. He “prevailed on Kent to resume flowers in the natural way of gardening,”18 and Southcote’s innovations in the English garden style included the extensive and dense use of colorful and fragrant flowers and the creation of an ornamented peripheral walk.19

At Woburn Farm, Southcote tested and developed the natural style of gardening. Like Kent and Pope, he believed that gardening was a form of painting, and a good garden design should include one or more principle views, composed with consideration “of perspective, prospect, distancing, and attracting,”20 and using clumps of trees, “like the groups in pictures,”21 arranged to draw the eye from the foreground, toward a “distant clump, building, or view.”22 (Fig 2.4) Serpentine paths created ever-changing views; garden follies surprised and delighted the visitor; and a range of exotic and local plants provided an ever-shifting plant palette. ...