![]() Part 1

Part 1

Smart Growth in the Curriculum![]()

1

Using a Studio Course for Provision of Smart Growth Technical Assistance: The University of Maryland's 1999 Community Planning Studio in Perryville, Maryland

James R. Cohen

When a set of initiatives collectively known as “smart growth” was passed by the Maryland legislature in 1997, the acts became the latest in a series of laws, dating back to 1969, that distinguished the state as a leader in land preservation and watershed protection. Spurred largely by concern for the health of the Chesapeake Bay, the legislature had already established laws to purchase open space, farmland, and forests; protect tidal and nontidal wetlands; manage storm-water runoff; regulate development within one thousand feet of the bay and its tidal tributaries; require reforestation and tree planting as a condition of new development; and protect sensitive areas. The smart growth programs contained incentives and planning requirements aimed at curbing sprawl and revitalizing cities and inner suburbs.

To varying degrees most of the laws added planning and regulatory responsibilities to local governments. In early 1999 a faculty member in the University of Maryland’s Urban Studies and Planning Program decided to focus his summer community-planning studio course on the challenges facing one of Maryland’s small jurisdictions as it attempted to comply with its planning mandates and grow in a manner consistent with the state’s smart growth program. The resulting course, What’s Smart Growth for Perryville?, proved to be a rich learning experience for the students and a valuable resource for the town.

This chapter concentrates on how the 1999 summer studio course provided smart growth–related technical assistance to the town of Perryville. It gives brief profiles of the course and Perryville; discusses how the students approached the study; summarizes the major findings and recommendations of the final studio report; critically analyzes the degree to which the report has since been utilized by the town; highlights the students’ reactions to the studio experience; and discusses the lessons learned from the studio.

Overview of the Planning Studio Course and Perryville

The Community Planning Studio is a six-credit “capstone” course for Master of Community Planning (MCP) candidates in the University of Maryland’s Urban Studies and Planning Program (URSP). The one-semester course enables students to apply their knowledge and skills, analyze current, pressing planning issues in a selected community, and produce an oral and a written report containing recommendations for addressing those issues. In essence, the students act as a consulting team for a community client.

In early 1999 several MCP students requested a studio that would enable them to help a rural jurisdiction apply smart growth principles in dealing with new growth. Staff members of the Maryland Department of Planning were contacted for suggestions of possible case-study jurisdictions. James Cohen, the summer studio instructor, also consulted with Uri Avin, principal planner with HNTB, Inc., and member of the planning program’s technical advisory committee, who recommended Perryville as the study site. Avin’s firm had done a study on development opportunities and design options for Perryville’s downtown in 1997 (LDR International 1998), and he thought that a studio report would be an excellent follow-up.

Located at the confluence of the Susquehanna River and the Chesapeake Bay, near the Delaware-Maryland border, Perryville (population 4,500) is the second largest city in Cecil County. During the 1990s the town’s population grew by nearly 50 percent, while the state’s population grew by less than 11 percent. First settled in 1622, for over two centuries Perryville consisted of just a cluster of residences and locally owned businesses along a postal road leading to the Lower Ferry crossing of the Susquehanna River. During the late 1880s the town grew because of its importance as a coach stop at the ferry crossing and as a busy railroad depot. Much of the old town’s freight rail traffic was diverted to roads, however, following construction of major highways (such as State Routes 40 and 7, and U.S. Interstate 95) beginning in the 1940s.

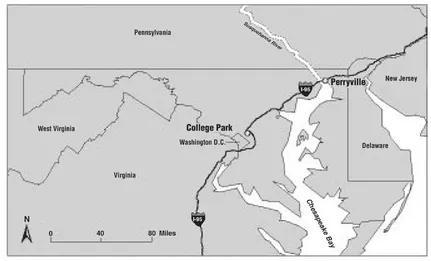

Perryville’s new growth occurred on converted farmland and forests away from the old town center, along Broad and Front Streets, and new, outlying subdivisions were annexed to the town. Further annexations occurred in the late 1980s and early 1990s. By the end of the 1990s the major employer in Perryville was the Veterans Administration hospital, situated on a peninsula just past the old town. Dozens of disabled veterans live in Perryville’s old town in boarding houses that are privately operated. As Map 1.1 indicates, Perryville is approximately eighty miles north of the University of Maryland.

Map 1.1 Perryville, Maryland, in relation to the University of Maryland, College Park Source: Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc. (ESRI) Data and Maps CD (2003).

As with many of Maryland’s rural towns, Perryville does not have a planning staff, yet it is responsible for most of the land use planning and regulation that addresses the state’s environmental and smart growth legislation. About twenty-five smaller jurisdictions on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay rely on the Maryland Department of Planning’s “circuit-rider” planners for technical assistance in implementing their Critical Area land use program (discussed below), but this occasional assistance is constrained by limited state personnel and financial resources. Such limitations can hamper smart growth implementation in smaller jurisdictions, but create conditions suitable for graduate planning programs to offer technical assistance. For the above reasons, Perryville provided a studio opportunity with mutual benefits for the town and the students.

Perryville’s town administrator at the time, Sharon Weygand, was grateful for the offer of planning services and technical assistance. The town commissioners subsequently endorsed the proposed studio. As is done with all URSP studio courses, an advisory committee was assembled comprised of major stakeholders at the local and county levels. Committee members would assist the students by identifying key issues in Perryville and Cecil County and by providing them with background information and planning documents. The nine members of the studio advisory committee included a town commissioner, the chairperson of the town’s planning and zoning committee, the town administrator, the Cecil County planning director, the county’s principal planner, the chairperson of the county economic development committee, two persons working with the Lower Susquehanna Heritage Greenway Project (which had economic and environmental importance to the town), and the Maryland Department of Planning’s circuit-rider planner for Perryville.

After selecting the studio site, organizing the advisory committee, and compiling initial information and documents, the course instructor facilitated some of the student group discussions, acting sometimes as an ambassador between town officials and the students, and serving as occasional chauffeur (to take the eleven students on the 80-minute drive from campus to the town). He also exhorted the students to complete the written report by the end of the twelve-week summer session.

The town did not provide the studio with funding. Class expenses were supported with $600 from the Summer Programs division of the University of Maryland’s Office of Continuing and Extended Education. The funds were used to pay for layout and printing of the final report. In addition, the Summer Programs division set aside $320 of the participating students’ tuition, which was spent for the use of a van from the university’s motor pool to make site visits to Perryville. For its part, the town gave the students the use of the Rogers Tavern, an historic landmark on the shore of the Susquehanna River, as a meeting place. The town also gave the students access to all documents needed for the study. In addition, town-elected officials and other stakeholders were very responsive to students’ requests for interviews.

At a meeting at the beginning of the semester, each member of the advisory committee was given a chance to tell the students what he or she believed were the most compelling planning challenges facing the town. Following are the main issues raised by the committee:

- Perryville’s comprehensive plan had been updated in 1997, prior to the full unveiling of Maryland’s Smart Growth Initiatives; thus the plan needed to be reviewed to determine its consistency with the new initiatives.

- Neither the town’s zoning ordinance nor subdivision regulations had been updated in decades; they were not consistent with either the 1997 plan or Maryland’s 1997 smart growth legislation.

- Perryville does not have an easily recognized town center or even a landmark.

- There was a vacant, one hundred-acre industrial site in Perryville, formerly the location of the Firestone Plastics Company. It was unoccupied, due largely to poor access for trucks. Resident protests stopped a recent proposal to build an incinerator on the site, and the town was exploring other opportunities for the land’s utilization.

- Commercial development in the area is found at the Outlet Mall off Interstate 95, on each side of Route 40, and (in small measure) in Perryville’s old downtown. However, the town does not have a supermarket. Although an estimated 1,200 workers and visitors drive through the old downtown each day to reach the VA hospital, no attempt had been made to capitalize on the potential market created by the hospital-generated trips. Questions also arose as to how to bring the boarding homes for VA patients up to code. Some town commissioners were reluctant to put pressure on the boarding homeowners, but dilapidated properties were thought to undermine the old town’s growth potential.

- The MARC train station in the old downtown was not being utilized for its commercial potential. (The MARC train connects Perryville to Baltimore and Washington.) The station could provide goods and services not only to daily commuters but also to downtown residents. Across from the train station and overlooking the Susquehanna is the historic Rogers Tavern, which was also underutilized. Because the population will increase within and near the old downtown, questions were raised about the kinds of commercial and/or tourism opportunities the town could pursue.

- The Lower Susquehanna Heritage Greenway Project was in its final planning stages and would create a corridor of protected open spaces along the Susquehanna River in Cecil County and neighboring Harford County. With its system of looping walking/biking trails, the greenway will provide recreational opportunities, habitat for rare species, and access to scenic views, historic sites, museums, local festivals, and cultural events. The town was deliberating the ways in which it could benefit from the greenway’s economic development potential.

How the Students Approached the Studio Report

After the first meeting with the advisory committee and during the next twelve weeks, the students completed the following tasks:

- determined which of the above issues they could deal with in the given timeframe;

- organized their research agenda;

- read relevant literature, including state legislation, smart growth Web sites, and local, county, and state planning documents;

- collected data, conducted interviews with advisory committee members and other individuals with information and perspectives relevant to the studio topic;

- attended meetings of the Town Commission and the Planning and Zoning Commission;

- conducted extensive site surveys; and

- investigated potential sources of funding and technical assistance for implementing smart growth in the town.

The students gave an oral presentation to the advisory committee in September 1999, along with a written report. The written portion was intended to be a working document—something the town could use to manage growth in a way that is consistent with the major state legislation, including the Maryland Smart Growth Initiatives.

To guide them in their work, the students defined smart growth in two ways. One definition referred to local land use procedures and outcomes that are either mandated or encouraged via incentives. The mandates and incentives are established by four laws, collectively labeled as Smart Growth, which have been passed by the Maryland legislature since 1984 to prevent sprawl and/or protect environmentally sensitive areas. The second definition consisted of a set of general principles expressed in such Maryland legislation and in other local, state, and national antisprawl initiatives. These general principles were denoted as smart growth (lowercase s and g).

The first Maryland law that the students included under Smart Growth was the 1984 Critical Area Act, designed to improve water quality, protect habitat, and manage growth within a zone one thousand feet from the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal tributaries. The act mandates that jurisdictions inventory their Critical Area land into three zones, depending on the intensity of the actual land use. A one hundred–foot buffer from the shoreline is required for all new development, with exemptions for certain types of water-dependent uses. The local governments must then implement land regulations and performance standards specific to each of the zones, subject to oversight by a state commission. Because of Perryville’s location, much of the town’s land is subject to Critical Area Act requirements.

The Forest Conservation Act of 1991 constituted the second Smart Growth law under the students’ classification. That act requires developers to replace some of the forests cleared for building and to plant trees on development sites that have few or no trees. Local governments are responsible for implementing, monitoring, and enforcing the act.

The third Smart Growth Maryland law, the 1992 Economic Growth, Resource Protection and Planning Act, is meant to facilitate economic growth and development that is well planned, efficiently serviced, and environmentally sound. The legislation required jurisdictions, by 1997, to incorporate the following seven visions into their comprehensive plans: (1) development is concentrated in suitable areas; (2) sensitive areas are protected; (3) growth in rural areas is directed to existing population centers, and resource areas are protected; (4) stewardship of the Chesapeake Bay and the land is a universal ethic; (5) conserving resources, including reducing resource consumption, is practiced; (6) to assure the achievement of the first five visions, above, economic growth is encouraged and regulatory mechanisms are streamlined; and (7) funding mechanisms are addressed to achieve these visions.

Under the 1992 act, new “sensitive areas” were to be included in plan updates. Each jurisdiction was allowed to define and determine the level of protection for steep slopes, streams and their buffers, the one hundred–year floodplain, and habitats of endangered species. Once the plan with the new sensitive areas element was adopted, the law required that zoning and subdivision regulations become consistent with the plan. Local planning commissions must review and, if necessary, amend their plans every six years.

Certainly the most nationally recognized of the four Maryland laws that the studio team defined as Smart Growth was the bundle of five programs passed in 1997 under the leadership of former g...